Written by Richard Covington

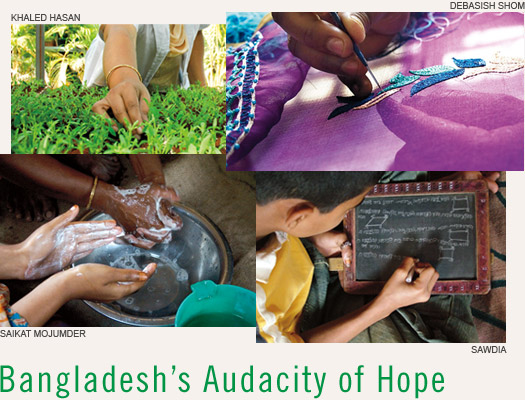

Photographed by students at

Pathshala, the South Asian

Institute of Photography

nside a metal-roofed bamboo shed, teenage girls noisily amuse themselves playing chess, pool and board games. The girls are Marma, one of 11 ethnic and linguistic minorities who have inhabited the southeastern district

of Bangladesh known as the Chittagong Hill Tracts for centuries.

The twice-weekly meetings at this teen center, near the town of Bandarban, 30 kilometers (19 mi) west of the Burmese border, are supervised by Numei Prue, 26. Calling a temporary halt to the games, she leads the group in a love song, accompanying the choir on harmonium. Later, she directs a discussion

that ranges from the business of running a tailor shop or a beauty parlor to the dangers of HIV/AIDS and the risks of early marriage.

nside a metal-roofed bamboo shed, teenage girls noisily amuse themselves playing chess, pool and board games. The girls are Marma, one of 11 ethnic and linguistic minorities who have inhabited the southeastern district

of Bangladesh known as the Chittagong Hill Tracts for centuries.

The twice-weekly meetings at this teen center, near the town of Bandarban, 30 kilometers (19 mi) west of the Burmese border, are supervised by Numei Prue, 26. Calling a temporary halt to the games, she leads the group in a love song, accompanying the choir on harmonium. Later, she directs a discussion

that ranges from the business of running a tailor shop or a beauty parlor to the dangers of HIV/AIDS and the risks of early marriage.

“This center is a safe haven where the girls meet together to sing, dance, play games and talk about their futures,” she explains outside in a dirt courtyard shaded from the harsh January sunlight by an enormous

rain tree. “It’s a lifesaver for all of them; otherwise they’re stuck at home.” This scene is repeated time and again all across

Bangladesh, where there are more than 8700 such centers, some of which give training in handicrafts as well as computer

literacy, photography, lab research and even journalism.

This national network of centers for adolescent girls is one of the many brainchildren of 73-year-old Fazle Hasan Abed, who in 1972 founded BRAC, now the largest non-governmental

organization (NGO) in the developing world. Providing

microfinance, health care and free schools to 110 million

of the poorest among Bangladesh’s 155 million people, BRAC employs some 121,000 staff (including around 64,000 teachers) and relies as well on countless volunteers and part-time workers. Formerly known as the Bangladesh

Rural Advancement Committee but now officially called “BRAC,” the organization is present in virtually every village, town and urban slum of this 38-year-old democracy, one of the planet’s most densely populated and impoverished countries, where one out of three people subsists on less than $1 a day.

One of BRAC’s most notable early successes

was its house-to-house campaign to teach young mothers to administer oral rehydration solution to treat life-threatening childhood diarrhea. Together with an immunization drive in partnership with the government, the campaign reduced infant mortality in Bangladesh dramatically: from one in four children—

25 percent—dying before age five in 1979, to around seven percent today. And the greater survival rate, along with greater availability of contraceptives,

has helped reduce the number of children in the average Bangladeshi family from seven 30 years ago to 2.7 today. Additionally, nearly 70,000 health-care volunteers—mostly women drawn from 293,000 groups of microfinance borrowers—are helping cure tuberculosis (TB) and malaria. Now the quietly forceful

Abed, a former oil executive with a fondness for quoting both Shakespeare and Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore, is expanding operations beyond Bangladesh

into Afghanistan, Uganda, Southern Sudan, Tanzania, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Sierra Leone and Liberia.

While less well-known than Grameen

Bank, the microcredit empire founded by Nobel Peace Prize-winner Muhammad Yunus, BRAC casts a wider net. In addition to its antipoverty, health and education programs,

BRAC’s operations include a commercial

bank, a university, a plant-tissue culture laboratory, seed-processing centers, dairies, chicken hatcheries, a poultry-feed factory, silk production and a chain of retail stores funding local artisans, as well as management

of around $4.7 billion in microfinance loans to 8.5 million women.

Last October, Abed was awarded the $1.5 million Conrad N. Hilton Foundation Humanitarian

Prize, the world’s richest humanitarian award, and in 2007, the Clinton Global Initiative,

founded in 2005 by former US President

Bill Clinton, presented Abed with its first Global Citizen Award. In conferring the Clinton prize, Kenyan activist and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Wangari Maathai noted that Abed founded BRAC “on the belief that poverty must be tackled from a holistic viewpoint,

transitioning individuals from being aid recipients to becoming empowered citizens

in control of their own destinies.”

In 2004, Microsoft founder Bill Gates presented

BRAC with the $1-million Gates Award for Global Health. “BRAC has done what few others have—they have achieved success on a massive scale, bringing lifesaving health programs

to millions of the world’s poorest people,”

Gates said at the ceremony.

Like all of BRAC’s myriad projects, the teen centers were established to meet a pressing need. “We were afraid that the girls who had gone to our primary schools might lose the literacy and self-respect they had earned and get pressured into early marriages,” Abed explains in his Dhaka office. “Everybody is telling adolescent girls to be subservient to men and boys, that they can’t go out on their own. We felt that this process needs to be attacked.” A reserved, avuncular figure with snowy white hair and wire-rimmed glasses, the generally affable Abed raises his voice slightly to emphasize his passion for the subject. Behind his customary smile is the persuasive pragmatist who takes obstacles in his stride and calmly overcomes them, one by one, by refusing to accept “no” for an answer.

“We encountered some resistance from parents bent on marrying off their daughters,” he continues, “but most parents realize that our free schools teach their children many things that government schools do not, and that the centers give the older girls further education, job skills and self-worth in a place that is all their own.” Both parents and daughters

see the centers as refuges from those men and boys who might look upon unmarried women outside their homes as fair game for aggression or even rape.

The fact that the female adolescent centers—

along with microfinance groups, health volunteers treating TB and malaria, primary schools, community organizations, legal-services clinics and grants providing cows to the poorest of the poor—are available not only to the majority Bengali population, but also to remote minorities like the Marma, Chakma, Garo and other “hill tribes” is further testimony

to the inclusive sweep of BRAC’s humanitarian

goals. During a little more than two weeks of visiting a wide range of projects, I witnessed firsthand how this mission gets in the blood, inspiring dignity and self-reliance in people who thought they had been forgotten—yet without making them dependent. “We can give the poor access to resources, like through microfinance,” notes Abed. “But they have to pay for it—either in labor or money. Ultimately, the poor have to change their own condition.”

Take Momena, a 60-year-old widow who, like many villagers, goes by only one

name. Today she is a beneficiary of BRAC’s Ultra Poor Programme, founded in 2007. A year ago, she was a beggar, scraping by on less than 50 taka (85¢) a day in a rural settlement near Mymensingh, 150 kilometers

(90 mi) north of the capital. Too poor to qualify for even the minimum microcredit loan of 4000 taka ($68), Momena received instead two cows, which sleep in part of her small hovel. Trained by BRAC instructors how to care for them, she now sells the milk from one and is fattening the other to sell for slaughter. With the proceeds, she plans

to buy a small plot of land for rice cultivation

and hire a laborer to help her farm it.

Take Momena, a 60-year-old widow who, like many villagers, goes by only one

name. Today she is a beneficiary of BRAC’s Ultra Poor Programme, founded in 2007. A year ago, she was a beggar, scraping by on less than 50 taka (85¢) a day in a rural settlement near Mymensingh, 150 kilometers

(90 mi) north of the capital. Too poor to qualify for even the minimum microcredit loan of 4000 taka ($68), Momena received instead two cows, which sleep in part of her small hovel. Trained by BRAC instructors how to care for them, she now sells the milk from one and is fattening the other to sell for slaughter. With the proceeds, she plans

to buy a small plot of land for rice cultivation

and hire a laborer to help her farm it.

Perhaps the most successful aspect of BRAC’s approach to poverty alleviation is that projects are driven largely by economic incentives. Women take small loans to start grocery shops or garment-manufacturing, cattle-raising and other ventures that, with hard work, ultimately earn profits, enabling the women to take larger loans and expand their businesses. Health “volunteers” aren’t literally that: They earn money by fighting TB and malaria, and also by selling medicines

at a small markup. The most radical aspect of BRAC, however, is what economists would call vertical integration: BRAC-run enterprises stretch from village fields to town markets and urban stores, plowing profits from dairy, poultry, silk, textile and handicraft productions, run by the poor, back into BRAC programs.

From individuals like Momena to entire communities, BRAC is remaking Bangladeshi society, encouraging low-income citizens to take part in—even to take charge of—political processes that have often left them out. For example, in a village courtyard near Mymensingh, it was heartening and somewhat

astonishing to see some 200 farmers, laborers and housewives assemble beneath jackfruit trees and date palms for a bimonthly BRAC-sponsored polli shomaj (“rural society”) meeting, at which government officials spelled out details of school stipends, employment

programs, wheat allotments and marriage laws.

“These community pressure groups ensure that the poor get the government money, resources and legal help they’re entitled to,” points out Zarina Nahar Kabir, director of BRAC’s social-development program.

“We try to help people understand that democracy is something you have to practice to make a reality.”

What I observed in Mymensingh was certainly

democracy in action, with one woman from the audience vigorously complaining to the marriage registrar over the illegal (but still widespread) custom of demanding, even extorting, dowries from brides’ families.

Apart from fielding more than 12,000 polli shomaj groups, BRAC also conducts nationwide classes in human rights and basic legal rights. It also trains hundreds of paralegal

advisors, so-called barefoot lawyers who handle property and family disputes, as well as more serious cases.

The organization’s community-development

drive even extends into show business.

With 400 amateur acting troupes staging some 1600 performances every month, BRAC literally dramatizes, village by village, the social, familial and economic conflicts that villagers face daily. For many rural inhabitants, BRAC’s popular theater, presented at their doorstep, is the only live entertainment in the village all year.

One evening performance I attended brought a thousand villagers to congregate in the dark around a makeshift outdoor stage. With banging drum, clanging cymbals and a high-pitched vocal to set the scene, the attention-grabbing introduction gave way to a cautionary tale about an evil factory manager

cheating his boss, exploiting his workers and even trying to seduce the teenage daughter

of a poor family. At critical junctures in the plot, the actors would pause and ask the audience

what should happen next. At the end, the audience clamored for the manager to be fired, but not before he was compelled to beg forgiveness of all the people he’d wronged. I was amazed that all the dialogue was largely improvised by non-professional, volunteer actors.

“The stories [for the dramas] are collected

from the local community, and cover everything from workers’ rights to forced marriages, HIV/AIDS, sanitation, even bird flu,” Kabir explains. “We try to end with a positive message.”

BRAC’s positive messages began 37 years ago. That’s when Abed first set up operations in the northeastern Sylhet district, near where he’d been born in 1936 in what was then the Bengal region of British India. (Following the partition of 1947, the district became part of East Pakistan, and then part of Bangladesh when that country won its independence in 1971.) Abed had come back from London in 1972 to help refugees, who were returning by the millions from India to their war-torn homeland.

Although Abed ventures into rural villages only infrequently

these days, he’s in his element when he does. He remains totally approachable, sitting on the ground to listen to hardscrabble residents’ observations

and complaints. His frank equanimity sets even the humblest audiences at ease. “Every time I go into the field and see people operating under difficult circumstances, it reinforces my commitment,” he maintains.

The son of a prosperous landowner and government

official, Abed grew up in a house full of servants. “My mother was a very pious and kindhearted person, so we continuously had poor people coming through our home, getting food and small loans,” he recalls from his top-floor office of BRAC’s 21-story Dhaka headquarters.

Behind him hang paintings by noted Bangladeshi artist Quamrul Hassan. (A knowledgeable art enthusiast, Abed faithfully sets aside time for museum visits on his trips abroad.)

After going to university in Dhaka and studying naval architecture in Glasgow, he migrated to London to become an accountant. Working for commercial firms, Abed was leading the comfortable life of a well-to-do expatriate.

After a dozen years in the British capital, he returned to Bangladesh as treasurer, and later head of finance, for Shell Oil in the southern port city of Chittagong.

Two years later, in November 1970, the Bhola cyclone, the deadliest in history, slammed into the area, killing an estimated 500,000 people and leaving many more destitute.

Abed joined friends volunteering to work in cyclone relief and was transformed by the experience. “I realized how fragile existence was for the poor, the ones who were hardest hit by the cyclone, and that I needed to start doing something more significant with my life,” he recalls.

Part of his new resolve also took on a political dimension: going back to London to rally support for Bangladesh’s liberation movement. “I lobbied members of Parliament, did television programs about Bangladesh being torn apart by racial murders and about the refugees streaming out of the country to escape the violence,” he says. “Ultimately, we did get support from the international community, first from India, then from other countries.”

After a nine-month war in which hundreds of thousands died (some say millions—the total is widely disputed), newly independent Bangladesh found itself at peace in December 1971, but with an economy in ruins—“an international basket case,” in the cynical words of then US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, whose boss, President Richard Nixon, had backed Pakistan.

After the war, Abed took a non-partisan tack, selling his London flat and committing his own future to the new country. “After independence, I had no hesitation about going back to start relief work for refugees trekking home from India,” he recalls. Using the $17,000 proceeds from his flat, Abed and a few friends soon focused on the needs of the poor with a new organization they dubbed the Bangladesh Rehabilitation Assistance

Committee, which they changed the next year to “Rural Advancement.”

The most crucial early goal, Abed explains, was simply to keep children alive. With the advice of diarrhea specialists, Abed devised a scheme, controversial at the time, to empower poor mothers to administer oral saline solution to their own youngsters. It was controversial because it relied not on doctors and clinics but on overwhelmingly illiterate villagers. The simple technique of mixing water, salt and sugar was taught door-to-door in every village, however remote, by BRAC instructors. It took years to get started and a decade to finish, but BRAC workers reached more than 12 million households, each worker earning $40 a month, on average, for carrying out this lifesaving, incentive-based health campaign. “Once we had gone to virtually every household in the country, Bangladesh became our backyard,” Abed observes. “Lowering

child mortality—knowing that more than 280,000 children are alive today because of BRAC—has been one of the biggest satisfactions

of my entire career.”

Starting in 1974, BRAC organized microfinance

groups to build the economic, social and familialclout of women who would not qualify for conventional bank loans. In Korail, an

urbanslumof 30,000 inhabitants on alake across theroad from BRAC’s headquarters, Iattendedaweeklymeetingof a BRAC microfinance group—of which there are now 293,000 nationwide.

After navigating narrow lanes with open sewers, my BRAC guide and translator

Fariduzzaman Rana led me into one of the thousands of corrugated metal shacks. Inside the one-room home of the group’s leader, two dozen women sat on the floor beneath walls papered with newsprint. One by one, they handed over to the female BRAC coordinator installment payments on their 40-week loans. She jotted down each amount in a notebook.

Dressed in a pink-and-green

sari, one of the loan recipients, Nurjahan, told me she has spent 18 of her 33 years in Korail. Like many residents, she fled here with her family after flooding and river erosion

destroyed their home; hers was in the southern district

of Barisal. Taking a loan of 20,000 taka ($340) a few years ago, she started a business sewing clothes. Now she earns enough to employ two assistants and put aside 40 taka a week (68¢) in savings.

Other women have invested in small grocery shops or in handicraft,

weaving and tailoring businesses.

In the countryside, in addition to such activities, borrowers

also buy cows, poultry and modest plots of land to cultivate

rice and other crops.

In this group, the loan repayment rate is 100 percent; nation-wide, repayments run a remarkable 99.35 percent. “If anyone has difficulty

making a payment, other members chip in,” says Nurjahan.

“We felt that poor women are more disciplined than men about repayments,” Abed later explains. “And it is a way to give them more control over decisions within the family,” he adds. The organization

does, however, make substantial loans of 50,000 to 500,000 taka ($850– $8500) to men with established small-and medium-sized enterprises, many in the garment and furniture industries.

After the meeting, Rana took me to BRAC’s obstetric clinic. To get there, we passed carpentry and metal-working shops, crews of men chopping up scrap wood for cooking fires and ramshackle tea

stalls with audiences glued to Bengali action

films that crackled over aged television sets.

The clinic—the so-called “birthing hut”—

is a clean, well-lit, cement-block building

with an office and waiting room in front and a delivery room in back. Basic though it is, the two-year-old center is one of 79 located throughout the slums of Dhaka, part of BRAC’s program to improve maternal and neo-natal health, which is powered by a $5.5-million grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

“It’s far safer than traditional home birth,” maintains program manager Sujatada Biswas. “Many expectant mothers in Korail are very afraid of hospitals, so now around 80 percent of them come here, but if there are complications, we refer them to private clinics or government hospitals.”

Like the microcredit programs, health care—whether for pregnant women or TB or malaria patients—is primed by financial incentives. BRAC “volunteers” earn 30 taka (51¢) for each referral to the clinic, and another 200 taka ($3.40) for helping “their” referred woman keep coming to the clinic through the birth of her child. During the pregnancy, a full-time staff health worker also makes home visits to explain to the family what to expect and what to do in case of problems. After the baby is born, the health worker outlines such common ailments

as diarrhea, dysentery and worms with the help of simple drawings depicting babies with various symptoms, together with appropriate medicines. Then, over the next six weeks, the BRAC workers make more home visits. “We’ve had eight to 12 births per month since we opened in early 2007 and are fortunate and very grateful that we have not lost any babies or any mothers,” Biswas asserts.

Abed’s commitment to saving mothers and their newborns is a deeply personal one: His first wife, Ayesha, died in childbirth in 1981, when his son Shameran was born; the boy is now an editor for a Dhaka newspaper.

“I thought at the time, ‘My God, if my wife can die in a Dhaka hospital, it must be so much riskier for the poorest women having

difficult childbirths in rural areas without

any hospitals, without any support,’” he explains during our interview. “That’s what drives me still to cut down on maternal mortality.”

At present, some 320 Bangladeshi women die for every 100,000 births, around 13,000 each year nationwide—more than 12 times the rate in industrialized countries.

“Right now, the program is in a pilot phase, targeting 30 million people,” he explains. “But once we test it, make it more effective and efficient, then we will scale it up to cover the entire country.” This procedure—testing a pilot program, correcting mistakes, making

improvements, then scaling it up— has become the tried-and-true BRAC way of doing things.

Although the self-effacing former accountant is characteristically the first to credit others for ideas, he indeed originated

many of BRAC’s initiatives. About 15 years ago, Abed recalls, he had an eye-opening conversation with a woman in a village in northwest Bangladesh

who had borrowed 6000 taka ($102) to buy a dairy cow. When he asked if she were pleased with her milk profits, he was shocked to hear that she had very few buyers in the village and had to sacrifice the milk for a pittance, a mere seven taka per liter (11¢ a quart).

“All of a sudden, I realized that if we could collect milk from these villages, we could sell it in Dhaka for four times as much,” he explains. “That’s when I got the idea of creating

chilling plants in remote areas.” Refrigerated

trucks would then bring the milk to Dhaka, where BRAC factories would pasteurize it and produce

butter, yogurt and other dairy products. After testing the idea on a limited basis, BRAC scaled it up into a nationwide

grid of chilling stations. “We more than double the dairy farmers’ incomes—and we also make money in the milk business, to plow the profits back into other programs,” Abed notes with evident satisfaction.

Conjuring up imaginative solutions to seemingly intractable problems, both in the private and public sectors, has become

one of BRAC’s great strengths. The organization

frequently steps into the void left by a lack of private enterprise on the one hand and inadequate, poorly managed

public services on the other.

Abed has assiduously kept politics at arm’s length, and he has repeatedly turned down ministerial posts to avoid getting involved in factionalism. He acknowledges that the Bangladesh government

may be envious, at times, of the organization’s success in attracting foreign

donors, who pour more than $120 million into BRAC’s $485 million annual

budget. “There is some tension,” he admits. “When we get large sums from donors, the government thinks the money should have come to them.” But donors are won over by BRAC’s transparency and no-nonsense

corporate approach that combines internal

expense monitors and outside auditors.

Health care is a prime example of BRAC’s critical role in supplementing government facilities and personnel. With the country’s annual spending on health running an abysmal

$12 per capita, the organization’s network

of close to 70,000 health volunteers literally makes the difference between life, chronic illness and death for millions of Bangladeshis.

Ask Golam Mostafa. The 45-year-old field hand, who lives in a village near Mymensingh,

is recuperating from TB thanks to BRAC community health volunteer Josna Rani Sarkar. I met Mostafa and Sarkar in the village courtyard under coconut palms and towering teak trees; in the distance stretched refulgent yellow mustard fields and a patchwork

of rice paddies in varying hues of green alternating with earthen brown plots awaiting planting. Sarkar, a 28-year-old housewife, was garbed in a stylish lavender salwar kameez, the loose-fitting pants-and-tunic outfit popular in Bangladesh, and was wearing a gold nose ring.

Four months ago, on her regular rounds to the 160 households she calls on each month, Sarkar was alarmed by Mostafa’s persistent cough, and she asked him for a sputum sample

for testing. When BRAC’s lab confirmed TB, she started treatment—but only after the field hand had given her a 250-taka deposit ($4.25), to be returned in full after he completed the six-month regimen. It’s an incentive to finish treatment, she explains, because some patients stop taking medicine when they start feeling better, before the six months are up. Not only does this potentially fatal mistake greatly heighten the risk of relapse, it also encourages the development of drug-resistant strains of TB. For her part, Sarkar earns 150 taka ($2.55) for each patient she identifies and cures. Now, every morning at eight, Mostafa stops by her house for his daily dose, supplied free by the government. Sarkar dutifully marks it down in her patient log. In two more months, he should be cured.

Community health volunteers like Sarkar receive two weeks’ training to identify TB, malaria and intestinal and respiratory ailments,

as well as pregnancies and dental and vision problems. If necessary, they refer more serious cases to doctors. The volunteers make their rounds with portable pharmacies packed with oral saline solution, scabies and worm treatments, antihistamine syrup, vitamins, iron tablets, condoms and birth-control pills. (By offering cheap contraceptives, trusted volunteers have played a role in helping break widespread taboos around birth control.) BRAC sells the medicines and health products to the volunteers, who resell at a small markup to villagers who rarely if ever see a doctor.

“Curing TB patients like Mostafa motivates people to come to me with their health problems,”

Sarkar says proudly. “I’ve gained a status as a healer in the community that I never had before.” Her newfound ambition is to train as a full-time nurse.

Nurturing ambition is also a key function of BRAC’s 63,000 pre-primary and primary schools—one of the largest private

education systems in the world. It reaches 1.8 million,

or around 10 percent, of the country’s poorest children between the

ages of four and 14. BRAC’s free schools are meant for pupils who have never attended school and for dropouts, usually kids who cannot

afford government school fees or who found government schools too boring, or both.

Talking with students in the three elementary schools I visited, I was impressed by how high they set their career aims, at their own “audacity of hope”—though the fact that they are in school at all is an accomplishment. “There is a sizable opportunity cost for poor parents to send their children to school,” observes BRAC education director Safiqul Islam. “They’re losing the income their children

could have made working or begging,

so school can be a painful sacrifice for the whole family.”

Rouma, a bright-eyed 11-year-old girl dressed in an embroidered purple salwar kameez, aspires to become a journalist. She

has spent part of every week discussing current

events with her third-grade teacher and 31 classmates in a one-room brick schoolhouse

near Manikganj, 65 kilometers (40 mi) northwest of Dhaka. Her father is a rice farmer; her mother takes care of the family cow. “I want to become a journalist because they get to travel to interesting places around the world,” says Rouma, who has yet to travel outside her village.

A classmate wants to become a judge to try criminals: Like most of the students, she’s been a horrified witness to local versions

of mob justice. Another classmate,

10-year-old

Shopna, dreams

of following in

the footsteps of Salma Akhter, a former BRAC student

who won a national talent-search competition and who is now a Bangla pop star. Shopna’s father sells puffed-rice balls in the market; her mother washes dishes there.

Drawings and stories, samples of the students’ efforts in art and creative writing, decorate the school’s walls. The layout of the classroom near Manikganj is replicated in BRAC schools across the country: Pupils sit in a U-formation

on a burlap-covered floor; stacked in front of them are their books, a small slate and a can containing chalk, counting sticks and pencils.

In addition to a kid-friendly curriculum of Bengali, English, math, science, hygiene and environmental and social studies devised

by BRAC staff to prompt students to ask questions and volunteer opinions, the pupils devote at least 20 minutes each day to singing,

dancing and learning games. In one exercise, they stand up around the walls and clap, as each one randomly calls out the English name of a different country. If any child repeats a country name, the drill starts again from the beginning. The same clapping technique helps them memorize the names of flowers, birds and animals, too. At the end of my visit to the Manikganj classroom, Shopna, the singing hopeful, led the group in an enthusiastic, slightly off-key but nonetheless moving rendition of “We Shall Overcome.”

Familiarizing pupils with current events, fostering imaginative writing, singing, dancing,

performing and learning contests are all features that distinguish BRAC classes from government schools, which are characterized

by rigid discipline and rote memorization.

As a result, the dropout rate for BRAC primary schools is under five percent, compared

to a disheartening 50 percent for government

schools.

“Our kids take a real joy in learning,” declares

Islam. “They’re able to go home and challenge their uncles to name 30 species of birds, like they can. This gives the students huge self-confidence.

“For girls, it’s a place where they find they are equal to boys, unlike their homes, where the father usually dominates,” he continues. “At school, the girls can be leaders.” In fact, 70 percent of the students are girls, a forward-thinking strategy aimed at aggressively

boosting the country’s dismal female literacy rate of 31 percent. Parents are more likely to send their daughters to nearby BRAC schools than a longer distance to a government

school; they also feel their children are safer with BRAC’s married women teachers.

“Another dream I have is to create a top-level boarding school for the brightest one percent of our poor students, say 3000 kids, and give them a world-class education that would open the door for them to go to the best universities,” Abed proposes. “We’re now working on raising donor money for this project.”

Elsewhere, at BRAC’s biotechnology labs in Gazipur, a few kilometers north of Dhaka, researchers are developing disease-resistant strains of potatoes, strawberries, bananas and orchids that produce up to 20 percent higher yields than conventional varieties. Nearby, another lab is perfecting salt-tolerant and flood-resistant rice, as well as seeds designed to withstand

the protracted and increasingly unpredictable droughts in the country’s dry northwest.

Recently, BRAC set up a climate-change adaptation program to work with communities

coping with rising sea levels, floods and cyclones, and is working on improving disaster preparedness and early-warning systems. “But,” warns Abed, “global warming will create havoc in our country

unless we can send more people abroad as emigrants.”

Never one to let a crisis go to waste, the pragmatic humanitarian has a plan—one that, as usual, charts a course far into the future. Taking a puff of the Irish tobacco in his Turkish meerschaum pipe, Abed opens a folder on his desk to show me an agreement signed only a few hours earlier with officials from Ryukyu University in Okinawa for an exchange of Bangladeshi and Japanese students

and researchers. “Japan is rapidly losing

population, so our proposal is to create Japanese-speaking Bangladeshi entrepreneurs

who will eventually send workers to Japan,” he explains. “We could do the same for Korea, Spain, Italy and other countries that are facing aging societies—or even thinly populated places like Namibia,” he adds, calmly taking another puff.

It’s a breathtakingly bold vision. Coming from anyone less down-to-earth than Abed, it might seem quixotic. “It would take decades and could never be sufficient by itself to solve the question of where to settle our booming

population,” he admits, “but as a start, why not?”

Why not, indeed? After

all, a generation or so ago, the very existence of an organization

like BRAC would have sounded far-fetched. Today, however, this improbable, indispensable

force for social change —vastly bettering the lives of 115 million of the poorest people in Bangladesh and beyond—is an undeniable reality, and it is only reasonable to expect it to continue

working wonders.

|

Paris-based author Richard Covington writes about culture, history and science for Smithsonian, The International

Herald Tribune, U.S. News & World Report and The Sunday Times of London. His e-mail is richardpeacecovington@gmail.com. |

About the Photographers

Each photographer credited in this article is an advanced student at Pathshala, the South Asian Institute of Photography in Dhaka. The photos published here and in the print edition were made in a magazine-photography workshop led by Saudi Aramco World Managing Editor Dick Doughty and photographer Amin Aminuzzaman

of the Drik picture agency (www.drik.net), in conjunction with Chobi Mela V International

Festival of Photography, January 24–February 20, in Dhaka (www.chobimela.org). You can contact photographers individually through www.facebook.com. |