To do that, early this March the Abu Dhabi International Book Fair (adibf) hosted some 840 exhibitors—mostly publishers—from 63 countries in the Emirate’s glassy new convention center. Over the fair’s six days,more than a quarter-million visitors—many of them whole families—sought out novels, cookbooks, reference books and  more—mostly in Arabic—and they met and heard dozens of writers and poets read and speak.The publishers, however, were there to do more than listen: Here was a chance to attend seminars on copyright, check out the competition, negotiate translations and distribution licensing, and do the deals that make theirs an increasingly global business.

more—mostly in Arabic—and they met and heard dozens of writers and poets read and speak.The publishers, however, were there to do more than listen: Here was a chance to attend seminars on copyright, check out the competition, negotiate translations and distribution licensing, and do the deals that make theirs an increasingly global business.

Historically, the Arabian Gulf region has long been a crossroads, says Monika Krauss, the general manager of the fair. While other Arab countries, Europe and the Americas are today one part of the international conversation, there are other countries to the east. “We are on the doorstep of India,” she says, highlighting the publishers and authors from the subcontinent who occupied a section of booths, and the full day of readings by Indian authors and poets. Bipin Shah, director of the art-book publisher Mapin Publishing in Ahmedabad, sitting among his beautifully illustrated books on Indian art, calls the fair “a good place for networking and for translations. Also, there is a real potential to sell to libraries here,” due to expanding education in the region. With new museums opening, too, he says, it’s “an ideal place” for a publisher of art books. “The pace here is a bit slower, meaning you can get work done and actually talk with colleagues. It opens up opportunities you don’t get at Frankfurt.”

Historically, the Arabian Gulf region has long been a crossroads, says Monika Krauss, the general manager of the fair. While other Arab countries, Europe and the Americas are today one part of the international conversation, there are other countries to the east. “We are on the doorstep of India,” she says, highlighting the publishers and authors from the subcontinent who occupied a section of booths, and the full day of readings by Indian authors and poets. Bipin Shah, director of the art-book publisher Mapin Publishing in Ahmedabad, sitting among his beautifully illustrated books on Indian art, calls the fair “a good place for networking and for translations. Also, there is a real potential to sell to libraries here,” due to expanding education in the region. With new museums opening, too, he says, it’s “an ideal place” for a publisher of art books. “The pace here is a bit slower, meaning you can get work done and actually talk with colleagues. It opens up opportunities you don’t get at Frankfurt.”

|

| Far left: The fair is “a gateway to the region's emerging publishing industry,” says Jumaa Al Qubaisi, director. Center and right: Monika Krauss, adibf general manager; Ali Bin Tamim, director of Kalima, Abu Dhabi’s leading translation agency. |

Iradj Bagherzade, owner of the London-based publishing house I.B.Tauris, one of the world’s largest publishers to specialize in books on the Middle East in English, credits the adibf—though it’s only four years old in its current form—with “driving more worldwide interest toward Arab literature,” but, he cautions, “It’s still early to determine how effective this will be. A hard reality is that translations from Arabic are expensive to produce and edit.”

Adding to the fair’s rising prominence are its two major prizes, the International Arabic Prize for Fiction (sometimes called “the Arab Booker” because of its support by the London-based Man Booker Prize, the world’s most prestigious fiction award) and the Shaykh Zayed Book Award. Only three years old, the “Arab Booker” is awarded annually to a work of fiction in Arabic with the aim of encouraging its translation, and translation of Arabic literature in general, into other languages. Selected from a short list of six nominees, the winning novel is announced on the first day of the fair. The result is “buzz” about the winner—and about Arabic fiction. “It’s nice to have an award like the Arab Booker,” says Sherif Ismail Bakr, publisher of al-Arabi Publishing and Distribution in Egypt. “We’re seeing more attention from European publishers for Arabic literature. Literary agents, for example, are more eager to sign up Arab authors as clients than they used to be.” The first two prizes, in 2008 and 2009, went to Egyptian novelists; this year, the prize was won

by Saudi author Abdo Khal for his novel Tarmi

bi-Sharar or, in English, Spewing Sparks As Big

As Castles.

Adding to the fair’s rising prominence are its two major prizes, the International Arabic Prize for Fiction (sometimes called “the Arab Booker” because of its support by the London-based Man Booker Prize, the world’s most prestigious fiction award) and the Shaykh Zayed Book Award. Only three years old, the “Arab Booker” is awarded annually to a work of fiction in Arabic with the aim of encouraging its translation, and translation of Arabic literature in general, into other languages. Selected from a short list of six nominees, the winning novel is announced on the first day of the fair. The result is “buzz” about the winner—and about Arabic fiction. “It’s nice to have an award like the Arab Booker,” says Sherif Ismail Bakr, publisher of al-Arabi Publishing and Distribution in Egypt. “We’re seeing more attention from European publishers for Arabic literature. Literary agents, for example, are more eager to sign up Arab authors as clients than they used to be.” The first two prizes, in 2008 and 2009, went to Egyptian novelists; this year, the prize was won

by Saudi author Abdo Khal for his novel Tarmi

bi-Sharar or, in English, Spewing Sparks As Big

As Castles.

The annual Shaykh Zayed Book Awards are given in nine categories in honor of the late ruler of Abu Dhabi and president of the United Arab Emirates, Shaykh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan. The awards recognize “significant cultural achievements in Arabic culture” by “innovators and thinkers in the fields of knowledge, the arts and humanities.”

|

| Choosing among vendors from more than 60 countries, a family looks over an encyclopedia. |

Founded in 1987 as a modest open-air book bazaar, the fair’s transformation into the leading publishing fair in the Gulf region began in 2007. Then, the Abu Dhabi Authority for Culture and Heritage, which oversees the fair, began a joint venture called Kitab (“book” in Arabic) with the Frankfurt fair, which is roughly ten times the size of the adibf, and tasked Kitab with the fair’s makeover. Since last year, Kitab has been headed by Monika Krauss, who was born in Baghdad to Iraqi and German parents and has spent much of her adult life in Europe. Kitab was founded, Krauss points out, to carry out the goals of “raising the standards of professionalism within the publishing industry across the Middle East and North Africa, and fostering the culture of reading.” What that culture needs most, Krauss says, is more books, as evidenced by both the number of exhibitors at Abu Dhabi, which has more than doubled in four years, and the popularity of the signings, awards, children’s contests and readings at the fair. (Other regional book fairs have grown, too: See sidebar below.) “There is an appetite across the Emirate of Abu Dhabi and the wider Arab world for reading and books,” says Krauss.

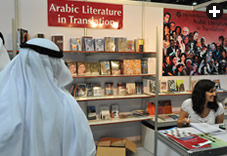

Fueling of this appetite is translation. In addition to subsidizing some 223 translation deals made at this year’s fair with grants of $1000 each, the fair also hosted the emirate’s largest translation organization, Kalima (Arabic for “word”). Its director, Ali Bin Tamim, explains that, like such other initiatives as Tarjem, based in Dubai, Kalima funds the translation and publication of “important” world books into Arabic, with the aim of boosting the historically low numbers of books that have been translated into Arabic during the modern period. It currently translates from languages as varied as Kurdish, German, Italian and Hindi, but plans to expand into others soon.

Fueling of this appetite is translation. In addition to subsidizing some 223 translation deals made at this year’s fair with grants of $1000 each, the fair also hosted the emirate’s largest translation organization, Kalima (Arabic for “word”). Its director, Ali Bin Tamim, explains that, like such other initiatives as Tarjem, based in Dubai, Kalima funds the translation and publication of “important” world books into Arabic, with the aim of boosting the historically low numbers of books that have been translated into Arabic during the modern period. It currently translates from languages as varied as Kurdish, German, Italian and Hindi, but plans to expand into others soon.

“We understand that translation doesn’t always convey similarities, but should also reflect differences between cultures,” says Bin Tamim. “Our mechanism is to have a country director for each language we translate from,” and from their suggestions, Kalima selects 100 titles each year for translation. According to Bin Tamim, the Kalima initiative has translated some 300 books to date, ranging from novels by Japanese author Haruki Murakami to books by American novelist

William Faulkner and Nobel-Prize-winning Indian economist Amartya Sen—with more to come.

|

| The American University in Cairo Press, left, is a leading translator of Arabic literature into English. Abu Dhabi-based Kalima, right, translates some 100 books a year from world languages into Arabic. |

Beyond translation, Al Qubaisi, who also directs the emirate’s national library, sees deeper challenges. “In Arab countries, there are no strict divisions among publishers, wholesalers, and distributors,” he explains. “And there are very few bookstores, making it difficult to take books to market. There is a dearth of qualified translators. Last but by no means least is the fact that copyright infringement is not yet taken seriously enough.”

Compared to the corporate book publishers increasingly dominating the market in other parts of the world, the publishers attending the adibf from the Arab world are still often family-run operations that also act as their own booksellers. As Syrian publisher Kassem al-Tarras puts it: “You’re doing everything yourself. You have to not only market your books, but print them, know how to be a bookseller and handle copyright.”

To help, last year Kitab began hosting training seminars throughout the year that brought together publishers from 11 Arab countries for sessions on everything from book jacket design to electronic publishing to strategic analysis of the 300-million-consumer market that is the Arab world.

In the training program, copyright is among the hot issues, as lack of compliance with copyright laws has been a common complaint from both publishers and authors in the Arab world, and this, Krauss acknowledges, creates a barrier to business. “It’s important to show the international publishing community that this subject is being taken seriously in the Arab world,” she says. At the same time, she points out that there are real reasons publishers might try to circumvent copyright laws when faced, for example, with the barriers of import costs, tariffs and state censorship laws that can make it difficult for a new book published in one country to be available in bookstores in another. As a result, some publishers will simply reprint a foreign book locally without consulting the author. To discourage this, the adibf enforces a strict no-piracy policy among its exhibitors, and this year one publisher caught selling unlicensed editions was sent packing and told not to return for five years.

In support of Kitab’s efforts, and as an acknowledgment of the region’s growing commitment to copyright and author’s rights, the International Publishers Association held its annual copyright symposium in Abu Dhabi just before the fair opened. Significantly, as Mohammed bin Abdulaziz al-Shehhi of the emirates’ Ministry of the Economy pointed out in his opening address, “This is the first time that a copyright conference has been held in the Arab world.”

|

|

| Top: At the fair’s Book-Signing Corner, author Mahra Muhammad Bani Yas signs for young fans. Above: Poetry recitation was one of many activities in the children’s “Creativity Corner.” |

On an even more practical level, the fair this year witnessed the launch of Abu Dhabi Distribution, a pan-Arab company that plans to work with publishers and distributors throughout the Arab world to help get books into the hands of readers by developing a database for booksellers that, for the first time, lists all published Arabic books—both in and out of print—just as the US Library of Congress records all copyrighted books in the United States. Abu Dhabi Distribution is also looking into the latest print-on-demand technology, which allows readers to walk up to a machine like a vending machine in any bookstore or mall, order any book, and have it printed and bound while they wait.

For many visitors, the swarms of children at the fair, many clutching armfuls of books, may seem proof enough that there is indeed a new generation of avid book readers. The fair, says Nora Shawwa, publisher of Rimal Publications of Nicosia, Cyprus, “is making children want to read.” Shawwa has been coming to the fair for four years and keeps coming back because, as she puts it, “it’s a good forum to introduce publishers to their counterparts in the Arab world.”

|

Chip Rossetti (jjhrossetti@yahoo.com) worked as a book editor for a number of years, most recently at the American University in Cairo Press. He has written for National Geographic and Words Without Borders, and is a translator of Arabic fiction. He is currently a doctoral candidate in Arabic literature at the University of Pennsylvania. |

|

Dick Doughty (dick.doughty@aramcoservices.com)

is managing editor of Saudi Aramco World. |