|

|

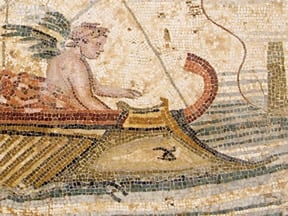

| Finished in 164 ce to honor the emperor Marcus Aurelius, this arch, above, is Tripoli’s best-known Roman monument. Starting in the second century bce, vessels like the one depicted top helped Romans turn Tripoli into an important source of wheat and olive oil. The mosaic can be seen in the Jamahiriyya Museum. |

ripoli has had many destinies. Over

the centuries, it has been ruled by Phoenicians, Numidians, Romans, Vandals, Byzantines, Arabs, Berbers, Normans, Spaniards, Turks, Italians, the World War ii Allies and, finally, Libyans, both as a monarchy and, since 1977, as a jamahiriyya, a word coined by Muammar Qadhafi that can be translated as “people’s republic.” It has been ruled by an emperor, a king (more than once), a sultan, a pasha, a Four Power Commission and today, in the latest of its destinies, by the Leader (al-qa‘id) of the jamahiriyya.

ripoli has had many destinies. Over

the centuries, it has been ruled by Phoenicians, Numidians, Romans, Vandals, Byzantines, Arabs, Berbers, Normans, Spaniards, Turks, Italians, the World War ii Allies and, finally, Libyans, both as a monarchy and, since 1977, as a jamahiriyya, a word coined by Muammar Qadhafi that can be translated as “people’s republic.” It has been ruled by an emperor, a king (more than once), a sultan, a pasha, a Four Power Commission and today, in the latest of its destinies, by the Leader (al-qa‘id) of the jamahiriyya.

This history has created a fascinating mixture of cultures and traditions that remains unfamiliar to most westerners since it’s only in recent years that Libya has begun to normalize its relations with the West. While international businesses are actively seeking sales and contracts in Libya, especially in the oil sector, tourists remain scarce, in part due to Libya’s visa restrictions. Yet visitors find much awaiting them.

At first impression, Tripoli lacks the daily circus-like atmosphere of Marrakech’s

Djemaa el-Fna or the labyrinthine streets of Fez, Tunis or Aleppo, throbbing with the pulse of daily life. It lacks the clean and orderly visage of Jerusalem. Tripoli is more reserved, less likely to grab your wrist and tug you into a shop to purchase some “antique” of questionable authenticity. Tripoli sits and waits. It waits for you to probe gently on your own to find its hidden treasures, with no urgency to complete some transaction.

The roots of the Tripoli madinah are deep. From the eighth century bce onward, the North African coast was colonized first by Phoenicians and then by Greeks. (In the Punic language, it was called Ui’at; in Latin it was Oea.) It may have been settled as early as the seventh century bce as part of Carthage’s effort to tighten its hold on the North African coast from the Gulf of Sirte to the Atlantic, but unfortunately the western Phoenicians left no written records. We do know that Phoenicians founded Sabratha, Oea and Leptis Magna (to use their Roman names) and that they introduced the cultivation of olive trees to this region. The Romans named the region “Tripolitania” because of the existence of those three cities. Initially little more than rest and repair stations for the Phoenician sailors, under the Romans, from the second century bce to the fifth century ce, those cities became important trading ports that shipped large quantities of olive oil and wheat to Rome.

No ruins remain in Tripoli from the Phoenician period, but the arch in honor of the emperor Marcus Aurelius, finished around the year 164, provides dramatic evidence of the Roman presence. (It was carefully cleaned and restored by the Italians in the years after their invasion in 1911, when they were eager to reassert their historic ties to the area.) A photo in The Gateway to the Sahara, by Charles W. Furlong, published in 1909, shows only the upper half of the arch above ground and the archway itself filled in with a wall, a door and a window. It was being used, according to Furlong, “as a shop for a purveyor of dried fish, spices, and other wares.” The situation of the arch today offers the clearest demonstration of how much higher the ground level of the madinah is now than it was in the time of the Roman city some 18 centuries ago. This further suggests that additional structures, Roman or even Phoenician, may lie under present-day buildings, awaiting future construction projects to bring them to light.

As Africa prospered from its trade with Rome, it gained political influence there, too. Vespasian became emperor in 69 ce and was the first to appoint a North African as a senator. By the end of the second century, one-third of the Roman senate came from North Africa, and in 193, Septimius Severus, born in Leptis Magna, some 120 kilometers (75 mi) east of Tripoli, and of Punic ancestry, became emperor.

|

| Characteristic of madinahs throughout North Africa and the Middle East, narrow streets lined with shops, usually with homes above, keep modern shoppers and merchants cool, much as they have for centuries. |

In the mid-fifth century, the Vandals of Europe crossed the Straits of Gibraltar and moved eastward, taking control of North Africa. It would be more than 1400 years before Tripolitania would again be ruled from Rome. Though the emperor Justinian, in Constantinople, did reassert Byzantine rule in the mid-sixth century, no serious effort was made to defend the area when Arab armies advanced across North Africa in the seventh. It was inevitable that Roman constructions would be dismantled, their stones and columns incorporated into

new works.

A prime example of this is the crossroads in the madinah known as the Arba‘a al-Saf, where four Roman columns have been incorporated into the corners of the four buildings that define this intersection. Similarly, columns of purportedly Roman origin help support

the Al-Nagah mosque,

considered to be the

oldest standing in Tripoli today, thanks in part to major reconstruction around 1610.

|

| A stone from the Marcus Aurelius arch, carved more than 18 centuries ago, lies near the arch’s base in the madinah. |

|

| Nearby, a banner commemorates 37 years of rule by Muammar Qadhafi, who took power

in 1969. |

Because of their sustained contact over many centuries in the Mediterranean basin, 20th-century Italians tended to assume that urban Libyans had preserved, rather unconsciously, some vestiges of their long-lost Roman heritage. Perhaps seeking to emulate Septimius Severus in reverse, Benito Mussolini visited Libya three times between 1926 and 1942. During his 1937 visit, after the Libyan resistance to the Italian conquest had been violently suppressed, Mussolini declared himself “Protector of Islam” and had himself presented with “the sword of Islam” in a theatrical ceremony staged outside Tripoli. After the ceremony, flanked by two Libyans on foot carrying the Roman fasces, he rode a charger into the crowded, floodlit city—“a truly Roman entry,” as the London Times journalist reported. In 1939, a special civic status was created to reward some Libyans for loyalty to the fascist Italian government, and the state assumed responsibility for the maintenance of mosques, assisted in the organization of the pilgrimage to Makkah and even banned the sale of alcohol during Ramadan.

Today’s Tripoli madinah has suffered neglect and, unlike the much-preserved madinahs of Fez, Morocco and Tunis, has not benefited from efforts to preserve its heritage. (One study in the 1980’s found that 14 percent of the madinah’s buildings were in a state of collapse.) As Italians left after independence in 1951, and as Libyan government programs offered subsidized housing in new areas of the city, many families left the madinah. The abandoned buildings were often occupied by poor immigrants from sub-Saharan Africa who had neither motive nor means to maintain the properties.

There are a few fortunate exceptions. The tiny Gurgi Mosque, immediately adjacent to the Marcus Aurelius arch, is exquisitely decorated with Tunisian tiles and floral designs in stone inlaid by Moroccan artisans. Nearby is a house constructed in 1744 as a residence for Ahmed Pasha Karamanlı, once a cavalry officer of the elite Ottoman forces known as janissaries. In 1711, Karamanlı murdered the Ottoman governor, seized power and launched a family dynasty that ruled until 1835. From the second half of the 18th century until 1940, this building served as the British consulate; it can be visited today.

|

| The oldest mosque in Tripoli today is Al-Nagah, which is said to have been built in the 11th century or even earlier. Reconstructed early in the 17th century, its prayer hall is supported by 36 columns. |

Near the Arba‘a al-Saf intersection is the 19th-century house of another Karamanlı, Yusuf, who in May 1801 distinguished himself by being the first foreign ruler to declare war on the newly independent United States. Karamanlı ordered the flagpole in front of the American consulate chopped down after us President Thomas Jefferson refused his demand of $225,000 in tribute to assure the safety of American shipping in the Mediterranean. In response, Jefferson in 1803 ordered a naval blockade of Tripoli’s harbor and threatened invasion by an American-led force from Egypt. Yusuf signed a peace accord with the us in 1805, and the episode was later incorporated into the Marine Corps hymn with the reference to “the shores of Tripoli.” Yusuf Karamanlı’s house today is a museum that also offers rooftop views over the madinah.

Some of the finest woodwork to be found in all of Libya is close to the madinah gate leading off today’s Green Square in the popular Ahmed Pasha Karamanlı mosque, built in 1738. In this part of the madinah, the narrow streets can become quite busy in the afternoon. Souvenir shops offering rugs, blankets, leather goods, postcards and a variety of old pottery and metal utensils all stand just inside the madinah wall. An amphora lying on a pile of seemingly discarded jugs and jars reminds one of the days when Tripoli exported olive oil to Rome. Beyond the souvenir and handicraft shops are jewelry and fabric stores and arcades of ready-made clothes. Luggage is displayed on the street in front of the Karamanlı mosque, along with silken gift baskets for new brides and plastic flowers. Occasionally one must step around a customer opening a suitcase to examine its interior or a bread vendor who has set up his cart in the middle of the walkway. As one passes the mosque, approaching an outdoor café adjacent to the 19th-century Ottoman clock tower, one begins to hear the sounds of the Suq al-Ghizdir, the copper market where artisans still bend, hammer and shape metal into large globes or crescents to decorate the tops of minarets. Deeper into the network of streets are tailors bent over sewing machines and weavers squeezed into tiny workshops amid beautiful fabrics.

|

| The largest mosque in the madinah is the Ahmed Pasha Karamanli Mosque, left, which is known for its finely crafted woodwork. The Gurgi Mosque, right, features splendid tiles from Tunisia and stonework inlaid by Moroccan craftsmen. It dates to the 19th century, and it was the last mosque in Tripoli built under Turkish rule. |

Outside the madinah is the remaining evidence of Rome’s second encounter with Tripoli: Italian colonial architecture, often incorporating Islamic arches, lines the streets leading from Green Square. More cultural blending appears in the Al-Jaza’ir Mosque, a neo-Romanesque structure built in 1928 as Tripoli’s Catholic cathedral, but dedicated as a mosque shortly after Muammar Qadhafi’s assumption of power in 1969.

Italy’s occupation of Libya from 1911 to 1943 was not a happy period. Between the 1911 invasion and the final suppression of Libyan resistance in 1932, tens of thousands of Libyans died, most of them from squalid living conditions in concentration camps set up by the Italian administration. Thousands more fled to Chad, Niger, Egypt and Tunisia. Nevertheless, the exchange of ideas, culture and goods between Tripoli and Rome seemed to weather all storms. The presence of tinsel-decorated plastic evergreen trees for sale in the market during the days leading up to the birthday of the Prophet Muhammed suggests that this cross-fertilization continues despite, or even because of, the colonial experience.

|

In 2008, to offer compensation for the often brutal excesses of the colonial era and to build a foundation for future economic cooperation, Italy agreed to fund a 20-year, $5-billion development program. One major element will be a new highway linking Libya to Tunisia and Egypt. Also included are undergraduate and post-graduate scholarships for 100 Libyan students a year. In return, Libya has begun the investment of government funds in a number of Italian companies, and it has expressed interest in buying up to 10 percent of eni, the Italian oil company that is already the largest foreign oil company in Libya, extracting 550,000 barrels a day. In Julius Caesar’s day, the olive groves of Tripolitania furnished a million liters (265,000 gal) of oil in tribute each year, making Libya the most important source of olive oil in North Africa. With the passage of time, it seems one type of oil has traded places with another.

In 1912, Mabel Loomis Todd—author of four books before Tripoli the Mysterious and the editor of Emily Dickinson’s poems—wrote, “One of the last regions in this over-traveled world not only unswamped, but even unnoticed by tourists, the old Tripoli of Punic and Roman days and of later [Muslim] supremacy can never again retreat into the obscurity of centuries.”

I think Ms. Todd got it right; today Tripoli awaits the next chapter in its destiny.

|

After 35 years in the us Foreign Service, Charles O. Cecil (cecilimages@comcast.net) retired in 2001 to devote himself to photography and writing. Recalled to the Service in late 2006, he spent eight months in Libya as chargé d’affaires of the us Embassy. He lives in Alexandria, Virginia. |