|

|

typecast films (2) |

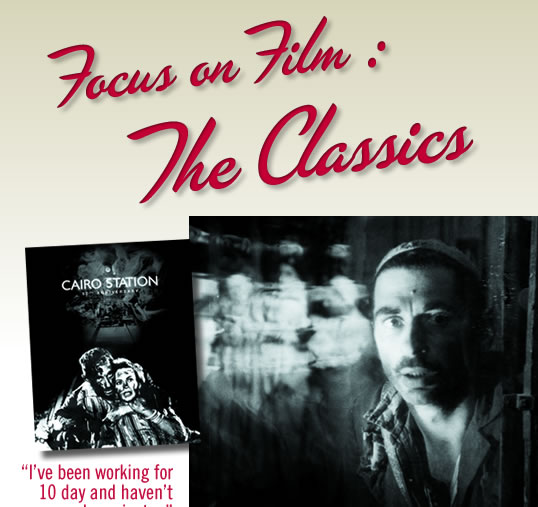

| Produced in Egypt in 1958 by Youssef Chahine, one of the country’s most prolific directors, “Cairo Station” was one of the first Arab films to adapt techniques of Italian neo-realism and American film noir limitations. |

“You can tell more about a country from a five-minute scene in a film than in 1000 cnn reports—such as the way people walk, their clothing, their means of transportation,” says John Sinno, head of Seattle-based Arab Film Distribution, the world’s largest and oldest distributor of films from the Middle East and North Africa. “Film is still the best way to learn about a country, short of going there.”

|

| In 1969, “The Cow” helped set Iranian cinema free from Hollywood imitations. |

But how to choose the best films? Classics define times and places and become enduring reference points in the world’s collective cultural memory. Like books that can be read time and again over generations for new insights and meanings, classic films contribute to our sense of an era, and indigenously produced classics do so from inside a culture rather than from the outside looking in.

“Obviously there is a major difference. It’s rare to see positive Hollywood films about the Middle East,” says Raouf Zaki, director of the 2007 film “Santa Claus in Baghdad.”

The best of Middle Eastern cinema often distinguishes itself in other, more subtle, ways, too. One is the prominence of political themes, such as the Palestinian–Israeli conflict and Islamic politics.

|

| typecast films |

| “Chronicle of the Years of Embers” tells a story of Algerian independence from an Algerian point of view. |

There is also often a distinctive use of space, notes critic Lina Khatib in her 2006 book Filming the Modern Middle East. Hollywood tends to favor grandiose, individual characters and panoramic, often overhead scenes that suggest a character’s domination of space. Middle Eastern films—which also often have modest budgets—tend to use space more intimately, through frequent close-ups and interior shots. Khatib also notes the diverse uses of gender themes: For example, while Egyptian and Algerian films tend to use gender as a mark of modernity, Palestinian cinema often links the struggle for political liberation with that for women’s equality.

So how does one sort through hundreds of indigenously produced (and co-produced) Middle Eastern films? And how do you interpret them? “A film is like a piece of literature. It’s a commentary on an issue, a window on a particular topic,” says Livia Alexander, executive director of ArteEast, a New York-based nonprofit organization that promotes artists from the Middle East and its diasporas.

“How are we going to understand how people lived in Egypt in the 1950’s? Certain films help, like ‘Cairo Station,’” Alexander says. Similarly, in “Chronicle of the Years of Embers,” there are various aspects of Algerian society you don’t get in “The Battle of Algiers.” The locally made film doesn’t focus on the fighting.”

Tracing a film’s reception in the region—by both local audiences and critics—as well as how it is received at international film festivals is one way to gauge a film’s importance. For example, the 1987 “Wedding in Galilee” marked a turning point in Palestinian film: It was the first major feature film shot inside historic 1948 Palestine to be shown at major film festivals. “If a film has done well at Cannes, San Sebastian, Berlin or Toronto, it gets into theaters,” particularly in the us, Alexander notes, cautioning that success at festivals is not always a guarantee of a film’s ability to endure. For that, she says, “ultimately, it needs to be a strong film.”

Common cinematic themes often follow a country’s political, economic and social history. For example, films from Egypt often focus on political, economic and social critique. In Lebanon, the 1975–1990 civil war and the 2006 Hezbollah–Israeli war often dominate. Algerian cinema is steeped in the 1954–1962 war for independence from France and the conflicts with armed Islamists in the 1990’s. Iranian film, with its long and prolific history, leans toward a poetic humanism and a creative use of allegory—the better to dodge the censors—making it one of the world’s most important emerging artistic cinemas. For Palestinian cinema, the Arab–Israeli conflict is “the prism everything has to go through,” says Sinno, who emigrated from Lebanon in 1984.

Filmmaking arrived in the Middle East soon after the first projections—in 1894 in New York by Thomas Edison, a year later in Paris by the Lumière brothers. Egypt, Iran and Turkey quickly established themselves as major film production centers, drawing on popular theater, coffeehouse storytellers and their traditional shadow plays. The first feature-length commercial Egyptian film, “Laila,” was produced in 1927 by a woman, Aziza Amir, who also starred in it. From the mid-1930’s to the mid-1960’s, Egyptian cinema was the world’s third largest, after the us and India, in the number of films produced. Fundamental to its success was Studio Misr, Egypt’s first fully equipped film studio, founded in 1935 by banker-investor Talaat Harb. Common genres were melodramas, musicals and comedies built around a star system that propelled to fame, throughout the Arabic-speaking world, the now-

legendary singers Umm Kulthum and Mohammed Abdul Wahab, as well as Youssef Wahbi, Anwar Wagdi and Laila Murad.

Filmmaking arrived in the Middle East soon after the first projections—in 1894 in New York by Thomas Edison, a year later in Paris by the Lumière brothers. Egypt, Iran and Turkey quickly established themselves as major film production centers, drawing on popular theater, coffeehouse storytellers and their traditional shadow plays. The first feature-length commercial Egyptian film, “Laila,” was produced in 1927 by a woman, Aziza Amir, who also starred in it. From the mid-1930’s to the mid-1960’s, Egyptian cinema was the world’s third largest, after the us and India, in the number of films produced. Fundamental to its success was Studio Misr, Egypt’s first fully equipped film studio, founded in 1935 by banker-investor Talaat Harb. Common genres were melodramas, musicals and comedies built around a star system that propelled to fame, throughout the Arabic-speaking world, the now-

legendary singers Umm Kulthum and Mohammed Abdul Wahab, as well as Youssef Wahbi, Anwar Wagdi and Laila Murad.

“Only Egyptian cinema has been able to conquer and hold Arab markets,” notes Viola Shafik, author of Arab Cinema: History and Cultural Identity. “In Egypt, Egyptian films have a market share of around 80 percent. The rest are American productions.”

|

| typecast films |

| Merzak Allouache’s 1994 comic drama “Bab El-Oued City” uses humor to sharply satirize the rise of religious extremism. |

Commercial Egyptian films attracted the largest audiences and spread Egyptian dialect and culture around the Arabic-speaking Middle East. However, art-house films—typically independently made films that treat more serious themes and have more limited distribution than popular releases—may shed more light these days on understanding the region through film.

“Important cinema is not just limited to big directors like [Youssef] Chahine,” Zaki says of the famed Egyptian director. Other filmmakers of note include Lebanon’s Philippe Aractingi, Iran’s Abbas Kiarostami and Tehmineh Milani, and Palestine’s Elia Suleiman.

As Middle East cinema continues to flourish and gain international recognition, expect more classics-in-the-making.

For Sinno, one such “new classic” film is the 2005 Tunisian/French production “Bab ‘Aziz,” part of a trilogy directed by Nacer Khemir. Cinematographically stunning, it is a mystical tale about a young girl who follows her elderly grandfather into the desert of the soul in search of a gathering of dervishes. “‘Bab ‘Aziz’ shows the spiritual side of Islamic civilization, with the desert as a source of inspiration,” he says. “The foundations of Middle Eastern culture are based on assumptions of the desert—infinite spaces, desolation. People of the forest have abundance. People of the desert, scarcity. Individualism is not necessarily an asset. Those values of the communal over the individual have been transmitted all over the Middle East,” Sinno explains.

As for classic Middle Eastern films that define cultural and political moments, filmmakers, scholars, critics and distributors frequently name the following titles for their enduring merit and their relationship to larger political and social themes.

Cairo Station

(Youssef Chahine, 1958) Suspense thriller set in a Cairo train station that represents all of Egyptian society. An unblinking portrayal of alienation, repression, madness and violence among society’s marginalized. One of the first Arab films to adapt techniques of Italian neo-realism and American film noir. www.arabfilm.com

The Cow

(Dariush Mehrjui, 1969) Masht Hassan owns the only cow in a remote and desolate village, and he treats it as his child. When he is away, his cow is killed. Masht returns home and, devastated, gradually comes to believe he is the cow. Among the first films to break from the film Farsi mold that mimicked Hollywood and establish a direction toward a more authentic Iranian cinema. www.arabfilm.com

Hope/Umut

(Şerif Gören and Yılmaz Güney, 1970) A destitute carriage driver from Adana leads a life of misery, struggling to make ends meet for his wife, five children and aging mother. He invests all his hope in lottery tickets, but fortune’s smile does not fall on him. In the end, his only way forward is to hunt for buried treasure under the direction of a hoja (religious teacher) with a reputation for clairvoyance. Influenced by Italian neo-realism in its stark portrayal of ordinary lives, and devoid of cliché, this is considered to be the beginning of new Turkish cinema. http://cgi.ebay.com

Still Life

(Sohrab Shahid Saless, 1972) This simple portrait of a static life, which provides food for thought on the purpose and direction of all life, is credited with initiating Iran’s distinct blend of highly poetic and political cinema.

The Dupes

(Tawfek Saleh, 1972) Set in Iraq in the 1950’s, this pan-Arab production follows the plight of three Palestinian refugees who try to escape their impoverished and hopeless lives to get work in Kuwait. Based on Palestinian writer and artist Ghassan Kanafani’s novella Men in the Sun, this is one of the first Arab films to address issues of Palestinian displacement and diaspora within Arab lands. www.arabfilm.com

|

|

| typecast films |

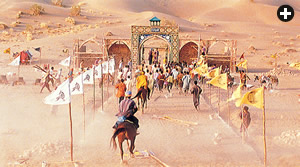

| Above and top: Poetic and lyrical, “Bab ‘Aziz” speaks to the values of desert peoples, among

whom “individualism is not necessarily an asset,” says film distributor John Sinno. |

Chronicle of the Years of Embers

(Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina, 1975) The story follows a peasant’s migration from his drought-stricken village to his eventual participation in the Algerian resistance movement just prior to the outbreak of the 1962 war of independence against French colonial rule. Antidote to “The Battle of Algiers.” www.arabfilm.com

Mohammed, Messenger of God

(Moustapha Akkad, 1976; The Message in us distribution.) This historical epic is the first and only Hollywood production to portray the story of Islam. Director Akkad saw the film as a way to bridge the gap between

western and Islamic countries. Arabic and

English versions of the film were made simultaneously with an Arab cast for audiences in the Middle East. www.amazon.co.uk

Where Is My Friend’s Home?

(Abbas Kiarostami, 1987) This key film behind Iranian cinema’s popularity in the West uses minimal dialogue, slow pacing and purposeful, realistic acting to tell the story of an eight-year-old boy who must return his friend’s notebook that he took by mistake, lest his friend be punished by expulsion from school. www.amazon.com

|

| Bushra Karaman plays the bride in Michael Khleifi’s 1987 film “Wedding in Galilee.” |

Wedding in Galilee

(Michel Khleifi, 1987) A Palestinian seeks Israeli permission to waive the curfew to give his son a fine wedding, and the military governor’s condition is that he and his officers attend. The first internationally acclaimed film of the increasingly influential Palestinian cinema, produced in the political context of the beginning of the first Palestinian intifada. www.arabfilm.com

Bab El-Oued City

(Merzak Allouache, 1994) Comedy/drama set in Algiers in 1989, during the rise to power of Islamic fundamentalism. Boualem works at night in a bakery and steals the loudspeaker that was installed on his roof to broadcast the imam’s message. This blunder is used by the Islamists as a pretext to put the district under their control. The film warns of the dangers of religious extremism. www.cduniverse.com

Bab ‘Aziz: The Prince Who Contemplated His Soul

(Nacer Khemir, 2005) A blind dervish and his spirited granddaughter wander the desert in search of a great reunion of dervishes that takes place every 30 years. This poetic, lyrical road movie speaks to the values of the peoples of the desert and the cultures they have created. It is almost too new to be called “classic”—but it’s so good, the label is likely to stick. www.typecastfilms.com

|

Suzanne Simons (simonss@ evergreen.edu) is a member of the Middle East Studies Association’s film festival committee and a visiting

faculty member at The Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington. |