|

| doha tribeca film festival |

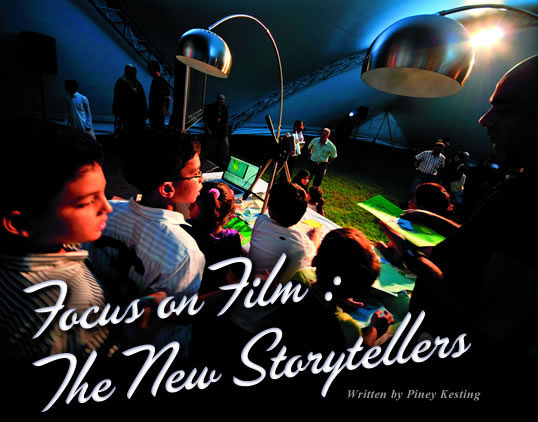

| The Doha Tribeca Film Festival offers workshops—including this one in animation—for young future filmmakers. |

|

|

| courtesy of amin matalqa |

| Nadim Sawalha endears himself to local children —and his audience—as the airport janitor who is mistaken for a pilot in “Captain Abu Raed.” |

|

Arriving from Saudi Arabia, Lebanon, Egypt, Algeria, Palestine, the us and Jordan, these men and women shared their common passion for filmmaking at the fifth annual Rawi Middle East Screenwriters Lab, where well-known creative advisors shared their expertise with the youngest generation of Arab and Arab-heritage filmmakers.

|

| royal film commission |

| At the Rawi Middle East Screenwriters Lab in Jordan, director Yusry Nasrallah from Egypt listens to a student’s script. |

Rawi is one of the most ambitious of more than half a dozen initiatives, launched mostly in the last three years in the Middle East and the us, that are responding to the rising “new wave” of filmmakers and growing audience interest in films from the Arab world. From the Doha Tribeca Film Festival with its new, year-round educational programs to the Red Sea Institute of Cinematic Arts in Aqaba, the list also includes the Centre Cinématographique Marocain, the Screen Institute Beirut, Dubai Studio City, Abu Dhabi’s Twofour54 and film fund Imagenation, and Jordan’s Royal Film Commission. “I can’t keep track of all the new film-related initiatives in the Arab world anymore,” says Reem Bader, manager of Rawi. She attributes much of this to digital technology and the new accessibility it offers to the medium. “Through the Internet, YouTube and international media,

film has become a much larger part of

Arab culture.”

|

| royal film commission |

| Michelle Satter, founding director of the us-based Sundance Institute’s international Feature

Film Program, supports the Rawi Lab. “We continuously look around the world to find the most exciting new voices,” she says. “The next generation of artists is here.” |

Rawi was created in 2005 by the Royal Film Commission (rfc) of Jordan in partnership with the Sundance Institute in Utah. Since then, 37 new-generation filmmakers have attended. In 2005, fewer than 20 applications were submitted for the Lab’s seven or eight fellowship slots; in 2009, more than 150 applications came in.

“We believe in these young filmmakers. They are the seeds of filmmaking in the Arab world,” explains Mohannad Al-Bakri, whose title at the rfc is “Capacity Building Manager.” Rawi, he explains, is a word that means “storyteller” in Arabic. Writer and director Tony Drazen was a creative advisor at the 2009 Lab. “What I found very compelling,” he says, “is that most of the filmmakers wanted to tell profoundly dramatic stories about growing up in one of the

Middle Eastern countries. The group was exciting. Even if the scripts weren’t all well developed, the filmmakers and writers were very passionate people with intense life experiences.”

Cherien Dabis, writer and director of “Amreeka,” and Palestinian filmmaker Najwa Najjar, who wrote and directed “Pomegranates and Myrrh”—both films that premiered last year—are alumnae of the first Rawi Lab. “It was life-changing. I had given up on my script, but by the time I left the workshop, I had renewed faith in the story and in my characters. I wouldn’t have finished my script if not for them,” comments Najjar. Her film has gone on to win awards in regional and international film festivals.

|

|

| national geographic entertainment |

| Director Cherien Dabis, left, credits “hours of free advice” at the Rawi Lab with helping her finish her acclaimed debut “Amreeka.” Lower: Alia Shawkat plays the independent-minded Salma. |

|

| national geographic entertainment |

“I was on the 12th draft of my script when I attended Rawi,” explains Dabis. The advice she received at the workshop, she notes, was crucial to its further development, though she nonetheless went through 12 more drafts over the next two years. “I had amazing screenwriters like Zachary Sklar, who read my script and offered hours of free advice,” exclaims Dabis. The story of a Palestinian mother and son who emigrate from the West Bank to rural Illinois against the backdrop of the 2003 invasion of Iraq, “Amreeka” premiered at the Sundance Film Festival and was released later that year for world distribution by National Geographic Entertainment. Designated one of the top 10 independent films of 2009, it was also a finalist for a coveted Gothdam Spirit Award.

Dabis and Najjar both returned to Rawi in 2009 as mentors and creative advisors. “This encourages aspiring filmmakers,” explains Michelle Satter, founding director of the Sundance Institute’s Feature Film Program, which has also supported filmmakers’ institutes in Latin America. “We want to be a beacon of inspiration, ” she says. Years ago, she adds, she realized that “the Middle East was a part of the world we weren’t hearing enough from. We continuously look around the world to find the most exciting new voices. Our interest in the Middle East came out of a sense that there is a bubbling of new talent and that the next generation of artists is there. Their work is very sophisticated. It is an exciting moment.”

Amanda Palmer, executive director of the Doha Tribeca Film Festival (dtff) in Qatar, emphasizes the region’s history in filmmaking, particularly in Egypt, Lebanon, Iran and pre-war Iraq. “However, in the past five years, there has been more of what we call the ‘new wave’ of Arab filmmakers. These are the young filmmakers who have a cinema education and who know how to make big-budget films.” More than 70 percent of the population of the Middle East is under the age of 30, says Palmer, and many in this Internet-savvy, well-traveled generation “have seen far more western films than I ever will. They are much more sophisticated cinematically than many people give them credit for,” she observes.

Amanda Palmer, executive director of the Doha Tribeca Film Festival (dtff) in Qatar, emphasizes the region’s history in filmmaking, particularly in Egypt, Lebanon, Iran and pre-war Iraq. “However, in the past five years, there has been more of what we call the ‘new wave’ of Arab filmmakers. These are the young filmmakers who have a cinema education and who know how to make big-budget films.” More than 70 percent of the population of the Middle East is under the age of 30, says Palmer, and many in this Internet-savvy, well-traveled generation “have seen far more western films than I ever will. They are much more sophisticated cinematically than many people give them credit for,” she observes.

|

“There is also a hunger among people in the region to tell their stories and to be acknowledged for their work, something which is happening more and more at international film festivals such as Cannes and the Berlinale,” Palmer comments. At the 2009 Venice Film Festival, she explains, there were many films previewed from these new Arab and Arab–American filmmakers, and “not just because they are Arab films, but because they deserve to be seen.” For example, she adds, “Palestinian writer and director Elia Suleiman is not just a great Arab filmmaker—he is a great filmmaker.”

The dtff was formed in 2008 through a partnership between Shaykha Al Mayassa bint Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani of Qatar and Tribeca Enterprises in New York. Spearheaded by Palmer (who is also the head of entertainment at Al Jazeera English, based in Doha), dtff’s main goal is to boost regional talent. In November 2009, the Festival launched a series of year-round educational programs to train local and regional filmmakers. According to Palmer, Doha has only eight local feature-film makers at present, but Qataris of all ages have been attracted to the educational programs—in particular the One Minute Film program run by Skandar Copti, the Oscar-nominated Palestinian director of “Ajami.”

|

| human film (2) |

| A “road movie” that follows a grandmother and grandson in search of their son and father, “Son of Babylon,” by Iraqi writer and director Mohamed Al-Daradji, below, is his second film made in post-war Iraq with a mostly Iraqi crew. (His first, “Ahlaam,” received more than 20 awards.) “No one believed I could make the film in Iraq,” he says. An official selection for the 2010 Sundance Film Festival, it sold out every viewing there and at the Berlinale. |

|

The upcoming dtff in October will increase the number of Arab films shown and add a competition for best Arab film and best Arab filmmaker, as well as two audience awards for best narrative film and best documentary film. Each of the four awards will carry a $100,000 cash prize. In a press release announcing the 2010 Festival, Geoffrey Gilmore, Tribeca’s chief creative officer, noted that “all throughout the [2009] Festival, people commented on the strength and quality of the Arab films. This led us to add an Arab filmmaking competition … to firmly place these films on center stage.”

Rasha Salti is creative director of Arte-East, a New York-based international nonprofit organization founded in 2003 to raise public awareness of artists from the Middle East and their work. She cautions against “lumping” together Arab filmmakers, who live and work in their home countries, with Arab–American filmmakers, who live in the us and work either there or in countries of the Arab world. “Their situations are very, very different,” Salti notes. “And there are remarkable differences regarding conditions of production, possibility of making films, distribution and screening among the countries in the Arab world, too.” She adds, however, that, in addition to earning increased international acclaim, this new generation of Arab filmmakers “is also beginning to develop local audiences.”

|

This role of the audience is critical, confirms Rajendra Roy, film curator at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. “Cinemas can’t exist in a vacuum,“ he says. “Ultimately it is up to the audience to embrace the narratives and the directors. The new wave of Arab and Arab–American independent filmmakers has taken cinema and used it to relay a contemporary story of the Arab experience and also to work as a counterpart to narratives created through mass media.” Roy was among the curators who choose “Amreeka” as the opener for the 2009 New Directors/New Film Festival. “‘Amreeka’ was chosen for Dabis’s directorial talent, but also for the humanness of the film, which has a way of connecting with the audience on a level that is rare for first-time films,” he says.

|

| courtesy of kamal aljafari (2) |

| “Once people have an opportunity to see our films and hear our stories, they can easily relate to the situation,” comments Palestinian filmmaker Kamal Al Jafari (top). Currently a fellow at the Radcliffe-Harvard University Film Study Center in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Al Jafari makes evocative films that include “The Roof” and “Port of Memory,” above. |

“I was blown away by ‘Amreeka,’” exclaims Jim Zogby, president of the Arab American Institute in Washington, d.c. “It is a remarkable movie because it captures a lot of the post-9/11 tensions and tells so many substories. Cherien did all of us—not just Arab–Americans—a real service. In the genre of literature and film about the immigrant experience, this is one of the very few films that not only captures the Arab–American experience but also has lessons for other immigrant communities.”

Four years ago, he says, “we used to say that we need to see more Arab–Americans in the media. Well, now it’s happened. We have great journalists, novelists and filmmakers. This new generation, unlike mine, is beginning to take the story and make it part of the general culture.”

Film producer Melissa Hibbard, co-founder of Fictionville Media in Brooklyn, New York, notes that a confluence of events during the last decade has made it easier for these new filmmakers to produce and market their films to a wider range of audiences. “Access to inexpensive equipment, changes in technology, instant access to the rest of the world through the Internet and a greater [public] interest in learning about the Middle East in the aftermath of 9/11 are ingredients that created a good environment for these filmmakers to become a part of the international community,” explains Hibbard.

|

| courtesy jackie Salloum |

| Jackie Salloum followed musicians in Gaza to make “Slingshot HipHop.” |

A growing number of new-generation Arab–American films, as well as debut films from the Middle East, began to appear around 2005. In 2007, “AmericanEast,” starring Tony Shalhoub, the Emmy-winning star of the hit television series “Monk,” became the first Arab–American film produced in the United States. Jackie Salloum’s short 2005 film, “Planet of the Arabs,” was an official selection of that year’s Sundance Film Festival, and “Slingshot HipHop,” her first feature-length documentary, about the Palestinian hip-hop group Dam, premiered in 2008 at Sundance’s Documentary Competition.

|

| courtesy haifaa al-mansour |

| “People want to listen to us—and we are enjoying the moment!” says Saudi Arabia’s first female filmmaker, Haifaa Al-Mansour. |

A Palestinian–American from Michigan with no formal film training, Salloum’s latest project took more than four years to produce, not only because of the difficulties of filming in Gaza but also because she funded the film in part with wages earned in her parents’ ice cream shop. “It’s really important that Arabs get into making films that go mainstream,” asserts Salloum. “We need to challenge stereotypes, and since most Americans learn about other cultures through television and film, this is the most powerful tool.”

Raouf Zaki, an independent Egyptian–American cameraman, writer and director who lives in Massachusetts, sees the new filmmakers as “more realistic and, in a sense, Americanized.” His film “Santa Claus in Baghdad,” winner of the Kids First International Film Festival, is a touching short film set in Iraq during the 2000 embargo. “When we experience other people’s stories through film or literature, we reach a greater level of understanding,” explains Zaki, who has made his film available free on-line to educators.

|

| courtesy ra vision productions |

| Raouf Zaki has made his short, touching film “Santa Claus in Baghdad” available free to educators. |

Lebanese filmmaker Hisham Bizri, cofounder of the Arab Institute of Film in Lebanon and a professor at the University of Minnesota, is concerned that filmmakers know their way around their own history as well as that of Hollywood and the international film circuits. “Our role as filmmakers in society is very important,” emphasizes Bizri. He wants to see a story coming out of the Arab world, he says, that is both nourished by the rich history of world cinema and deeply rooted in Arab culture. “The poetry that came out of the Arab world in the 10th century could be a great example for today’s filmmakers,” he says. Bizri’s films have been shown internationally, including at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Centre Pompidou in Paris, and his work was recently highlighted at Mizna’s sixth Arab Film Festival in St. Paul, Minnesota.

Leadership is important to Sundance director Satter, too. “I believe that filmmakers in certain parts of the world can lead a country and be a source of inspiration for the next generation of storytellers,” she says. Haifaa Al-Mansour, the first female Saudi filmmaker, may be one such person. As a participant in the 2009 Rawi Lab, Al-Mansour was surprised and delighted to find herself in the company of other female filmmakers. “I think female filmmakers in the Arab world are on the cutting edge of filmmaking, and we have a voice the world wants to hear. People want to listen to us—and we are enjoying the moment!

“We are a new generation of filmmakers who want to create a space for ourselves,” explains Al-Mansour. “We want to talk to the rest of the world and create a different voice—one that is tolerant and open. As a Saudi filmmaker, I want my voice to reflect my own culture, but ultimately, I want my films to be entertaining enough to build bridges between cultures.”

|

Piney Kesting is a Boston-based free-lance writer and consultant. Inspired by her first visit to Lebanon many years ago, she has been exploring and writing about the Middle East ever since. Published internationally, she is a frequent contributor to Saudi Aramco World. |