|

| pete m. wilson / alamy |

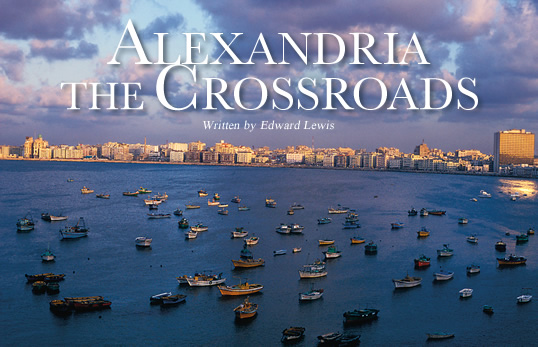

| The harbor that made Alexandria’s maritime trade possible still offers a sweeping view of the city that, at first sight, betrays little of its illustrious history. |

|

| johann adam delsenbach / bridgeman art library |

| The Pharos lighthouse, which guided centuries of sailors to the harbor and was long regarded as among the Seven Wonders of the world, was destroyed some 240 years before this colored engraving was made in 1721. |

isitors to Alexandria are usually surprised by two features: the extent to which the city contributed to and shaped the Mediterranean world, and the complete lack of physical evidence that demonstrates that role.

isitors to Alexandria are usually surprised by two features: the extent to which the city contributed to and shaped the Mediterranean world, and the complete lack of physical evidence that demonstrates that role.

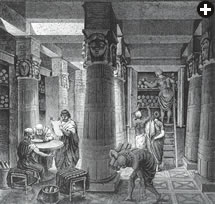

This is, after all, the city that hosted the renowned Library of Alexandria in the last three centuries bce and could boast such resident scholars as Euclid, Ptolemy and Eratosthenes, the city where the Pharos lighthouse, one of the ancient Seven Wonders, guided vessels from all over the known world to her prosperous port. Alexander the Great founded the city in 331 bce. And Mark Anthony, Cleopatra, Julius Caesar and the woman mathematician Hypatia, all, for part of their lives at least, contributed to Alexandria's development into a metropolis with a backdrop of magnificent palaces, temples and public edifices decorated with luxuries from Europe, Africa and the East. Such was the Alexandria's prestige that Diodorus Siculus, in the first century bce, described her as “the first city of the civilized world.”

Yet aside from the outline of the impressive new Bibliotheca Alexandrina, successor in 2002 to the city's great library, or the 15th-century fort that guards the harbor entrance, modern Alexandria's panorama gives no clue she was once the center of commerce and culture in Egypt, let alone the Mediterranean. Fast-paced building projects and earthquakes have made archeology only a partial, often clouded, window on the city's past. As a result, great emphasis is placed on the written record, with which, fortunately, ancient Alexandria is amply blessed. Travelers, geographers and historians documented the city's topography, her array of impressive buildings, her mixed population and her political structure, giving voice to a past city that has otherwise virtually disappeared.

Yet aside from the outline of the impressive new Bibliotheca Alexandrina, successor in 2002 to the city's great library, or the 15th-century fort that guards the harbor entrance, modern Alexandria's panorama gives no clue she was once the center of commerce and culture in Egypt, let alone the Mediterranean. Fast-paced building projects and earthquakes have made archeology only a partial, often clouded, window on the city's past. As a result, great emphasis is placed on the written record, with which, fortunately, ancient Alexandria is amply blessed. Travelers, geographers and historians documented the city's topography, her array of impressive buildings, her mixed population and her political structure, giving voice to a past city that has otherwise virtually disappeared.

|

| erich lessing / art resource |

| From Jerash, Jordan, a sixth-century mosaic shows a simplified view of Alexandria. |

|

| georg braun and franz hogenburg / v&a images / art resource |

| A thousand years later, a colored engraving shows a walled city with a harbor marked by the Pharos on the left and a fortress on the right. |

The Greek geographer Strabo was clearly taken with Alexandria when he visited around 20 bce. “In short, the city ... abounds with public and sacred buildings,” he wrote in his Geography. “Among the happy advantages of the city, the greatest is the fact that this is the only place in all Egypt which is by nature well situated with reference ... both to commerce by sea, on account of the good harbors, and to commerce by land, because the [Nile] river easily conveys and brings together everything into a place so situated—the greatest emporium in the inhabited world.”

If Alexandria's ancient period is well documented, her medieval past is anything but. The year 641 ce, when the city was conquered by Muslim forces led by 'Amr ibn al-'As, is often viewed simply as the end of the Greco-Roman and Byzantine ages: a full stop at the end of an extraordinary era. Due partly to the lack of written sources and partly to her eclipse by other Egyptian cities, Alexandria's history under the flags of successive Islamic dynasties is somewhat neglected and often dismissed as a story of decline, regression and isolation.

Islam's ascendance profoundly impacted Alexandria and port cities elsewhere in the Mediterranean. “Within 80 years of the death of [the Prophet] Mohammed,” wrote Belgian medievalist Henri Pirenne in Mohammed and Charlemagne, “Islam extended from western Turkistan to the Atlantic Ocean. Christianity, which had embraced the entire Mediterranean coast, was confined to its northern shores. Three-quarters of the coastlands of this sea, once the focal point of Roman culture for the whole of Europe, now belonged to Islam.”

The fact that Alexandria, so long Egypt's principal city, was vulnerable to attack by the Byzantine fleet, however, persuaded the reigning caliph 'Umar ibn al-Khattab to order his generals to relocate to a more protected position. Misr al-Fustat, located some 225 kilometers (140 mi) to the south, became the seat of power. Shielded by a vast and unforgiving desert and served by the Nile, it developed into Egypt's new trading center; Alexandria could only watch as the focus of power turned from the Mediterranean shore to the interior.

|

| top: travelpix / alamy; Below: bridgeman art library (2) |

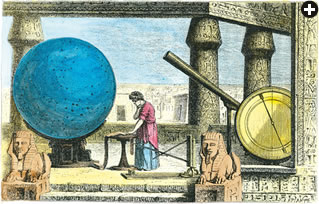

| The 2002 Bibliotheca Alexandrina, above, is the modern successor to the ancient Mediterranean’s greatest center of learning, the library that burned in 48 bce (lower right). It was already a long-lost memory by the second century ce, the time of the astronomer and geographer Claudius Ptolemaeus (known as Ptolemy), depicted below in a 19th-century French lithograph. |

|

|

The result was staggering. In just a few hundred years Fustat (and later its successor city, Cairo, a few kilometers away) became the wealthiest city in the world, according to the Persian geographer al-Qazwini, who lived there. Trade was reoriented, primarily toward Asia, with commodities passing through harbors on the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean. Under the Fatimid Dynasty (969–1171), Fustat's markets burst with goods from Jiddah and the Hijaz, Sana'a, Aden and Muscat, and India and China. These included spices, pearls, precious stones, silk, porcelain, teak, linen, perfumes and paper—the latter unknown in Europe at that time.

But in spite of the long shadow cast by Fustat and then Cairo, Alexandria did not become a backwater. The city continued to capitalize on her prime location, maintaining herself as an important Mediterranean port and providing a highly prosperous link between East and West and among Muslims, Christians and Jews. “Without the city of Alexandria, Cairo with the whole of Egypt could not survive,” wrote a Venetian observer in the Middle Ages.

The limited written material available indicates that relatively little changed in Alexandria during the first few centuries of Muslim rule. The administrative system used by the preceding Byzantine government continued, with a few minor amendments, and the physical makeup of the city doesn't appear to have altered drastically. Although the Library of Alexandria, the center of Hellenistic learning, had all but disappeared by the fifth century, early Arab accounts marvel at Alexandria's wide streets, use of marble, beautiful and intricate pillars, water cisterns, palaces, luxurious temples and harbors. The 10th-century geographer Ibn Hawkal wrote:

One of the famous cities of the country, whose antiquities are marvellous, is Alexandria, located on a string of earth, on the Mediterranean shore. There you can see very visible antiquities and authentic monuments from its ancient inhabitants, impressive heritage of royalty and power, and that shows its domination over other countries, its greatness, its glorious superiority and they represent both a warning and an example.

One attraction that most certainly remained long into the Islamic period was the Pharos. In spite of its age and disrepair, Alexandria's iconic landmark—already some eight centuries old when Muslim armies arrived—continued to be an object of wonder to all who saw it. In the 12th century, the Andalusian geographer Ibn Jubayr wrote of the famous lighthouse: “Description of it falls short, the eyes fail to comprehend it and words are inadequate, so vast is the spectacle.” The twin harbors that the Pharos marked ensured that Alexandria remained an important, if vulnerable, player in what was at times a politically volatile climate. Aside from the numerous internal clashes between rival Muslim dynasties, Alexandria was targeted by Crusader invasions on two occasions, most famously in 1365.

|

| Above and Below, Right: bridgeman art library |

| Above and below, right: In the 1840’s, David Roberts produced lithographs of two of Alexandria’s other famous monuments, “Cleopatra’s Needle” and “Pompey’s Pillar.” The pillar was actually dedicated to the Roman emperor Diocletian, and it still stands. The obelisk was one of two that in the late 19th century were moved to New York and Paris respectively. |

|

But in no way did Muslim rule inhibit commerce with Christian merchants. Indeed, trade was an important and valued activity in Muslim lands. Makkah was a trading city and the Prophet Muhammad had himself engaged in trade there in his early life. “There are no goods in the whole world which through this confluence of pilgrims are not to be found in Mecca,” observed a pilgrim making the Hajj in the 12th century, according to Ibn Jubayr. Across the Mediterranean, particularly in Italy, city-states were lining up their galleys, keen to exploit Alexandria's favorable location and diverse goods. Not even Europe's religious wars could stop the pursuit of profit, and despite a paucity of documentary material from the first centuries of Islamic rule, accounts from the 10th century onward suggest that Alexandria was, and had been, anything but a closed city.

Indeed, documents show that merchants from such cities as Pisa, Genoa, Marseille and Barcelona, in addition to ports in the Levant, docked in Alexandria, bringing an exotic array of goods. In Alexandria's harbors, a startling array of commodities would have been on display: bright silks from Spain and Sicily; pungent spices such as pepper, ginger, cinnamon and cloves from the East; slaves from southern Russia; Mediterranean coral, olive oil, timber, aromatics, perfumes and gums; and metals including iron, copper, lead and tin. Great quantities of local Egyptian produce—lemons, oranges, sugar, dates, capers and raisins—would also have been stacked on the docks to be loaded and shipped to European markets. Flax would have been piled there for export, too. Of the more unusual commodities, a powder made from ground Egyptian mummies and believed to have medicinal value was much sought after in Europe. Indeed, one English merchant shipped as much as 600 pounds of the powder back to his homeland.

Such was the extent of trade that special rest houses called

Such was the extent of trade that special rest houses called

funduqs were established to accommodate visiting traders and encourage business. While Muslim traders were free to find accommodation wherever they pleased in Alexandria, foreigners were forced to take rooms in funduqs designated for their country or city. Built around a central courtyard with storerooms and living quarters, these buildings or compounds provided secure locations in which to transact business and store merchandise. Some trading states were afforded privileges beyond their funduq; the Venetians, for example, had a church, bathhouse and bakery in Alexandria and are said to have been allowed to import cheese, among other goods, tax free. One visitor, Benjamin of Tudela of Spain, counted no less than 28 European nations or city-states with formal representation in Alexandria in 1170, including non-Mediterranean countries such as Denmark, Ireland, Norway, Scotland and England—not to mention representatives from the East.

|

| dbimages / alamy |

| The Pharos lighthouse remains a popular symbol beckoning visitors to the city. |

|

Far from being a stagnant, decaying city, medieval Alexandria at times gives the impression of a lively meeting point where different creeds and cultures mixed for the sake of commerce. Wrote the 12th-century clergyman and historian Guillaume of Tyre, “The produce unknown to Egypt arrives by sea to Alexandria from all regions of the world and are always in abundance.... Also, the people of the Orient and those of the Occident meet continuously in this city, which is like the great market of the two worlds.”

Nevertheless, suspicion of foreign merchants remained. The Crusades had devastated inter-religious relations. On more than one occasion, the Pope himself had imposed a total embargo on trade with Muslims. As a result, foreign visitors to the city were kept under close observation. Arriving non-Muslims were forbidden to enter the western harbor, and some markets in the city were restricted to merchants of a specific nationality or ethnic origin.

One event during the Crusades, Reynald of Chatillon's attempt to attack Makkah from the Red Sea in the 1180's, had particular repercussions in Alexandria. Reynald's foe, Saladin, banned non-Muslim traders from entering Egypt's interior in an attempt not only to protect the holy sites in the Levant and Arabia, but also to safeguard Egypt's valuable commercial links with the East. The result was a concentration of European traders within Alexandria's walls. One source states that no less than 3000 were jammed into the city in the early 13th century.

Alexandria's bustling trade was undoubtedly the primary reason for foreign arrivals to the city, but it was not the only one. Between the seventh and 16th centuries, Alexandria was an important harbor from which to visit the region's holy sites, whether in Egypt, Makkah or Jerusalem. Accounts of pilgrims from as far away as Ireland offer intriguing insights into religious travel at that time and the extent to which Alexandria was involved.

|

| Above: manchester art gallery / bridgeman art library; Below, Right: steven dusk / alamy |

| The streets of Alexandria, below, right, are as accustomed to the bustle of commerce today as they were in the second to fourth centuries ce, when Strabo called it “the first city of the civilized world” and an Egyptian artist used tempera to paint this young woman’s portrait, above, on linen. |

|

The itinerary for a Christian pilgrim in the Middle Ages might have included several well-known churches and monasteries in and around Alexandria, as well as locations in the Nile Valley where Jesus and his family were believed to have sought refuge during their stay in Egypt. Alexandria's position as a transit point for travelers en route to Makkah and Madinah additionally ensured that she received visitors and pilgrims from North Africa and Andalusia, the most prominent of those being Ibn Battuta, the 14th-century Moroccan traveler and chronicler, who visited the city at least twice during his extraordinary life.

The Portuguese discovery in 1498 of the sea route to India, around the Cape of Good Hope, severely damaged Alexandria's role as a trading port, diverting a huge portion of the commerce to which she had become accustomed. By this time, too, the canal that connected Alexandria to Cairo via the Nile had silted up, adding to the city's woes and forcing foreign merchants to find alternative ports.

Furthermore, sporadic outbreaks of plague in the city must have hastened their departure. Between 1347 and 1459 alone, there were no less than nine waves of plague that killed as many as 200 inhabitants per day. Although Alexandria was by no means the only Mediterranean city that suffered, the plague's impact on the city, as described by the Venetian ambassador's secretary in April 1512, was particularly hard. He recounted a city in freefall—nine-tenths in ruins and with a decimated population. The plague's effect on trade and the local labor force combined with hemorrhaging commerce as lucrative new trade routes opened elsewhere. The city's shrinking population concentrated in a small peninsula; everything outside this core was neglected.

|

| collectiva / alamy |

| As it has for centuries, Alexandria’s modern maritime economy includes tourism. |

Yet developments across the Mediterranean ensured that Alexandria was not forgotten. By the mid-17th century, news of Egypt's pharaonic past—its temples and the other remnants of an exotic and powerful civilization—had spread throughout Europe, thanks to the rise in popularity of such classical authors as Herodotus, Diodorus Siculus and Strabo, all of whom gave vivid accounts of Egypt. Moreover, references to Egypt in the Bible and accounts by pilgrims returning from their adventures in the Holy Land added to a deep-rooted curiosity about “the land of the Pharaohs,” encouraging a new type of visitor.

Soon, individuals were landing in Alexandria to study and record Egypt's intriguing wildlife or to purchase its increasingly sought-after antiquities. The royal, princely and ducal courts of Europe were keen to add to their collections of “wonders” and to be seen to be developing scientific knowledge, and they sent naturalists or antiquarians to Alexandria to acquire ancient manuscripts, coins or other antiquities. Missions set out to document Egypt's flora and fauna, which included crocodiles, hippopotami, hyenas and a large and diverse bird population.

Perhaps the greatest example of such a project was Napoleon Bonaparte's expedition of 1798–1801. One-hundred-sixty-five scholars of the Commission des Sciences et des Arts, among them astronomers, architects, geographers, zoologists and botanists, produced the Description de l'Egypte, a 23-volume work that brought Egypt to the outside world. However, Alexandria is pictured in only a handful of plates, depicted as a city of ruins.

Just as Alexandria owed her very existence to a foreigner—Alexander the Great—it was another foreigner, the Albanian Muhammad Ali, who was responsible for reviving her fortunes. Appointed governor of Egypt in 1805 by the Ottoman sultan, he established a dynasty that ruled until 1952. Muhammad Ali gradually distanced the country from the Ottoman Empire and laid the groundwork for a more modern and self-sufficient Egypt. Alexandria was at the forefront of this initiative, which encouraged foreign trade and investment and included hosting communities and consuls from around the Mediterranean, concepts also embraced by Muhammad Ali's successors. Still Egypt's “second city,” Alexandria once again built her future on exchange and interaction, the cornerstones of her past success.

Egypt's independence in 1952 marked the beginning of a new period in Alexandria's history. For the first time since her creation, she became a city governed by Egyptians. Though the doors that had previously been open to the Mediterranean and beyond swung shut under the administration of President Gamal Abdel Nasser, and the foreign contribution to the city's makeup and commerce decreased significantly, both rebounded to some extent under the open-door economic policies and liberalization of subsequent years.

Today, Alexander's city is dominated by high-rise concrete apartment blocks and busy, traffic-filled streets. However, those who listen carefully will hear echoes of the past in the cacophony of languages spoken by passengers disembarking from cruise ships, sitting in her cafes and visiting her sites, old and new. Alexandria may never fully regain her old luster, but her role as a meeting point for a range of diverse cultures and creeds appears safe.

|

Edward Lewis (ejlewis80@hotmail.com), a free-lance writer and project manager in Egypt, holds an MA in Egyptology. He has written for the Library of Alexandria, Egypt Today and The National magazine in Abu Dhabi, and has conducted cultural projects for the Anna Lindh Euro-Mediterranean Foundation for the Dialogue Between Cultures, and the Delegation of the European Union to Egypt. |