|

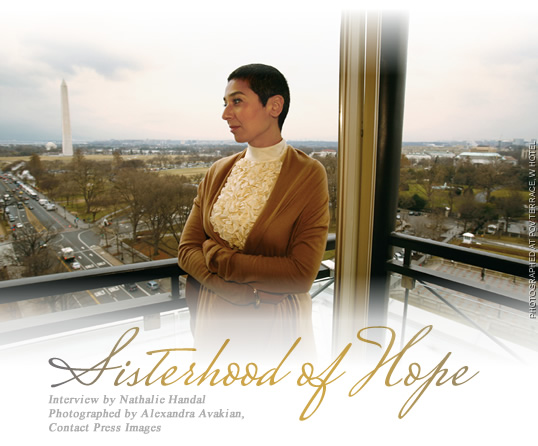

| The headquarters of Women for Women is in Washington, D.C. |

|

|

You must have Flash and javascript enabled to hear the audio track.

|

For our interview, poet and playwright Nathalie Handal spoke with Zainab at a recording studio in New York City. Listen or download here.

—The Editors |

In eight of the world's most war-ravaged countries, Women for Women International has become a successful nonprofit organization by helping more than a quarter-million affected women and their family members rebuild their lives.

Founded in 1993 by Zainab Salbi and Amjad Atallah, Women for Women provides the education, means of self-expression and access to resources that help survivors of war regain their footing in their families and their communities. For her groundbreaking leadership, Time magazine named Salbi an “Innovator of the Month” in 2005, and in 2006 Women for Women became the first women's organization to receive the world's largest humanitarian prize, the Conrad N. Hilton award. Salbi herself has appeared on the “Oprah Winfrey Show” eight times; she blogs for Marie Claire magazine and The Huffington Post.

|

| Zainab Salbi, cofounder and ceo of Women for Women International, listens near Cerkse, Bosnia-Herzegovina. At right is Deborah Lloyd of the design house kate spade, which helps market craftwork by Bosnian women in WfWI programs. |

Salbi was born in Iraq to a family then connected to the dictator Saddam Hussein: Her father was Hussein's pilot. In 1990, as her family's relations with the regime deteriorated, her mother arranged for Zainab to escape Iraq through a three-month marriage of convenience in the us. In her 2005 memoir, Between Two Worlds, Zainab Salbi recounts her life growing up and the adult journeys that led her to found Women for Women. In 2006, she published The Other Side of War: Women's Stories of Survival and Hope. She holds degrees from George Mason University and the London School of Economics.

In your memoir, Between Two Worlds, you write, “I created a whole new identity for myself as the founding president of a non-profit women's organization called Women for Women International, which supports women survivors of war.” Has your identity changed since then?

My identity went through, I would say, probably three stages. Stage number one in Iraq: As I was growing up, I was always known as the pilot's daughter. My father was Saddam Hussein's pilot, and so I grew up wanting people to see who I am, but no one could see who I am. I remember in high school or in college, my classmates would sing over my earrings, you know, half joking that I would have bugs and recorders in my earrings. It was clear that I was never seen for who Zainab was. It was more who Zainab's father was.

When I came to America, I wanted to create a completely new identity, which is: I am not going to tell anybody who I am, [I am going to] prove to myself and to those around me who I am, no longer who my associations are. So I spent my first 15 years in America establishing myself. I created Women for Women; I was living my truth. I was traveling around the world and encouraging women in war zones to break their silence and speak up and speak out, and help[ing] them rebuild their lives. And that was a different identity.

It was also an incomplete identity. It almost was like I went to the opposite, the reverse, as I wanted to show who I am, but I never showed who I am fully, because there was this background, this baggage out there, 20 years of baggage in Iraq. I was too shy and too embarrassed and, more importantly, too horrified—horrified that I would tell anybody that I knew Saddam Hussein. I literally believed that the minute I say it, people will no longer see me, and I still get emotional talking about it. I believed people will only see his face and not see what are my values, what I stand for, what I have accomplished, what are my dreams, what are my hopes.

It took me 10 years of working with women survivors of wars, and it was one of those women who I thought I was helping, a Congolese woman. Her name is Nabitu. She was 52 years old when I met her, and I remember that moment so well, because I had to drive for five hours from Congo to Rwanda, and I cried the whole time because I realized this woman had more courage than I did, [because I was] only showing my successful part, but not my vulnerable part. That's when I decided to not only write my memoir but really expose myself fully. This was me telling my full truth. It was me saying, “I can't help these women if I am not equal to them.”

How has your vision changed along the way?

Back in 1993, I started the program in September with 33 women. I remember being in a bus in Croatia, [going] from one refugee camp to another and delivering aid to these 33 women. Seventeen years later, we have helped 243,000 women, impacted about a million people, [including] their children, we have sent $79 million, and we are now working with about 65,000 women on a monthly basis, and have 10 country offices and 600 staff.

That makes me believe in the possibility of making a difference. I only started it. Really, this happened because there were 243,000 women from all over the world who chose to be part of this program. I just started an idea, and if that could happen from a refugee, or someone who had nothing in America, I really believe in the possibility of change.

We are helping people not because they are victims. “Come here if you want to stand on your feet!” I argue that refugees are the most eager to rebuild their lives because the memory of a stable life, no matter how poor or how rich they were, is very much alive.

|

| In Vogosca, Bosnia-Herzegovina, women join hands at the end of an educational course by Women for Women International that combined personal support, income-building opportunities and human rights education. |

Half of the knowledge is already there with the very people that I think I am trying to help. To give you an example, I was in Bosnia—Bosnia was the formation of Women for Women International, and the model that we do right now, so a lot of my early years were spent in Bosnia forming the program and the philosophy behind it. So I was in Bosnia, helping a woman start a chicken farm. I was asking her how many chickens do you want, the food they need, how much is a brown egg versus a white egg, and then I said, “How many eggs does a chicken give?” And she looks at me. I remember that look so vividly, because she didn't tell me, “Stupid!” but I felt it. She is like, “One egg! A chicken gives one egg!” [With] all my education, never, not once, did I remember learning that a chicken gives one egg a day. Out of all this business plan that I was trying to help her do, the most essential aspect of it was that a chicken gives one egg a day. So I learned humility in the process. It's learning and listening, stepping back and adjusting. I want to help women survivors of wars, not only “victims.” They survived that; they did not die, not spiritually, not physically. And how can we help them stand on their feet? Women thrive despite their circumstances, not because of it, and when someone invests in them, they thrive so much more. So for me, it's simply the wisest investment. I learned humility, respect [for] their agency, respect [for] their desires to be good mothers by providing whatever they choose that the kids should have. Every single aspect of Women for Women really came from the very women I thought we were helping, but they ended up teaching me.

There is a global economic crisis. How is that affecting the lives of women?

In terms of the women that we serve, people are scared of it, because it impacts the whole idea of life and death, eating or not eating. Before the financial crisis, there was a food crisis. One of our biggest projects right now is about linking the food crisis with the fact that women are 70 percent of the farmers in the world, producing 66 percent of the food in the world, earning only 10 percent of the income, and owning less than two percent of the land. We cannot talk about the food crisis and the food in the world without really facing the reality, “the elephant in the room,” that women are the majority of the farmers, not men. And women as farmers are disproportionately impacted by not having any rights in terms of farming policies, or owning land, or all of these things.

So marginalized people make up the majority of food producers, and we have a shortage of food production. We can't fix that crisis without addressing the fact that women are the majority of the farmers in the world. So a lot of Women for Women's initiatives right now, from Rwanda to Sudan to Congo, and hopefully Iraq, are where we are asking governments—Afghanistan as well—to lease us land, 200 acres, 300 acres, for a long term, from 20 years to 90 years. We then find commercial buyers who are buying produce, and we want them to deal with us commercially. And then we teach women organic farming and distribute land [to] create cooperatives, where they control the land and sell produce commercially. So we are shifting women's farming techniques from just selling her bucket of tomatoes on the side of the street to actually selling commercially and thus earning double the per capita income in countries like Sudan, for example. The per capita income in southern Sudan is $80; our women are earning $160, sometimes up to $200 a month.

Your mother taught you how life should be lived. She arranged your marriage in order to get you out of Iraq, and when she lost her voice due to her illness, she wrote to you in her notebook while you were giving voice to women in the world and, eventually, writing your memoir. What did you discover in her silence?

Your mother taught you how life should be lived. She arranged your marriage in order to get you out of Iraq, and when she lost her voice due to her illness, she wrote to you in her notebook while you were giving voice to women in the world and, eventually, writing your memoir. What did you discover in her silence?

I discovered that most women have their stories, and [most] women are silent about it. I discovered that my mother's silence was no different than my grandmother's, but more importantly, no different than most of the women I work with both in conflict areas but, frankly, in America as well, in Europe. In the process, I learned that resistance and resilience and courage come in small acts, not in grandiose acts. I realized, yes, there is Gandhi and there's Mandela, but there are a lot more courageous people. It's just their acts are not in big grandiose revolution-making, [but in] small acts of breaking the silence or doing something that would change their children's lives. I would say that was definitely the case with my mother and my father.

I discovered that most women have their stories, and [most] women are silent about it. I discovered that my mother's silence was no different than my grandmother's, but more importantly, no different than most of the women I work with both in conflict areas but, frankly, in America as well, in Europe. In the process, I learned that resistance and resilience and courage come in small acts, not in grandiose acts. I realized, yes, there is Gandhi and there's Mandela, but there are a lot more courageous people. It's just their acts are not in big grandiose revolution-making, [but in] small acts of breaking the silence or doing something that would change their children's lives. I would say that was definitely the case with my mother and my father.

I grew up with my mother telling me that I always have to be strong, that I always have to be independent, that I should always laugh and celebrate my life, and I should never cry. And this was not a neutral tone. This was a very passionate tone. From when she saw me as a kid with my schoolmates, if I was shy, she would be upset at me. To a teenager, she would tell me, you have got to be independent and you have got to be strong. These things, it was like my mother tattooing these concepts on my brain.

You grew up very much with both western and eastern traditions. Tell me a little bit about how your definition of culture has changed.

You grew up very much with both western and eastern traditions. Tell me a little bit about how your definition of culture has changed.

I don't believe culture is a set value. I think culture is a mobile concept that gets adjusted and adapted and molded in different ways, depending on the circumstances. I believe if you look at the concepts of cultures, in many, many ways they all have to do with systems of life, and the systems change. They change to adapt to the new circumstances.

You quote [a hadith, or saying, of] the Prophet Muhammad, “Home is where you are heading.” Where are you heading?

You quote [a hadith, or saying, of] the Prophet Muhammad, “Home is where you are heading.” Where are you heading?

I am someone who has navigated two worlds. My work and my passion, when I am fully alive, is where I am in Congo with the women. I may be in a slum or in a refugee camp that is horrible, but I know this is where I am supposed to be, with them. Or with Iraqi women, or with Rwandese or Afghan women, sitting on the floor with women from different countries. I am just speaking with them, talking about their stories, and seeing how we can navigate and conspire to get them jobs, stand on their feet, stop an abusive marriage, recruit her husband and improve their relationship, send the girl to school, all of that.

And then the other extreme of my life is I come to the States or to England, or wherever I am, and I meet with the most wealthy or well-known people in the world, from the media to the philanthropic [realm] to the business community. And I belong to neither, personally. I am somewhere in the middle. I realize in the process that I live in the bridge. I belong in neither world fully, but my blessing is to know how to live in both worlds, and to be at peace in both worlds.

I am a big Rumi fan, and the poem, my favorite, says, “Out beyond the worlds of right-doings and wrongdoings, there is a field. I shall meet you there. When the soul lies down in that grass, the world is too full to talk about. Ideas, language, even the phrase 'each other' no longer makes any sense.” And I fully believe that. Culture, languages, ideas [are] when you are at home, and it's irrelevant which house, which country or which land it is. When you are at peace in your heart, all of these things become irrelevant, in my opinion.

So where am I heading? For the longest time, I was anxious: Where do I belong? Do I belong in Iraq or America—or Congo, which is my favorite country actually—or Afghanistan? Where, it doesn't matter. My job is to appeal for all women and men. Women's rights, and giving equality to women, is not only a women's issue. It's really good for everyone, so how do we make that field bigger? Because once you are in that field, you'll just know that the world is so beautiful. Despite its horror, it's also a beautiful place.

In one word, how would you describe yourself today?

At peace.

|

Nathalie Handal (www.nathaliehandal.com) is a poet, playwright and writer. Her most recent books include Love and Strange Horses and a second poetry anthology, Language for a New Century: Contemporary Poetry from the Middle East, Asia & Beyond. She was a finalist for the 2009 Gift of Freedom award. |

|

As a senior photographer at Contact Press Images, Alexandra Avakian (www.alexandraavakian.com) has photographed for leading world publications since the 1980’s. Her book Windows of the Soul: My Journeys in the Muslim World was published in 2008 by National Geographic/Focal Point. |