|

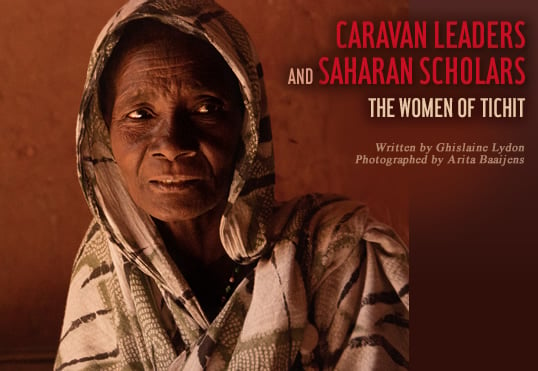

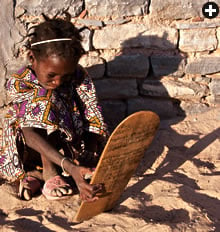

| Among the seasoned caravanners of Tichit is Tahira mint Al-Khatabi, now in her 60’s. |

Jarfuna was arriving. The whole town was alerted as soon as her caravan was spotted crossing the last dunes before the dry lakebed bordering Tichit, a once-prosperous oasis in the heart of the Islamic Republic of Mauritania. Everyone came down to greet the camel convoy with ululations, cries of excitement and praise to God for safeguarding the travelers. Such was the long-standing tradition among Saharan communities, where the departure and arrival of caravans, awaited with great anticipation, marked the high moments of the year, breaking the humdrum of everyday life.

|

| From Tichit, a caravan laden mostly with salt sets out for Ayoun el-Atrouss, 10 days’ walk distant. |

Jarfuna, a Masna woman of slave descent, was the most celebrated female caravan leader in the town's memory. She was born at the end of the 19th century and died sometime in the 1960's. She was an entrepreneur with a reputation not only for overcoming great adversity in dealing with nature and people, but also for conducting successful commercial ventures: “Jarfuna led the caravan and she rented out her own camels,” explains Shaykh Sid Ahmed Ould Baba Mine, the traditional chief of the Masna people of Tichit.

By Saharan standards, women like Jarfuna were exceptional, for Tichit is the only oasis in Mauritania—or elsewhere in the region—where women are known to have joined commercial camel convoys. Tichit women excelled in other ways as well. At one end of the social scale, women of slave origins joined caravans and engaged in trade on their own account. At the other end, women of higher status learned to read and write and traded through proxies—and some became genuine intellectuals.

Tichit lies at the foot of a long escarpment in southern Mauritania that is topped by a limestone plateau. For more than a millennium, its inhabitants thrived in a diverse and lush environment. In fact, it is here that archeologists have discovered the earliest evidence of African plant domestication outside North Africa and the Nile Valley, dating back 4000 years. Not surprisingly, scattered across the region north and east of Tichit are the stone ruins of permanent or semi-permanent dwellings of farmers, hunter-gatherers and herders—some comprising villages that had thousands of residents. These communities preceded the rise, in the eighth century, of the Empire of Ghana, whose capital was located several hundred kilometers southeast of Tichit on the border with Mali.

Tichit lies at the foot of a long escarpment in southern Mauritania that is topped by a limestone plateau. For more than a millennium, its inhabitants thrived in a diverse and lush environment. In fact, it is here that archeologists have discovered the earliest evidence of African plant domestication outside North Africa and the Nile Valley, dating back 4000 years. Not surprisingly, scattered across the region north and east of Tichit are the stone ruins of permanent or semi-permanent dwellings of farmers, hunter-gatherers and herders—some comprising villages that had thousands of residents. These communities preceded the rise, in the eighth century, of the Empire of Ghana, whose capital was located several hundred kilometers southeast of Tichit on the border with Mali.

While the history of Tichit remains debated and is largely unexplored by scholars, there is little doubt that its original inhabitants were ancestors of the Masna, a group of Soninké origin that owns majority rights over the extraction of salt from fields of amersal, a salty crust that forms after summertime rains on the lakebeds that surround Tichit; the salt is sold predominantly to herders as an animal-feed supplement. Aside from the Masna, the two other dominant clans in Tichit are the Shurfa and the Awlad Billa, the latter a nomadic clan that settled here late in the 18th century. Until the beginning of the 20th century, Tichit was a commercial crossroads where caravans from far afield met to exchange regional and international goods. After the French colonial occupation finally reached the oasis in 1911, local caravans continued to supply the town's basic needs, but trans-Saharan traffic from Morocco came to an end. Today, Tichit remains one of Mauritania's remotest desert enclaves.

|

| On the ancient lakebeds near Tichit, both men and women work to break up the salty surface crust. They bag it, load it onto camels and market it to caravanners who in turn sell it to herders as an animal-feed supplement. |

Tichit has a long tradition of excellence in Islamic learning and scholarship. As early as the 12th century, several Muslim scholars had settled in Tichit, among them Sharif 'Abd al-Mu'min. Today, there are some 20 large libraries in this Saharan oasis that contain manuscript collections bearing witness to the vibrant scholarly community that once flourished here--including the 800-manuscript library of the family of Limam Ould Abdel Mu'min, who heads the only museum of Tichit.

|

| Lying at the base of a limestone escarpment, accessible only by camels and off-road vehicles, Tichit was once so verdant that archeologists have found evidence of plant domestication going back some 4000 years. |

In recent years, the Fondation des Villes Anciennes, under the Mauritanian Ministry of Culture, has been working to preserve manuscripts in Ticht and sister oasis towns. In Tichit, some families have taken matters into their own hands by creating the Club pour la Sauvegarde des Manuscrits de Tichit, which is cataloging six family-library collections. Mohamedou Ould El-Sharif Bouya, who directs the club, is a scholar and local historian, a role passed down to him by Daddah Ould Idda, the late custodian of Tichit's history. Much material assistance is needed to secure these Saharan treasures for posterity, he says.

Several Tichit women were known as distinguished scholars, and their stories are recounted in the town's oral traditions. The mosque of Tichit, its façade decorated with the triangular niches typical of the town's stone buildings, has a special entrance for women that is notable for its beauty and size. Today women from all three of Tichit's clans still run primary schools in their homes where they teach the Qur'an and basic Arabic literacy to boys and girls.

|

Historically, many of Tichit's female intellectuals belonged to the Shurfa clan, which traces its lineage to the Prophet Muhammad. Like their male counterparts, they memorized the Qur'an to earn the respectful title of hafidhat, and some of their writings are preserved in the Club pour la Sauvegarde des Manuscrits. The earliest example is A'ishatu mint al-Faqih Abu Bakir ibn al-Amin ibn al-Sha' al-Muslimi, who lived in the 18th century. It is said that she once traded 70 camels for a single manuscript: Ibn Hajjar's collection of hadith, or sayings of the Prophet. Another example is Al-Hasniya mint Fadil al-Sharif, a 19th-century scholar. She married another scholar with whom she had four sons, all of whom became scholars themselves. When she died, numerous praise songs and poems were written in her honor. Several of them have been published in Dala al-Adib, an anthology of Saharan literature by Jamal Ould Al-Hasan. Fatima mint Shaykhna Buyahmed is the most celebrated of these learned women, partly because she lived in more recent times—from the late 19th through the mid-20th century. The daughter of a legal scholar who taught her Islamic jurisprudence, she so excelled in the study of the law that she occasionally wrote fatwas in the name of her father.

Jarfuna, by contrast, used her limited literacy to run her caravans, but she wasn't the only Masna woman to leave her mark as a businesswoman. Fatimatu mint Seri Niaba, for example, was a gifted 19th-century entrepreneur, as well as a learned individual. Although she did not leave any scholarly writings, Fatimatu, like many women of Tichit, earned her access to the caravan economy thanks to her literacy.

|

|

|

| Top: Smoothing each fragment of shell on a granite slab and carefully hand-drilling it with up to five holes, the women of Tichit have made beads a specialty. They trade their beads throughout Mauritania and into Mali. Above, left: Making couscous, among the most traditional staple foods not only in Mauritania but throughout North and West Africa, is a women’s culinary craft that can take up to two hours. Above, right: Yuma mint Bay weaves palm ribs and strips of leather to make a mat. |

Muslim women protected their property rights by keeping a paper trail of their commercial and civil affairs. They documented credit transactions and loan disbursements, and they wrote to men and other women with whom they conducted trade and exchanged market information. To be sure, only privileged and exceptional women—Fatimatu among them—acquired the skills necessary to make use of contracts and correspondence. Tichit depended on caravans to bring in limited supplies of writing paper, making that commodity relatively expensive. Not everyone could afford to engage directly in the caravanning economy at this level or, alternatively, to hire scribes.

Women were involved in Tichit's scholarly and caravanning activities in other ways, too, by crafting and ornamenting the leather bindings that protected manuscripts. The women of Tichit also made and decorated with colored dyes the cushions and small leather pouches that were among their primary export products. Indeed, there is a firm foundation for the popular Mauritanian proverb, “The woman is the man's trousers” (Limra' sirwal al-rajul), for it conveys the idea that a woman protects her husband and, by extension, their family.

Women were involved in Tichit's scholarly and caravanning activities in other ways, too, by crafting and ornamenting the leather bindings that protected manuscripts. The women of Tichit also made and decorated with colored dyes the cushions and small leather pouches that were among their primary export products. Indeed, there is a firm foundation for the popular Mauritanian proverb, “The woman is the man's trousers” (Limra' sirwal al-rajul), for it conveys the idea that a woman protects her husband and, by extension, their family.

The skilled labor of women and families was critical to the caravan economy of Tichit in both obvious and subtle ways. For one thing, women played an important role in manufacturing caravanning gear, such as water gourds, camel saddles, riding blankets and the leather pouches in which such goods as dates, lard and millet were transported. And they wove palm-tree fibers, grass and leather strips into the straps, bridles and quantities of cordage used to fasten down camel loads and harness caravans.

However, as Jarfuna illustrates, Tichit women also participated in the caravan trade directly. Falla mint Bubu and her husband, Khalifa Ould Al-Bashir, both now deceased, are a classic example of a 20th-century Tichit caravanning family. Almost every year, they left Tichit with their six children for three months on caravan. And Falla, a strong, warrior-like woman, often also went on caravan without her family.

|

| Built to endure years of use, camel saddles were often made and decorated by women, as were riding blankets and saddlebags. |

Typically, caravans from Tichit headed to Banamba, Nouara, Nara or Nioro, Malian markets on the southern edge of the desert. Falla and her family always went to Banamba. Caravanning families rarely traveled alone, preferring to join other families or groups for safety and support.

Falla's children, now in their late 30's to early 50's, describe a typical journey. “It took a full month to travel from Tichit to Banamba, the convoy walking without a break from morning to evening,” they recall. That regimen wasn't unusual. As Fatima mint Mbarak, another veteran caravanner, now a great-grandmother, explains, “We would go walking, walking, walking till the afternoon prayer or the evening prayer. We did not stop for lunch.” The caravan traveled from one well to the next, once going six days without replenishing its water supply, she adds.

“As soon as we stopped, we would unload the camels and start grinding the millet,” Falla's youngest daughter explains. “[The women and girls] made couscous with goat lard and tishdar [jerky, the caravanner's staple]. The next day we warmed up the leftovers for the morning meal.”

The daily routine was so intense there was no time to play. Falla's children recall sandstorms and strong winds, but not in detail. What they remember most vividly is the fast pace.

Caravanners usually walked alongside their loaded camels. But not the children: They had to run. The camel's average gait is six kilometers per hour (33/4 mph), a brisk walking pace for an adult human.

Caravanners usually walked alongside their loaded camels. But not the children: They had to run. The camel's average gait is six kilometers per hour (33/4 mph), a brisk walking pace for an adult human.

There was some respite for the children, however. When they got very tired, every couple of hours or so, they would climb aboard a moving camel, a move that called for great dexterity. One of Falla's sons recalls the agony he endured after scraping his kneecaps raw on the leather sacks of salt his camel was carrying.

|

| Ornamental leatherwork adorns what will become a usaada, or cushion. In the past, women used the same skills to decorate the leather bindings for manuscripts that are preserved in Tichit’s libraries. |

Caravans maintained a constant, rigorous pace to make it to the market in time for the end of the millet harvest in January, when prices were most favorable. Upon arrival, men and women traded salt for millet. Then the men took the camels to pasture while the women sold their leather products, beads and other goods. Some learned to speak the local Bambara language to barter more effectively in the marketplace; others got by with sign language (isharaat).

Female caravanners impressed their male counterparts, and today retired caravanning men never fail to recognize the women's contributions to their own training. “I first left on caravan as a young boy with my grandmother Ifna mint Qarba,” recounts Bayba Ould Bala, who is nearly 100 years old. One of the elders of Tichit, he is among the last speakers of Azer, the region's dominant language before it was supplanted by the Arabo-Berber language of Hasaniya. Similarly, Baba Ghazzar, now deceased, discussed how he learned the tricks of the caravanning trade from the women in his Masna family.

The caravans returned to Tichit with a range of supplies, including millet—the staple of the local diet—nuts, a variety of spices, wooden wares and cotton cloth, as well as slaves. Slaves quarried green and gray limestone and sandstone east of town for buildings. They also labored in the palm gardens, which produced one of the town's most valuable exports: dates.

|

| Now in her 80’s and a great-grandmother, caravanner Fatima mint Mbarak recalls stories of lost camels and the frightening few days during which her daughter became lost. |

Date cultivation was very labor-intensive, involving regular sand removal, desalination of leaves and replanting of palm tree shoots. A date-palm laborer could maintain a maximum of 10 trees at a time. Nowadays, date production in Tichit has lost its former glory as the oasis's population has fallen. A bad flood in 1999 led to a massive exodus westward to the town of Tijikja and to Mauritania's capital, Nouakchott. There are now fewer than 500 souls here, compared with more than 3000 before the deluge.

|

| Caravanners discuss plans for a salt caravan. |

One of the specialties of the women of Tichit and the neighboring village of Akreijit was crafting shell beads. In the past, the shells might have been collected locally, remnants of a former era when a green and lush Sahara boasted lakes and teemed with wildlife. In more recent times, the shells have been imported from the Atlantic coast.

Women and girls would sand small pieces of shell on a granite rock for hours to produce beads with the desired round shape, each taking several hours to fashion. Then they would carefully drill four or five holes into each bead with a bow-driven piercing tool. These beads (amjun) were an important item of exchange, highly prized in the markets of Mauritania and Mali by women who braided them into hairdos on such special occasions as weddings. Tahira mint Al-Khatabi, a seasoned caravanner, takes more than an hour to demonstrate the art of making a single amjuna.

Another export, a yellowish calcium powder called luwinkel, was collected in the nearby hills and sold for medicinal purposes. It was used to treat heartburn and indigestion, among other things. Today, every small shop in Tichit sells luwinkel by the kilogram.

|

| In Tichit, it is traditional for both boys and girls to become literate, mostly through education in the chapters (surahs) of the Qur’an. |

These stores also sell products brought in from Mali by caravan or truck via Ayoun el-Atrouss, a town some 200 kilometers (125 mi) to the south. These include a dozen different spices and special mixtures essential for cooking millet-grain couscous. Among them are taqiya, a mixture of herbs; simbala, another herbal concoction sold in cigar-shaped rolls; black pepper and “red pepper” kernels; and tajmacht—ground baobab-tree seeds used both to make a beverage and as a medicine. Goat butter or lard, onions, white and red beans, peanuts and dried meat are also part of this trade, which includes indigo dye and textiles produced from cotton grown and woven in Mali. Aside from foodstuffs and cloth, there are also platters made of woven grass and wooden utensils ranging from large mortars and pestles for grinding millet to receptacles for milking livestock, serving meals and drinks, and preserving dates.

Stories abound in Tichit about travelers nearly succumbing to thirst near a dry well, camels running away in the night and sandstorms wreaking havoc. Murjan mint Izidbih, a granddaughter of the venerated caravan leader Jarfuna, was 11 or 12 years old when she was accidentally abandoned. She was busy collecting gum arabic from thorny Acacia senegalensis trees—a resin used for a variety of purposes, from texturing milk beverages to starching cotton clothes—when she lost track of time. Before she knew it, the caravan had packed and departed without her. Only the next day did her family realize she was missing and immediately send several camel riders to find her. Meanwhile, Murjan had spent a frightful night in the wild. The following day, she met a nomad who sheltered her in his tent. It took seven days for the riders to locate her and return her to the convoy.

|

| Soueid Ould Mohamed Bouyatou, left, and Limam Ould Abdel Mu’min show manuscripts from their archive, one of some 20 archives and libraries in the oasis with writings that date to as early as the 12th century. |

Due to their menstrual cycles and fertility, caravanning posed special challenges to women. One woman explains how she was several months pregnant while on caravan late one winter season. On the return journey in the spring, the heat was so intense that she miscarried. She resolved never to join another caravan.

Fatima mint Mbarak remembers the crisis that beset several Tichit families on their return from Mali. Their camels, five teams totaling close to 80 head, strayed during the night, stranding the travelers. Since most caravanning families rented their camels from wealthier Tichit residents—Jarfuna, who owned a number of camels, was an exception—their disappearance put further stress on the members of the convoy. It took two weeks for men on foot to reassemble all of the scattered camels. “Praise God,” Fatima says, “that this happened when we were staying at a well.”

On December 22, 2009 a caravan composed of five men and 57 camels arrived in Tichit. It transported a mixed load of millet, rice—a staple that has recently gained ground in the local diet—and spices from Mali. The whole town was alerted, starting with Mohamedou Ould Hamar, the “guardian of the sabkhah,” or saltpan—a Masna in charge of supervising the salt harvest and tax distribution. Men and women immediately set to work, on their knees, scraping the surface of the lakebed. The next morning, each camel was loaded with four sacks of amersal salt weighing 50 kilograms (110 lb) each. With help from the locals, it took the five caravanners just over an hour to load the entire convoy, which immediately set off. The task was gracefully orchestrated in near-complete silence, save for the braying of the camels.

|

| With each of 57 camels bearing some 200 kilograms of salt, these caravanners from Ayoun paid the families of Tichit a total equivalent of about $128 for their cargo. As trucks come more often to Tichit, caravans are increasingly rare. |

Each camel-load of salt was purchased for 600 Mauritanian ouguiya or mro (the equivalent of $2.25), which was distributed among the three main clans of Tichit. The Shurfa and Awlad Billa each received one-quarter, and the Masna pocketed the rest, according to an arrangement dating back to colonial times. On top of this, a city tax of about $0.25 per camel-load was collected by the guardian of the saltpan.

In the 1960's, the average exchange rate, by weight, between millet and amersal salt was two to one. Today, profits are much narrower, according to the caravan leader Mohamed Ould al-Najim, a man in his 60's from Ayoun el-Atrouss. This is because caravans no longer travel all the way to Mali: Since 2006, a tarred road links Ayoun to the Malian market town of Nioro. Today, caravans organized by a handful of men travel only between Tichit and either Ayoun or Timbedra, a trip that averages 10 days one way.

In Ayoun, the salt is sold at the rate of 2500 mro per sack, or about $9.40. Thus, gross profits were about $35 per camel, or $1995 for the entire caravan. (Three of the 57 camels on this particular caravan belonged to women.) These figures do not include the costs of renting the camels and outfitting the caravan, or the profits realized from the loads transported to Tichit.

Caravans have long been the lifelines of the Sahara. But today, though Tichit remains largely “landlocked,” without a highway linking it to Mauritania's national road system, its dwindling population nonetheless relies less on caravans than on the diesel truck that regularly makes its way across the rough terrain from Tijikja, to the east, to replenish the town's supplies and carry out its primary exports: amersal salt and dates.

Throughout history, long-distance trade in Mauritania was a male profession. In Tichit, though, caravanning was not just a man's world. The wealthiest women of Tichit invested in caravan journeys by contracting family members and laborers, or sending slaves; women in the lower classes of society joined caravans themselves, for the most part accompanied by their husbands and children. Those women are remembered by all because of their leading role in planning, coordinating and directing camels, loads, supplies and family labor. This is why the story of Jarfuna, the remarkable woman caravan leader, lives on in the oral traditions of Tichit.

| |

Ghislaine Lydon is the author of On Trans-Saharan Trails: Islamic Law, Trade Networks and Cross-Cultural Exchange in Western Africa

(Cambridge University Press, 2009). |

|

Arita Baaijens (www.aritabaaijens.nl) is a photographer, writer and former environmental biologist who treks with her camels every winter in the Egyptian and Sudanese deserts. |