|

| massimo zanetti beverage usa (1886) |

Consider, for example, the figure of the white-bearded “Arab” that adorned the most popular brand in the country, Hills Bros, whose canisters lined the coffee shelf in nearly every American grocery in the early part of the 20th century: Standing in a flowing, full-length robe, wearing a turban more Indian than Arabian and “Aladdin” slippers with upcurled toes, “the Hills Bros Arab” strides into a deep swallow from an oversized mug that he holds in both hands. For a period of 50 years, he personified American coffee.

riginating in Ethiopia and Yemen, coffee had become a popular drink in Ottoman Turkey and parts of Europe by the second half of the 17th century, and was being grown extensively from Arabia to India and Java. In the mid-18th century, it began to emerge as an important cash crop throughout the New World regions where growers found the Arabica bean thrived, especially in the highlands of Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala and Mexico.

riginating in Ethiopia and Yemen, coffee had become a popular drink in Ottoman Turkey and parts of Europe by the second half of the 17th century, and was being grown extensively from Arabia to India and Java. In the mid-18th century, it began to emerge as an important cash crop throughout the New World regions where growers found the Arabica bean thrived, especially in the highlands of Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala and Mexico.

In the United States, the growing thirst for coffee roughly paralleled the nation's westward expansion and the changes that came with industrialization, immigration, and the rise of mass media and consumer society. By the second half of the 19th century, widely available, inexpensive coffee had become a staple in the growing numbers of urban homes and the diminishing numbers of farm families alike. By the turn of the 20th century, the expanding coffee industry began to brew up marketing incentives to further stimulate sales, and to develop arrays of gadgets and merchandise designed to enhance the experience of coffee-making and coffee-drinking: special storage cans, grinders, percolators and sets of mugs and cups to fit any occasion.

These, like coffee itself, were promoted through advertising. This put coffee on the radio, on billboards and street signs, in magazines and, after World War ii, on television. To appeal to the largest number of people, advertisers pitched their product to the “average American,” and their success showed in the drink's colloquial nickname: “a cuppa joe,” a tag that marked coffee as something that was as “all-American” as “the average Joe.”

Buttressing this business of coffee were the merchants and companies trading and transporting beans north from Central and South America. Their endeavors were supported by reliable maritime shipping and airtight (later vacuum-packed) metal-canister technology. In the economic ferment of the time, hundreds of companies flourished, and several family-owned establishments rose to the top.

|

|

|

|

|

|

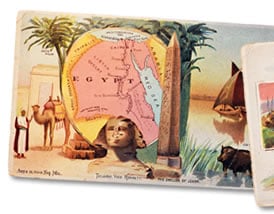

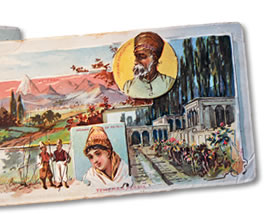

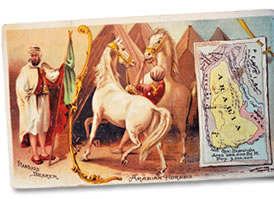

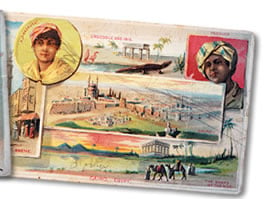

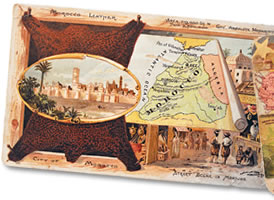

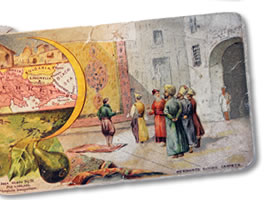

| Beginning in the 1890’s, Arbuckle Bros. began to entice buyers by including in its packages of coffee peppermint sticks, discount coupons and hundreds of trading cards. Three sets of geographical cards included 21 that depicted Arab and Middle Eastern lands. |

|

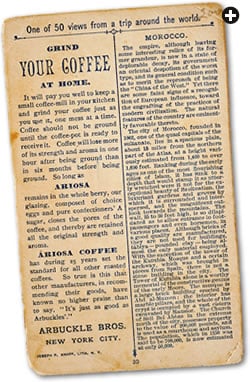

| The back of each Arbuckle’s card described both the product and the orientalist scenes on the front of the card. |

Arbuckle Bros. emerged as one of the earliest companies to establish a brand name that earned coast-to-coast popularity. In Pittsburgh, John and Charles Arbuckle in 1865 patented a method of preserving the taste and aroma of roasted coffee beans by coating them with a glaze of egg white and sugar. Their coffee was then packaged mechanically and sealed in airtight bags that sported the bright yellow and red colors of Arbuckle's lead brand, Ariosa. As a marketing incentive, each Ariosa bag also contained (and still contains) a peppermint stick. In the 1890's, Arbuckle coffee packages began offering coupons redeemable for “all manner of notions including handkerchiefs, razors, scissors and wedding rings,” as well as several series of trading cards that depicted countries and peoples of the world, state maps, famous paintings, flowers, animals, children and religious scenes. Arbuckle's became especially popular in the West, where it became known as “Cowboy Coffee”—a term the company still uses in its advertising today.

In three of Arbuckle's 50-card series—“National Geographical,” “Views from a Trip Around the World” and “Sports and Pastimes of All Nations”—there appeared 21 cards themed to Middle Eastern countries and cities. The front of each card shows a color-lithograph scene, rendered according to the tastes of the time, and the back provides basic information about the scene, also in a manner reflective of the era. (For example: “Turkey—Area: 63,800 square miles; Population: 4,490,000; Government: Absolute Despotism” and “Cairo: The streets are highly picturesque with gaily dressed traders, dragomans, mountebanks, dogs, donkeys and snake-charmers.”)

True to this popular, orientalist view of the Middle East in general and of Arabs in particular (who were often not distinguished from Turks, Persians or other groups), it was not unusual to see ancient Assyria and ancient Judea mixed among the modern nations, a consequence of the casual blurring of ancient and modern that made up a “timeless” view of the Middle East that can still be found today.

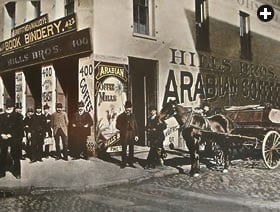

y the late 19th century, Chicago had grown into a national hub of industry, commerce, and the ship and rail transport systems that distributed coffee nationwide. It was around this time that the marketing of coffee using Middle Eastern brand names and images peaked. Family-owned companies like Continental Coffee thrived in Chicago, supported by local manufacturers of vacuum-sealed metal cans such as General Can Company, which also produced red-and-white canisters for the Rust-Parker Company's brand, Omar. Competitor American Can Company produced vividly decorated containers for Baghdad Coffee. To the east in Toledo, Ohio, the Blodgett-Beckley Co. brought to market Arabian Banquet, which boasted, on a canister displaying an “Arab warrior,” that “We guarantee the absolute genuineness and purity” of the blend.

y the late 19th century, Chicago had grown into a national hub of industry, commerce, and the ship and rail transport systems that distributed coffee nationwide. It was around this time that the marketing of coffee using Middle Eastern brand names and images peaked. Family-owned companies like Continental Coffee thrived in Chicago, supported by local manufacturers of vacuum-sealed metal cans such as General Can Company, which also produced red-and-white canisters for the Rust-Parker Company's brand, Omar. Competitor American Can Company produced vividly decorated containers for Baghdad Coffee. To the east in Toledo, Ohio, the Blodgett-Beckley Co. brought to market Arabian Banquet, which boasted, on a canister displaying an “Arab warrior,” that “We guarantee the absolute genuineness and purity” of the blend.

But it was in San Francisco in 1878 that Austin and Reuben Hills purchased the Arabian Coffee & Spice Company, and they made Hills Bros into one of the longest-lasting purveyors of coffee in America. Integral to the company's success was the “Arab gentleman” image that became its brand up through the 1950's. So iconic did he become that, today, the company has commemorated him with a bronze statue at the entrance of its old factory. The plaque on the statue's base states: “In 1900, when Hills Bros originated the process for vacuum-packing coffee, this trademark appeared on the first Hills Bros coffee can. It has lived on through all the years as a lasting symbol of coffee quality.”

Not far behind, MJB coffee, whose 1904 brick factory still stands not far from Hills Bros', adopted the legendary Aladdin himself as a trademark. However, he did not last as long as Hills Bros' gentleman.

Not far behind, MJB coffee, whose 1904 brick factory still stands not far from Hills Bros', adopted the legendary Aladdin himself as a trademark. However, he did not last as long as Hills Bros' gentleman.

In Los Angeles, Coffee Products of America, Ltd. launched the brand Ben Hur, sold in a red can decorated with images of the chariots familiar to Americans who had read the enormously popular Lew Wallace novel or who had seen the silent-screen classic films

of 1907 and 1925.

Considering the tonnage of coffee that was coming to the United States from Latin America and the abundance of orientalist images concocted by American businesses to sell their products—Palmolive, for example, used images of “ancient Egyptian beauties” to sell its soaps and lotions—it is not surprising that in 1919, when the Atlantic and Pacific Company (A&P) branded its nationwide coffee “Bokar”—a name that combined the Colombian cities of Bogota and Cartagena—it, too, looked to the allure of the Middle East for its brand imagery: a camel caravan in silhouette. Similarly, America's first decaffeinated coffee, Sanka, employed a Hills Bros—like image of a bearded (and of course turbaned) “Arab” graciously pouring coffee from a curved-spout pot. This long-standing trademark appeared from the 1920's through the 1950's on the bright orange Sanka Coffee label. Today, although the “Arab” is gone, the color orange has come to be associated generically with decaffeinated coffee.

|

|

As a chapter in the history of both coffee and America, these Middle Eastern representations did their job: They sold coffee—lots of it. Crafted by illustrators and graphic designers who drew from the pages of popular imagination, the images struck romantic chords in America's rapidly urbanizing, increasingly pragmatic population, and the brands were part of the broader, more widespread fashion of “Arab,” “Middle Eastern” and “Egyptian” images that appeared everywhere, from the illustrated bestseller 1001 Nights to the 1893 Chicago Columbian Exposition's “authentic” Middle Eastern cultures and rituals—among them a coffee ceremony. Theaters showed movies like “The Sheik” and “The Mummy”; the musical “Desert Song” was a hit, as was the 1924 George Gershwin tune “Night Time in Araby.” Associated with all were illustrated film posters and colorful sheet-music covers. Pulp fiction magazines (Argosy, Fantastic Adventures and Oriental Tales were three) portrayed the Middle East as a land of exotica, adventure and intrigue.

his all began to change after World War ii, when corporate food conglomerates such as Procter & Gamble, Sara Lee and Kraft Industries began to buy up the family-owned coffee distributors and rebrand them with streamlined, “modern” looks. Largely gone were the turbaned “Arabs”—although the camel caravan has held on to this day as an occasional motif.

his all began to change after World War ii, when corporate food conglomerates such as Procter & Gamble, Sara Lee and Kraft Industries began to buy up the family-owned coffee distributors and rebrand them with streamlined, “modern” looks. Largely gone were the turbaned “Arabs”—although the camel caravan has held on to this day as an occasional motif.

|

| In 1990, Hills Bros adopted a new “taster” figure designed to evoke its turn-of-the-century American founders. |

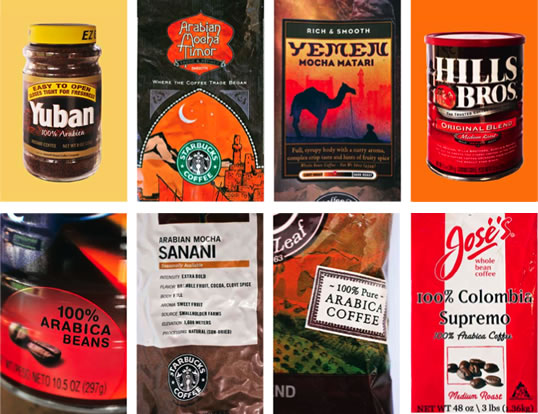

According to the National Coffee Association, today one in five American adults, and one in two young adults, drinks coffee daily. Advertising and marketing still play their role in today's increasingly dominant “coffeehouse culture,” led since the 1980's by Starbucks, which opened its first Seattle café in 1971. Even though “the Starbucks factor” may appear to be turning America's diner-based, proudly egalitarian “cuppa joe” into a thing of the past, a closer look at Starbucks and its competitors shows that while appeals to elitism can drive up prices—and, presumably, profit margins—exoticism and Arabian origins are still useful marketing tools.

“Exotic and refined” is how Starbucks begins to describe the coffee in its packages of Arabian Mocha Timor, a blend first released in 1996. It goes on to promise “a delicate balance between the spicy and berry notes of Arabian Mocha Sanani and the smooth, clean finish of East Timor.” This blend was sold in packages bearing the same fiery, earthy colors that have enticed consumers to coffee for more than a century—reds and browns. Similarly, bags of Starbucks' Arabian Mocha Sanani (cultivated around Sana'a, the capital of Yemen) advise that the crop was grown at an elevation of 1600 meters (5200') on smallholder farms, and sun-dried. Not to be outdone, The Coffee Bean & Tea Leaf, established in 1963, sells Yemen Mocha Matari (“full, syrupy body with a nutty aroma, complex crisp taste and hints of fruit, spice…and chocolate”). Among the silver and black packages from the gourmet chain Dean & Deluca is the Sahara Blend that “honors the ritual of coffee that still flourishes in cities along the ancient spice routes.” And on the same shelf stand bags of Mocha Java Blend, which is “impeccably balanced with sweet layers of chocolate, apricot and tobacco,” embodying “coffee's most storied and delicious traditions.”

Today words, not images, lure would-be drinkers with exotic, romanticized motifs that are as timeless as the imaginings of American orientalism. And while, these days, marketing focuses on the drinker's personal experience, promoting a kind of armchair-tourism gastronomy, or an “exoticism of one's own senses,” yet many brands—among them such remaining pillars of the “cuppa joe” tradition as Yuban, Maxwell House and Nescafé—label their products “100% Arabica” to serve notice to the buyer that the product will have a dependably smooth taste, one whose pleasures hark back to coffee's heavily storied origins.

Whether it's an old-timer's “cuppa joe” served by an imagined stereotype wearing a robe, or instead a double grande latté frappucino made from the hour's brew of Yemen Mocha Matari, the American coffee industry continues to harness Middle Eastern representations to help Americans buy and enjoy one of the most popular drinks in history.

|

Jonathan Friedlander (friedlander.jonathan@gmail.com) is a photographer, author and collector of Middle Eastern Americana. Formerly assistant director of the Center for Near Eastern Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles, he is affiliated with the Department of Special Collections at the university’s Young Research Library. His trove of Middle Eastern Americana can be accessed via the Online Archive of California at www.oac.cdlib.org. |