|

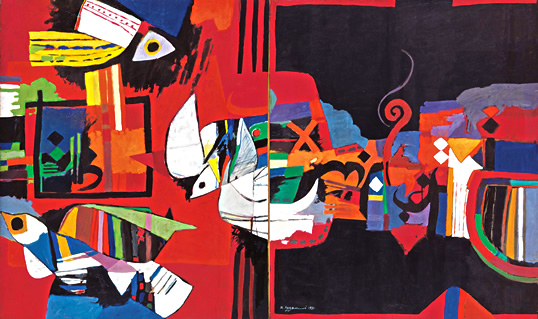

| Dia Azzawi, “Red Sky with Birds,” 1981. |

|

n the mid-1980’s, when Shaykh Hassan Ali Al-Thani began studying art history at Qatar University, he was struck by the fact that no Arabs figured in the story of modern art. He decided to look deeper.

n the mid-1980’s, when Shaykh Hassan Ali Al-Thani began studying art history at Qatar University, he was struck by the fact that no Arabs figured in the story of modern art. He decided to look deeper.

|

| RICHARD BRYANT |

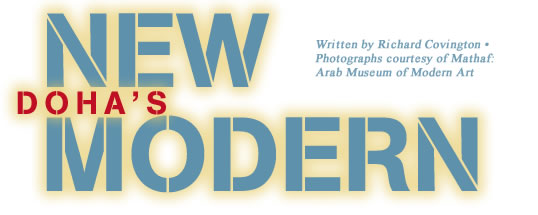

| Taheya Halim installation, 1960’s. |

|

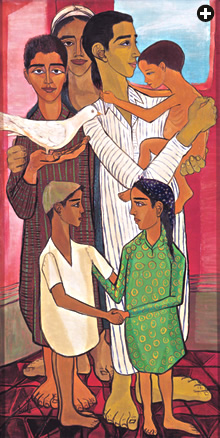

| Gazbia Sirry, (title unknown), 1955. |

With the help of his professor, the painter Yousef Ahmad, the shaykh, a member of Qatar’s royal family, embarked on what became an enduring exploration into the lives and labors of contemporary Arab artists. In short order, he was deeply bitten by the urge to collect their artworks.

“I realized that modern Arab art was in a terrible state,” he explains. “There were very few galleries in the region, and neither the gallery owners nor the artists themselves had a true appreciation of the value of the work.”

Speaking in his 10th-floor office overlooking Doha harbor and the sand-colored, cubist blocks of the I. M. Pei–designed Museum of Islamic Art, the 50-year-old Hassan, now the vice chairman of his country’s museum authority, recalls that his passion for acquiring Arab modern art first met with bafflement. “People thought it was very strange that I would put so much time, energy and money into collecting pictures,” he says. “I realized that if I started to put some of these pieces on display, they would begin to understand how this art is a connection to our past and a vision for our future.” The idea for a museum devoted to modern and contemporary Arab artists was born.

|

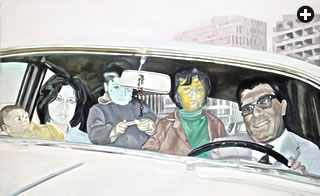

| orlando thompson |

| Shaykh Hassan Ali Al-Thani and Yousef Ahmad, photographed at Mathaf’s opening in December. |

By becoming a hands-on patron of the arts, Hassan, a former painter and still a photographer and videographer, is helping transform Qatar into a cultural hub in the Gulf region. His collection of some 6300 artworks, acquired since 1986, is the most extensive modern Arab art collection in the world.

Opening last December, the collection’s new home, called Mathaf (Arabic for “museum”), is both a modest and a serious affair. Housed in a two-story converted school near Education City, the sprawling enclave of mostly American university campuses a half-hour’s drive from Doha’s skyscrapers, the fledgling institution eschews the glamorous aura surrounding such other museum projects in the Gulf as the satellites of the Louvre and the Guggenheim rising on Abu Dhabi’s Saadiyat Island. The low-key design by French architect Jean-François Bodin is, Hassan explains, a temporary home, as plans for something more permanent—and presumably larger--are still under discussion. In addition to Mathaf’s galleries, the building includes a café, a small bookshop, a library and a classroom, all intended to help fulfill the museum’s ambition to become a center for research and education.

The name of Mathaf’s inaugural exhibition, “Sajjil: A Century of Modern Art,” was inspired by a poem by the Palestinian author Mahmoud Darwish: Sajjil is Arabic for “the act of recording.” In the show, some 236 works, arranged in a dozen airy, white-walled galleries, offer up a survey of Hassan’s collection, starting from its oldest work, a small oil canvas from 1847 by Ali Zara, depicting a covered alley in Cairo.

Critical reaction to “Sajjil” has ranged from praise of innovators like Gazbia Sirry, Ramsis Younan, Ibrahim el-Salahi, Hamid Nada and Mahmoud Said to questions about whether it all goes far enough. “Nothing was censored,” says Mathaf’s acting director and chief curator Wassan al-Khudairi, referring mostly to works of political commentary, as well as a smattering of nudes.

Critical reaction to “Sajjil” has ranged from praise of innovators like Gazbia Sirry, Ramsis Younan, Ibrahim el-Salahi, Hamid Nada and Mahmoud Said to questions about whether it all goes far enough. “Nothing was censored,” says Mathaf’s acting director and chief curator Wassan al-Khudairi, referring mostly to works of political commentary, as well as a smattering of nudes.

Alongside “Sajjil,” two complementary exhibitions opened in a cavernous annex of the city’s Museum of Islamic Art. “Interventions” presents early productions by five artists represented in the shaykh’s collection together with the same artists’ fresh creations produced for Mathaf’s opening. More daring is “Told/Untold/Retold,” which shows new commissions of visual narratives by 23 young Arab artists living across the region and in Europe and the United States.

In a region with little tradition of appreciating, collecting and exhibiting modern art, nearly everything about Mathaf is groundbreaking. Although there is a growing roster of regional art fairs, auctions and commercial galleries, what has been missing, al-Khudairi observes, are institutions. “If you see pictures in isolation at an auction or in a catalogue, they don’t mean anything,” she continues. “What we want to do is to establish a context, a history, so you can make connections among works.”

|

| Jorell Legaspi |

| “What we want to do is to establish a context, a history, so you can make connections among works,” says Wassan al-Khudairi, Mathaf’s acting director and chief curator. |

Compiling biographical information on the 118 artists represented in “Sajjil,” and then editing it into a 374-page Arabic and English-language catalogue, proved to be a task in itself. Al-Khudairi and other researchers relied on gallery owners, collectors, the artists themselves, their families and descendants to assemble the often elusive personal histories. “Now, from the bios, you can see who studied where and with whom, and you can start to make key connections,” the director explains as we sit over coffee in the museum’s sun-drenched café.

“One thing we are trying to demonstrate is how Arab artists were part of mainstream art,” she says. “Many studied in Paris, Rome and elsewhere and became engaged participants in the modern-art movement. They came home and started schools or just had their own studios, and their influence spread to other artists,” she continues.

Unlike western modernists, Arab artists were not rebels, al-Khudairi argues. Instead of rejecting European or Arab traditions, she says, they sought a blend that brought European points of view and techniques to Middle Eastern subjects.

Unlike western modernists, Arab artists were not rebels, al-Khudairi argues. Instead of rejecting European or Arab traditions, she says, they sought a blend that brought European points of view and techniques to Middle Eastern subjects.

Like many of the modern Arab artists she exhibits, the 28-year-old art historian herself has a background that mixes East with West. Growing up in Kuwait with Iraqi-born parents, she studied art history in Egypt, the us and the uk, and she worked at Atlanta’s High Museum of Art and the Brooklyn Museum of Art before signing on in September 2007 to direct Mathaf.

Petite and dynamic with wavy black hair, al-Khudairi relishes her pioneer role. “There is certainly a buzz surrounding modern Arab art,” she declares. “People want to try to understand the ‘mysterious’ Arab world through its art.

|

| Jeffar Khaldi, from “Fade Away,” 2010. |

“The Gulf is misconceived as having no history, so when people hear about a collector who’s been gathering works for 25 years, and hear that we’ve built a modest-sized museum designed by a great architect who is not a ‘starchitect,’ we catch them off-guard.”

Although Mathaf has only been open a matter of months, the museum has already hosted two conferences for international art scholars; another is planned for December. Art from Mathaf has been lent to shows in the us, Germany and France. Emerging poets have written and recited compositions inspired by objects in the collection, films have been shown, and student volunteers from nearby universities have devised personalized tours of their favorite items. “The idea is that if these 19-year-old and 20-year-old college students speak to teenagers, they’re more likely to listen,” al-Khudairi explains.

To Yousef Ahmad, 55-year-old professor and painter, Mathaf is unique in its focus on Arab modern artists from the region as a whole. Other museums of modern art in the Arab world, he notes, tend to focus primarily on national artists.

Ahmad started his own career at the art academy in Cairo, a venerable institution that opened in 1908. Following in the footsteps of many aspiring Middle Eastern painters, he went west to continue his education, but not to Paris, Rome or London: He landed at the California Institute of Art in Oakland, where he earned a master of fine arts degree in 1982.

Back in Doha, he began teaching art history and drawing at Qatar University. Hassan was one of his star pupils and soon became a close friend and patron: Among the first canvases Hassan acquired was Ahmad’s own 1976 abstract work “Construction,” which now hangs in the museum.

Under his former professor’s tutelage, Hassan learned all he could about Arab artists, consulting reviews, conversing with other collectors and visiting the artists themselves. It was often frustrating, he recalls. Few books had been written about the artists or the region’s artistic movements. Newspaper and magazines, he says—including Aramco World and Saudi Aramco World—were about the only published sources available.

“I went to Egypt, Lebanon, Morocco,” Hassan recalls. “Sometimes I would stay with the artists and sometimes they came to Doha,” he adds.

One place Hassan was unable to visit was Iraq, but in 1990 Ahmad was able to arrange for some 400 works by Iraqi artists to be transported from Baghdad to Doha in 40 trucks. Among the works was an antic street scene by Jewad Selim entitled “Baghdadiat” that is in the current show. In 1994, after nearly eight years of collecting, Hassan opened a private museum in a pair of villas that he had converted into gallery spaces and artists’ studios. Ahmad became the director.

|

| Jassim al-Zainy, “Features from Qatar,” 1973. |

Around 1995, as Baghdad under sanctions became a difficult place for artists, Hassan invited Dia Azzawi, Ismail Fattah, Mahmoud al-Obaidi and other Iraqi painters to take up residence in the studios of the villa museum.

“I gave them space, canvases, paint and other materials and turned them loose,” recollects Hassan. Sketching with the artists and photographing them, he became more of a colleague than a patron. The loosely organized collective provided a productive refuge for a decade, until around 2005, when Hassan decided to close it. The artists moved to the us, Canada and Europe. Of the 500 or so works that were produced during these informal villa residencies, a dozen are currently on display at Mathaf.

Meanwhile, Hassan and Ahmad continued methodically scouring the region for finds. To some artists, the shaykh’s support meant the difference between obscurity and recognition. Mounir Canaan, for example, was a successful magazine illustrator in 1940’s Cairo. He sank into poverty in the 1950’s and 1960’s when he began producing abstract collages made with scraps of wood, cardboard, jute and glued sand. “His efforts were not only misunderstood, they were reviled,” the shaykh explains. Hassan began buying Canaan’s art, and he recommended it to the Arab World Institute in Paris, which also made several purchases.

“Canaan wrote to me that, for the first time in his life, he could afford to buy a studio,” Hassan reflects. On the artist’s death at age 80, in December 1999, the shaykh acquired the entire contents of that studio. Canaan is now regarded among the most important artists in the Arab world.

|

| Khalil Rabah, from “BIPRODUCT,” 2010. |

Frequently, too, artists and their families balked at parting with treasured pieces. But when they learned that Hassan planned on showing them in a public museum, they often agreed after all.

A pyramid 233 centimeters tall (7' 6"), made of wood and crawling with images of creepily realistic ants, is a striking case in point. Constructed in the 1960’s by Cairo artist Taheya Halim, the installation sculpture generated confusion when it was first unveiled. “Back then, people didn’t know what to make of it,” jokes Hassan. “They thought it was some sort of decorative backdrop for a store window. But when I saw a photograph of it in the mid-1990’s, I said to myself, ‘I must have it for the museum!’”

Halim, who was then 85 years old and one of the established doyennes of Arab art, refused Hassan’s initial purchase offer, saying she had promised the piece to the Cairo museum. But when he assured her it would have pride of place in the larger institution he was planning, she changed her mind. The piece, which some critics have interpreted as a veiled attack on the controversial construction of the Aswan High Dam (with the ants representing exploited laborers), is now showcased in the Mathaf’s galleries of abstract and conceptual art.

Ultimately, Hassan’s ambitions outgrew his resources. In 2004, he persuaded Shaykha Mozah Al Missned, the second wife of the Qatari emir Shaykh Hamad bin Khalifa Al-Thani, to place his collection under the auspices of the Qatar Foundation.

Now, in addition to lending art for exhibitions abroad, Mathaf is conserving and restoring modern artworks and building up a research center as a scholarly source of information on artists, art schools, galleries and commercial sales in the region, starting with Hassan’s own library of some 7000 books on art—including a growing number of publications and catalogues focusing on the Middle East. He hopes to produce an encyclopedia of Arab art that will be available over the Internet.

“We’re becoming an international player, not just an institution for Qatar,” he says.

|

Paris-based author Richard Covington (richardpeacecovington@gmail.com) writes about the arts, culture, history, archeology and science. His article “Roads of Arabia,” about Saudi Arabian archeology, was the cover story of the March/April 2011 issue. Previously, he has reported for Saudi Aramco World from Istanbul, Dhaka, Karachi, Venice, Tashkent and Almaty. |