|

|

| |

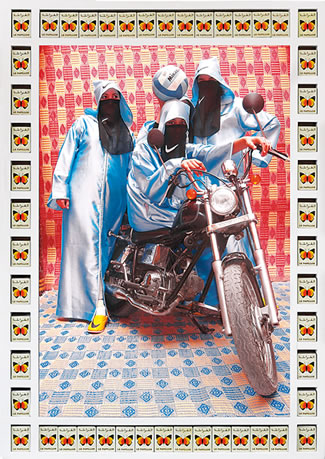

Hassan Hajjaj, “Nikee Rider,” 2007. Courtesy of the artist and Rose Issa Projects. |

iddle Eastern artists, whether they live in that culturally kaleidoscopic (and ill-defined) region or outside it, are at the center of one of the world’s most dynamic movements in contemporary art.

iddle Eastern artists, whether they live in that culturally kaleidoscopic (and ill-defined) region or outside it, are at the center of one of the world’s most dynamic movements in contemporary art.

|

| Leila Essaydi, “Les Femmes du Moroc #7,” 2005. Courtesy of the artist and Waterhouse & Dodd. |

|

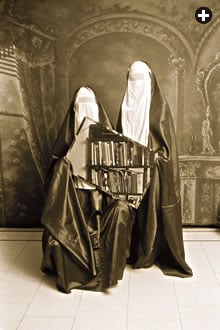

| Shadi Ghadirian, from “The Qajar Series,” 1998-1999. Courtesy of the artist. |

Their work is suffused by themes of identity, memory, grief, rage and a sense of belonging to ( or alienation from) the place or culture in which they live. The traumatic ruptures of wars, exile and migration that have affected them all are partly responsible—but a different consciousness has emerged in the last few years. What’s new is a cultural confidence and optimism, stemming from the fact of survival and the rising expectations that go with global recognition of the quality of their art.

“Everybody thinks we’re crying all the time!” says Rose Issa, a curator of Iranian–Lebanese background whose London exhibitions have given visibility to Middle Eastern artists for 25 years. “But our art is not only about despair. It’s about beauty too—the beauty of ordinary people’s lives, enabling destruction to become hope. The artists who interest me now communicate, fun, color, joy, love.”

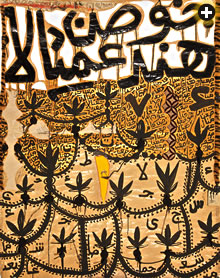

She points to the photographs of Hassan Hajjaj, a young Moroccan–British artist who captures upbeat rhythms of North African street life in an iconographic style that radiates both warmth and kitschy self-mockery, and who says, “I wanted to express so-called Arab work in a cool way.”

That sensibility, says Issa, is what the new “Mideast cool” is about: playfully questioning stereotypes and exploring the relationships between traditions and modernity, between “Easts” and “Wests.”

ncreasing numbers of galleries in top art centers like London, Paris and New York are exhibiting contemporary Middle Eastern art. At Sotheby’s and Christie’s, the world’s top auction houses, sales of contemporary Middle Eastern art are now regular, hugely successful events that—even during the current recession—generate an upward spiral of record-breaking prices. What’s behind it?

ncreasing numbers of galleries in top art centers like London, Paris and New York are exhibiting contemporary Middle Eastern art. At Sotheby’s and Christie’s, the world’s top auction houses, sales of contemporary Middle Eastern art are now regular, hugely successful events that—even during the current recession—generate an upward spiral of record-breaking prices. What’s behind it?

To generalize broadly, although contemporary Middle Eastern art is often challenging and iconoclastic, it is nonetheless often esthetically beautiful, and rarely either nihilistic or self-indulgent. There’s fire, there’s passion, there’s confidence in its messages and its own self-worth. “It reflects the reality of what’s going on in the Middle East,” says Dalya Islam, deputy director of Sotheby’s Middle East department. “It’s thematically relevant, addressing the issues of today.”

Venetia Porter, curator of the British Museum’s Middle East department, adds, “Many artists of the region have kept alive an avant-garde culture in the arts. In many cases, this has sadly required personal sacrifices, including emigration and persecution, but it is these artists’ perseverance that has allowed a greater level of understanding of the cultural achievements of the contemporary Middle East, at a time when such understanding is needed more than ever.”

Nat Muller, first curator of Cairo’s Townhouse Gallery and author of Contemporary Art in the Middle East (2009), writes that, throughout the Middle Eastern region, “artists take on many roles: witness, archivist, architect, activist, critic, cartographer, storyteller, facilitator, trickster, dreamer.” And they often do so as citizens of two—or often more—cultural worlds. This gives artists a keen awareness of their own multiple layers of identity and experience.

|

| Sara Rahbar, “Flag #19” from the series “Memories Without Recollection,” 2008. Courtesy of Saatchi Gallery. |

|

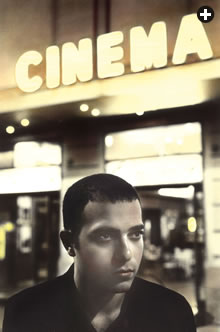

| Youssef Nabil, “Cinema, Self-portrait, Florence,” 2006. Courtesy of the artist and The Third Line. |

Amid this diversity, four common characteristics of Middle Eastern contemporary art stand out: beauty, craftsmanship, meaning and spirituality. These go beyond time and place, and for viewers of Middle Eastern background as well as others, they help make the art extraordinarily satisfying and inspirational.

In every time and place, people hunger for beauty. Much contemporary Middle Eastern art offers a quiet, often minimalist elegance. Many of the same shapes that characterize classical art from the region—especially geometric and calligraphic ones—deeply inform contemporary works. Likewise, today’s contemporary artists have embraced the craftsmanship that is highly valued in classical Middle Eastern art. From painting and sculpture to photography, video, digital images, installations and performance art, technical excellence prevails.

Meaning comes from connections to concerns, hopes, experiences, questions and dreams shared by artist and viewer. Because contemporary Middle Eastern artists are asking questions and making statements about society, their works are rarely entirely abstract, and often tend toward the figurative and the narrative. “The notion of ‘art for art’s sake’ is inconceivable in the Arab world,” writes Nada M. Shabout, director of contemporary Arab and Muslim studies at the University of North Texas. “Works of art are texts both for art and society.”

Finally, artists are often aware that greatness in any of the arts is about transformation. In this regard, the contemporary development of calligraphic art is particularly inspiring: It can cause the spirit to soar, even if the viewer does not read Arabic. Elisabeth Lalouschek, artistic director of London’s October Gallery, which exhibits top contemporary calligraphers like Hassan Massoudy, Wijdan Ali and Rachid Kouraichi, says, “I like the fluidity, the breadth, the airiness, the elegance of calligraphy. It’s very spiritual.”

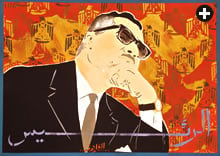

ow have traditional Arab, Persian, Turkish, North African and Central Asian arts grown into the defiantly modern presence of a new Middle Eastern cool, with its emphasis on the upbeat and a style in which a nod to fashion can lighten underlying pain? How are these artists in dialogue with their pasts, both ancient and recent? Of Egyptians, Muller observes that “articulations of the contemporary … are weighed down by an epic Pharaonic past and an equally epic dream of … modernity and independence.” One leading explorer of this dialogue is Egyptian artist Chant Avedissian, who draws on Pharaonic design motifs, hieroglyphs, the craftsmanship of Islamic urban centers and popular Egyptian posters and magazines. He combines them all in highly crafted photographs, producing images that probe the visual languages of consumerism and political propaganda. His critically acclaimed series “Icons of the Nile” (1991–2004)

ow have traditional Arab, Persian, Turkish, North African and Central Asian arts grown into the defiantly modern presence of a new Middle Eastern cool, with its emphasis on the upbeat and a style in which a nod to fashion can lighten underlying pain? How are these artists in dialogue with their pasts, both ancient and recent? Of Egyptians, Muller observes that “articulations of the contemporary … are weighed down by an epic Pharaonic past and an equally epic dream of … modernity and independence.” One leading explorer of this dialogue is Egyptian artist Chant Avedissian, who draws on Pharaonic design motifs, hieroglyphs, the craftsmanship of Islamic urban centers and popular Egyptian posters and magazines. He combines them all in highly crafted photographs, producing images that probe the visual languages of consumerism and political propaganda. His critically acclaimed series “Icons of the Nile” (1991–2004)

|

| Installation at Arabicity of 100 stencils from Chant Avedissian’s 1991-2004 series “Icons of the Nile.” Courtesy of Rose Issa Projects. |

|

| Chant Avedissian, “El Raiis” (Nasser) |

|

| Houria Niati, “Mother and I,” from the series “Curtains of Words,” 2006. Courtesy of the artist. |

Iraqi-born Leila Kubba Kawash refers to ancient Sumerian culture as well as Greek and Islamic cultures to “piece together different time periods, … to find a place where the past and present overlap.” More directly contemporary is Iraqi Himat Mohammed Ali’s moving memorial of 12 books of Arabic script overlaid with photographs and blotched with patches of black and red paint in commemoration of a car bombing on Al-Mutanabbi Street, which since the 10th century has been the center of Baghdad’s book trade.

For Iranian artist Farhad Moshiri, the recent past includes eight years of the Iran–Iraq war, which helped inspire his installation of 1001 toy guns covered with gold leaf. This came as a new direction for an artist best known for his images of classical Iranian ceramics, many embellished with Farsi calligraphy, presented on huge white canvases that united the traditional with the contemporary. (In 2008, Moshiri became the first Iranian artist to sell a work for more than one million dollars: “Eshgh (Love),” a calligraphic work on canvas, was spattered with glitter and Swarovski crystals.)

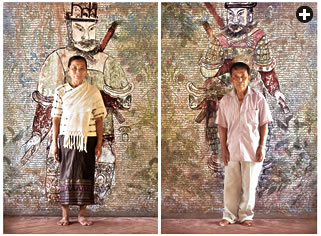

In Iran’s not-so-distant past, the Qajar dynasty, which ruled from 1794 to 1925, often used portraiture for political propaganda, and yet there was always a yearning for prettiness, often evoked in flower paintings, as well as an abstract, spiritual dimension conjured up with mirror mosaics during that period. Childhood memories of the elaborately mirrored throne room in Tehran’s Golestan Palace are imprinted on artist Monir Farmarmaian’s mind, and these have inspired her 40 years of achingly poetic installations in mirrored mosaic, which also allude to the search for the spiritual inner self.

In Iran’s not-so-distant past, the Qajar dynasty, which ruled from 1794 to 1925, often used portraiture for political propaganda, and yet there was always a yearning for prettiness, often evoked in flower paintings, as well as an abstract, spiritual dimension conjured up with mirror mosaics during that period. Childhood memories of the elaborately mirrored throne room in Tehran’s Golestan Palace are imprinted on artist Monir Farmarmaian’s mind, and these have inspired her 40 years of achingly poetic installations in mirrored mosaic, which also allude to the search for the spiritual inner self.

|

| Fathi Hassan, “Life,” 2009. Courtesy of Rose Issa Projects. |

|

| Laila Shawa, “Desert City,” 2008. Courtesy of the artist and Articulate Baboon Gallery. |

Near the end of the Qajar period, photography became the court’s medium of choice for portraiture. Contemporary Tehran photographer Shadi Ghadirian draws on these conventions in her “Qajar” series of sepia-toned photographs. Each shows one or more female models theatrically posed in vintage attire against period backgrounds, and to each Ghadirian added incongruously modern items, such as sunglasses, a vacuum cleaner or a can of Pepsi.

“The jarring contrast,” writes Marta Weiss, curator of photographs at London’s Victoria & Albert Museum, “is indicative of the tension between tradition and modernity, public personas and private desires, that many Iranian women navigate on a daily basis.” Ghadirian’s spirited debates with social issues that concern and inspire her inform her other series as well, which blur the distinctions between documentary and fiction, often wrapping needle-sharp points in dry humor. Probing the limits of her expressive freedom, she continues to live in Iran despite artistic residencies that have been offered to her from western institutions. In doing so, she mirrors her generation, the first since the 1979 Islamic Revolution, asserting its place despite doing so largely behind closed doors.

Equally witty, winking at tradition and subversively questioning stereotypes, is photographer Hajjaj, who lives in both Marrakesh and London. He delights in street style and mash-ups of traditional culture and global branding. His models, dressed in veils and djellabahs, seem to take pride in their heritage, but add their own generational stamps, such as the veil and headscarf sporting an imaginary Louis Vuitton logo and the babouches displaying a Nike swoosh. As Issa says, the street-smart figures “sometimes look menacing, but they are simply defending their world, their turf, their style and their right to have problems and aspirations. Like the artist, they have guts and attitude. They express Arab power, pride and joy.”

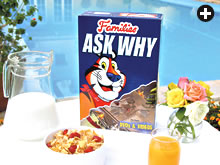

While far more politically engaged, Laila Shawa’s work exudes Middle Eastern cool. The invitation to her “Arabopop” exhibition looked like a miniature box of cornflakes—a play on branding and consumerism again. More provocatively, her “Fashionista/Terrorista” series creates discomfort by blending style with an implied threat based on stereotypes. “It’s a comment on how Palestinians are perceived,” she says. “We are judged on appearance.”

While far more politically engaged, Laila Shawa’s work exudes Middle Eastern cool. The invitation to her “Arabopop” exhibition looked like a miniature box of cornflakes—a play on branding and consumerism again. More provocatively, her “Fashionista/Terrorista” series creates discomfort by blending style with an implied threat based on stereotypes. “It’s a comment on how Palestinians are perceived,” she says. “We are judged on appearance.”

Shawa is one of the leading contemporary Arab artists living in the diaspora, outside the Middle East. In Reflections on Exile, the Palestinian writer Edward Said asks, “If true exile is a condition of terminal loss, why has it been transformed so easily into a potent, even enriching, motif of modern culture?” The answer lies in art’s pursuit of transformation. Most Middle Eastern diaspora artists live in the West, and their practices benefit from both their home cultures and their western ones, creating opportunities for endlessly hybridized styles. The artist whose painted photographs evoke Cairo’s cinematic past, Youssef Nabil, later embarked on a series of self-portraits: “I left my life in Cairo behind, and I found myself in a totally new place. I started asking myself questions about life, my life, my country and the idea of being away. In a way, I had closed a door behind me and I was no longer the person I used to be.” Whether departure is voluntary or forced, exiles can use art to rebuild themselves—one of Nabil’s self-portraits depicts him sleeping among tree roots.

Arriving in Britain from Algeria in 1977, Houria Niati became one of the pioneers introducing contemporary Arab art to the West with her series “No to Torture.” She says, “In my heart, I am displaced culturally. When I return to Algeria, I feel sad, because I am not a part of it, though I feel alienated here too, which doesn’t mean I dislike it. Now I am rediscovering my mother’s Berber ancestry and my family roots. I go to my Mum’s place to paint, and I am connecting with young Algerian artists and art students.” Niati’s multimedia installation “Out of the Ashes” contains 100 engraved wooden portraits of Algerian women, showing the designs and patterns of their clothes. “They are the protectors of our culture,” she says. A series called “Curtains of Words” celebrates her own multiculturalism in photographs based on her childhood and family, overlaid with text in Arabic, French and English.

|

| Wijdan, “Love Series,” 2008. Courtesy of Jonathan Greet and October Gallery. |

|

| Parviz Tanavoli, “Standing Heech,” 2007. Courtesy of the artist and Waterhouse & Dodd. |

n addition to these common concerns, there is also gender. Far from stereotypical submissiveness, women play central roles in contemporary Middle Eastern art.

n addition to these common concerns, there is also gender. Far from stereotypical submissiveness, women play central roles in contemporary Middle Eastern art.

In her widely exhibited series “Like Every Day,” photographer Ghadirian made studio shots of women in Day-Glo veils, over the faces of which they hold common domestic objects such as a teacup, an iron or a broom. Shirin Aliabadi and Farhad Moshiri, a married couple, poke at domestic life in their series “Operation Supermarket,” in which, for example, a box of detergent called “Shoot First” stands next to dishwasher liquid called “Make Friends Later.” In Aliabadi’s solo portrait series “Miss Hybrid,” a self-consciously glamorous young Iranian woman is photographed with bleached-blond hair, blue contact lenses and surgical tape on her nose (implying plastic surgery); she insouciantly blows a mauve bubblegum bubble that matches her denim jacket.

Samira Alikhanzadeh discovered a box of old photographs, mainly of women and children, to which she applies grid patterns, veiling some of the women and using shards of mirror to conceal the eyes of others. The viewers catch reflections and are encouraged to ponder their own identities as well as their connections with the subjects. Yet another leading Iranian woman artist, working most often in film, video and photography, is Shirin Neshat, whose 1993 series “Women of Allah” pointedly addressed gender segregation.

But among some of the younger generation, it is the lighter approach, with humor, exaggeration and style, that characterizes Middle Eastern cool. In a still from Palestinian Larissa Sansour’s movie “Bethlehem Bandolero,” we see her in a red Mexican sombrero; a bandanna covers her lower face, outlaw-style—but behind her is the wall erected by Israel to fence off the West Bank.

“But we can’t always ask our artists to reflect political issues,” says Issa. “I’m fed up with sad things and ugliness. I’m looking for positive messages, good energy. My job is to filter the best art, to present beautiful art, as well as to question things.”

Reflecting a geographical region as hybrid and complex as its many cultures, contemporary Middle Eastern artists are merging heritage and modernity into something very cool indeed.

Setting the Scene

Though London, New York and a few other cities remain dominant art centers, the explosive growth of digital communication has meant that art from countries not formerly known for local creativity, except in the heritage department, is now meaningful enough to global art buyers to be super-cool and worth a bundle. Whether the art produced the demand or the demand produced the art—or both—the result is our digital-era, post-9/11 “golden age” of spectacular artistic creativity, a cultural phoenix born from the fires of half a dozen exceedingly turbulent decades, strengthened by blossoming local cultural developments and burgeoning international interests, both intellectual and cannily capitalist.

|

| Hassan Massoudy, “Ô ami, ne va pas au jardin des fleurs. Le jardin des fleurs est en toi. —Kabir XVI”, 2008. (“O friend, do not go to the garden of flowers. The garden of flowers is in you.”) |

|

| Rachid Kouraichi, “Bronze Finial.” Both images courtesy Jonathan Greet and October Gallery. |

Though the tragedy of 9/11 had the side effect of raising western interest in Middle Eastern cultures, art historians point beyond it to two other modern political events that caused profound introspection about the future directions of the Arab world, a re-evaluation in which the region’s artists and intellectuals participated. Both the establishment of Israel in 1948 and the June War of 1967 involved military defeats that were shattering psychic events for Arab countries. Writing on the theme of “Arabness,” poet and critic Buland al-Haidari describes artists after 1967 as “vying with each other in trying to blaze a new trail which would give concrete expression to the longing for Arab unity, and end by giving the Arab world an art of its own.”

As a consequence, curator Venetia Porter writes in Word Into Art, the catalogue of the landmark 2006 exhibition of contemporary Arab calligraphy, “Arab artists, many of whom had trained in the West, or had been exposed to western art traditions, began to seek inspiration from aspects of their indigenous culture. The increased use of script by some artists can certainly be seen in the light of this.”

Rose Issa points out that, for Iranian artists, the rise of Iranian cinema to world prominence over the past three decades “has encouraged a mix of documentary films and photography mixed with fiction. This has led to a new esthetic language.” After the Iran–Iraq war, she adds, “artists wanted to document their towns, their families, their histories. Photography was the easiest and cheapest way to do this. The strength of Iranian art still comes from the way it tells real-life stories—the poetry of life, modestly done, winning prizes and influencing western artists.”

Artists, however, have been only part of the picture. Collectors, galleries, museums, governments and private businesses also play essential roles. In many countries of the region, post-colonial governments established national museums, and some included contemporary collections. Prominent among them, opening in 1977—two years before the Islamic Revolution—Tehran’s Museum of Contemporary Art became “one of the region’s most important cultural institutions,” notes Saeb Eigner, author of Art of the Middle East, and “today the country can boast some of the region’s great artists.” Indeed, Tehran has a wealth of private galleries, and artists also run Internet galleries and stage performance art in abandoned buildings, fields and mosques.

Other national museums with strong contemporary collections opened in Cairo, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Istanbul. In other places, local private and international donors often play leading roles. For example, although Lebanon is a vibrant art hub, the first Lebanese pavilion at the Venice Biennale, in 2007, was entirely supported by private Lebanese and Italian patrons.

|

| Shadi Ghadirian, “Nil, Nil, 18,” 2008. Courtesy of the artist. |

In the West, London’s Victoria & Albert Museum established the Jameel Prize for contemporary art in 2008, inspired by Islamic traditions of design and craft. Both the Oxford Museum of Modern Art and Tate Modern have deployed curators to the region, “fishing for talent,” says Issa. Other significant international exhibitions have included “Signs, Traces, Calligraphy” in London in 1995; “DisORIENTation” in Berlin in 2003; “Images of the Middle East” in Copenhagen in 2006; “Arabise Me” in London in 2006; “In Focus” in London in 2007; “Di/Visions” in Berlin in 2007; “Routes i” in 2008 and “Routes ii” in 2009 in London; “Unveiled: New Art from the Middle East” in London in 2009; and, most recently, “Edge of Arabia” in London in 2009.

In the region, pioneering galleries sprang up early on in Cairo: Mashrabiya opened in 1982, followed by the Karim Francis Gallery and the influential Townhouse. In 2000 the Nitaq Festival introduced a new generation of artists and media, including photography and video, followed in 2004 by the Contemporary Image Collective of Cairo and the Alexandria Contemporary Art Forum. Last year, Articulate Baboon Gallery was founded as “a harbourage for counter-culture in Egypt and the Middle East.”

|

| Shirin Neshat, “Games of Desire: Couple 1, 2009.” Courtesy of Gladstone Gallery. |

It is Dubai, however, that has become the new hotbed. Down below the high-rises and construction cranes are some of the region’s most cutting-edge contemporary art galleries: Majlis, B21, Cuadro, XVA, MEEM, The Courtyard, The Flying House and The Third Line (which recently opened a satellite in Doha). Within Jordan’s National Gallery of Fine Arts is the first contemporary art gallery in the Middle East, kick-started in 1980 by Princess Wijdan’s collection of her own and other artists’ work. And in 1989 the first exhibition “Contemporary Art From The Islamic World” took place in London’s Barbican, organized by Jordan’s National Gallery.

In Kuwait, the Dar Al Funoon Gallery was founded in 1994, after the Gulf War. Then, says its owner, Lucy Topalian, “it took us 10 very difficult years to even awaken an interest and awareness for art in the Middle East.” The last few years, she adds, “have gone well, thanks to the interest of the international auction houses, also the media, especially Canvas magazine, the art fairs and certain museum shows.”

Topalian mentions the Dubai-based, bimonthly Canvas magazine, founded in 2004, which—along with the quarterlies Bidoun (2005) and Contemporary Practices—have spread the word of Middle Eastern contemporary art.

|

| Rula Halawani, “Intimacy,” 2004. This series of black-and-white photographs depicts interactions among Palestinians and Israelis at an Israeli checkpoint in the West Bank. Courtesy of the artist and Selma Feriani Gallery. |

Sotheby’s was the first auction house on the scene with an auction in London in 2001; Christie’s opened a Dubai office in 2005 and held its first auction there in 2008. Sotheby’s promptly followed and added a branch in Qatar; then came Bonhams and Phillips de Pury. Continuing auctions both locally and in London have exceeded sales expectations, and in 2008 Iranian sculptor Parviz Tanavoli set a record for Middle Eastern art prices when “The Wall (Oh, Persepolis)” sold in Dubai for $2.84 million. Michael Jeha, managing director of Christie’s Middle East, says that, in 2009, “75 percent of the Dubai art sale” went to buyers “from the region, up from an average of 50 percent in previous years.”

In 2008 Christie’s introduced contemporary Turkish art. In 2009 it added Saudi artists, who that same year exhibited at both the “Edge of Arabia” show at the Brunei Gallery in London and, for the first time, at the Venice Biennale. They plan more shows in Berlin and Istanbul.

The region has its own biennale in the emirate of Sharjah, where the event is an almost venerable 24 years old. Before the sixth biennale in 2003, it focused on the more traditional genres of painting, sculpture and graphic arts; since then, its efforts have been concentrated on more contemporary art practices, such as installation, video, photography, performance, digital and Web art, emphasizing the “discourse between aesthetics and politics.”

The newest art fairs, born as annuals, are Art Dubai (2007) and Abu Dhabi (2008), which together have contributed greatly to the authority of contemporary Middle Eastern art. John Martin, co-founder of Art Dubai and a London gallery director, explains, “In the first year, our priority was to establish the credibility of the event, particularly in terms of quality and intellectual content, with 40 galleries taking part.” Since then the fair has expanded with many more galleries and events, attracting over 5000 visitors who might not otherwise have been drawn to the region. The 2011 event attracted 82 participating galleries from 34 countries.

|

| Farhad Moshiri and Shirin Aliabadi, “Families Ask Why,” from the “Operation Supermarket” series, 2006. Courtesy of the artist and The Third Line. |

Yet the golden age is in some ways only gold plate. As Saeb Eigner points out, in addition to a dearth of art-education opportunities in the region, there is “a lack of sufficient expertise, courses and research about modern art of the Arab world and Iran, reflecting the absence of this subject from the curricula of art history departments in many of the leading universities around the world.”

“We need more art history, more museums dedicated to modern art and more galleries,” says Issa. Houria Niati says that in Algeria, “in the past 20 years, art schools and galleries have opened, but media coverage of exhibitions is spasmodic, reflecting our political instability.” There is now, she adds, “a new generation of artists,” and Algeria, like the rest of the region, “is ‘kicking’ in terms of art!”

|

Writer, photographer and editor Juliet Highet is a specialist in the heritage and contemporary arts of Africa, the Middle East and India. She is the author of Frankincense: Oman’s Gift to the World (Prestel, 2006) and is working on a book series called “The Art of Travel.” She lives in England. |