|

|

| national military museum of tunisia / wikimedia commons |

| Few portraits of Khayr al-Din exist. This painting by Mahmoud ben Mahmoud was later used by engravers to produce the image on the Tunisian 20-dinar currency note. |

n his 2003 memoir Istanbul: Memories and the City, writer and Nobel laureate Orhan Pamuk recreates his extended family’s apartment building in the enclave where once lived the viziers and pashas of the Ottoman Empire. But by the 1950’s, when Pamuk was growing up, their mansions of state had become “dilapidated brick shells with gaping windows and broken staircases darkened by bracken and untended fig trees,” soon to be razed to make way for apartment buildings like his own. One of the mansions Pamuk could see from his back window was that of the 19th-century Tunisian pasha Khayr al-Din, whom the sultan had brought to Istanbul in 1878 to help save the empire.

n his 2003 memoir Istanbul: Memories and the City, writer and Nobel laureate Orhan Pamuk recreates his extended family’s apartment building in the enclave where once lived the viziers and pashas of the Ottoman Empire. But by the 1950’s, when Pamuk was growing up, their mansions of state had become “dilapidated brick shells with gaping windows and broken staircases darkened by bracken and untended fig trees,” soon to be razed to make way for apartment buildings like his own. One of the mansions Pamuk could see from his back window was that of the 19th-century Tunisian pasha Khayr al-Din, whom the sultan had brought to Istanbul in 1878 to help save the empire.

Known to history as the Tunisian Khayr al-Din (or, in Turkish, Tunuslu Hayrettin Pasha), he was born in the western Caucasus around 1822. Then as now, this Circassian region was embroiled in conflict between the local populations and Russia. His father, a local chief, is believed to have died in battle against the Russians. “I definitely know that I am Circassian,” Khayr al-Din recalled, but “I do not remember anything about my native place or my parents. Either because of war or forced migration, I must have been separated from my family very early and forever lost track of them. My repeated attempts to find them came to naught,” he wrote in a memoir.

|

| library of congress |

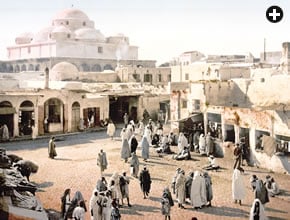

| This view of downtown Tunis, capital of Tunisia, was made in 1899, some 20 years after Khayr al-Din ended his seven-year service as prime minister and 32 years after he wrote his historic book on the principles of good government. |

He was brought to Istanbul as a child—too young to later recall by whom, or even exactly when—and, as a mamluk, was indentured to the Ottoman military governor of Anatolia. Mamluk literally means “slave” in Arabic, but “ward” would be a better description of his situation: He was raised and educated with the governor’s son in a mansion on the Asian shore of the Bosporus. But after that boy’s untimely death, Khayr al-Din found himself, at age 17, on a boat bound for Tunisia, then an autonomous Ottoman province. One of the rituals that bound the bey, or governor, of Tunis to the Ottoman sultan was the provision of mamluks for the bey’s military and civil service.

At the bey’s palace, Khayr al-Din received further education appropriate for a future member of the ruling class. He learned the Qur’an by heart, perfected the Arabic he had first learned in Istanbul, and studied French and Italian. Around 1840, he entered the army, where he studied warfare under French officers in the bey’s service. With his strong intellect, athletic build and military bearing, he advanced rapidly. By 1853, near his 30th birthday, he was a brigadier general.

|

|

|

| library of congress (3) |

| These three views of Tunis, all made in 1899, were published as “photochrom” prints by the Detroit Publishing Company, at the time the largest us publisher of popular, collectable postcards of subjects around the world. Top: “Sugar Square”; middle: “The French Gate” and above, “Outside a Moorish Café.” |

That same year, the bey sent him to Paris to represent Tunisia in a case against a corrupt Tunisian tax official who had absconded to France, obtained French nationality and sued to extort more money from the Tunisian state. Khayr al-Din denounced the defendant and countersued. The case attracted so much publicity that Emperor Louis Napoleon appointed an arbitration panel at the French foreign ministry, and as a result of Khayr al-Din’s efforts, the panel’s ruling was favorable to Tunisia.

That was the beginning of four eye-opening years in Paris, during which the young general perfected his French and carefully observed the French Republic’s customs, society and government. He was impressed particularly by the clarity of the rules governing citizens’ rights vis-à-vis each other and vis-à-vis the state.

In 1857, Khayr al-Din returned to Tunis, where he was appointed Minister of the Navy, a post he administered capably for five years. When the office of bey changed hands in 1859, Khayr al-Din was selected for the customary and prestigious diplomatic mission to Istanbul, where he presented the sultan and the pashas of the court with a cargo of gifts, and petitioned the sultan for the customary document for the bey’s investiture. In 1860, he chaired the commission that produced Tunisia’s —and the Arab world’s—first constitution that separated executive, legislative and judicial powers, along the lines of reforms in Europe and Istanbul. Later the bey tapped him to head the 60-member Grand Council the constitution created.

At the time, the most powerful and corrupt political figure in Tunisia was the bey’s prime minister—and Khayr al-Din’s superior—a mamluk of Greek origin born Georgios Kalkias Stravelakis and named Mustafa Khaznadar. He contracted for huge loans in Europe at extortionate rates of interest—paid in part to himself—and treated the state treasury as his private slush fund, even paying for the education of his two nephews in Paris out of state coffers.

Khayr al-Din found Khaznadar’s behavior repellant, but that didn’t stop him from marrying Khaznadar’s daughter Djenina in 1862. A few months later, however, he lost patience not only with Khaznadar, but with other officials, including the bey himself:

I realized that, under the guise of allowing reform measures to emanate from the Council, the Bey and Prime Minister were trying to legalize their own infractions. I tried ... to solicit their sincere interest in the country’s welfare. However, my efforts yielded no results. I did not wish, by participating in the affairs of state, to share in the deceit being practiced upon my country.

I realized that, under the guise of allowing reform measures to emanate from the Council, the Bey and Prime Minister were trying to legalize their own infractions. I tried ... to solicit their sincere interest in the country’s welfare. However, my efforts yielded no results. I did not wish, by participating in the affairs of state, to share in the deceit being practiced upon my country.

For the next seven years, Khayr al-Din refused all government posts. He and Djenina lived quietly near Tunis, raising a family. Besides gardening, reading was his passion. He ordered such French publications as Le Petit Marseillaisand Le Semaphore, and for commentary on Tunisia he read Le Journal des Débats. He also read Al Akbar from Algiers and Al Djawa’ib from Syria.

Nonetheless, he made a point of keeping on good terms with the bey and his father-in-law. He paid courtesy calls on the bey twice a month, and he headed cultural and diplomatic delegations to nine European countries. These trips “allowed me to study the foundations and conditions of European civilization and of the institutions of the great powers of Europe. And, profiting from the leisure which my retirement offered me, I wrote my political and administrative work,” he wrote.

|

| yadid levy / alamy |

| Famous for its blend of Ottoman and European neoclassical styles, the Dolmabahçe Palace in Istanbul was both home and office for Sultan Abdul Hamid ii. |

This acclaimed work, The Surest Path to Knowledge Concerning the Condition of Countries, he finished in 1867. In it, he analyzed Europe from the Middle Ages to his own day. He concluded that Europe’s development had nothing to do with climate, soil fertility, the supposed superiority of one race over another or the dominance of Christianity. (If that were so, he argued, the Papal States would be the most advanced, which certainly wasn’t the case.) Europe’s power, prosperity and progress, he felt, stemmed from stable political institutions and, in particular, was based on the rule of law.

Khayr al-Din was no slavish admirer of the West, but he believed that Muslim societies would have to adapt to an emerging world or be overwhelmed by European expansion and encroachment. So he mined western thought for ideas consistent with Islam and the cultures of the Arab world. He saw in European consultative government something comparable to the Islamic shura, or “consultation,” and he believed that good governance was a form of maslaha—the choosing of an interpretation that produces the greatest good for the greatest number.

|

| ayhan altun / alamy |

| When Khayr al-Din died in 1890, his funeral was observed here in the Eyüp Sultan mosque complex, the oldest in Istanbul and the most honored place of final rest for leaders of the Ottoman Empire. |

He also gave a straightforward argument in favor of Muslim states adopting European advances in mathematics and science. “There is no reason to reject or ignore something simply because it comes from others, especially if it had been ours before and taken from us,” he wrote in The Surest Path, referring to the knowledge from Greece and elsewhere that Muslim scholars had translated and advanced during Europe’s Dark Ages.

Rather, there is an obligation to restore it and put it to use.... The truth must be determined by a probing examination of the thing concerned. If it is true, it should be accepted and adopted whether its originator be from among the faithful or not.

And, he added, “It is not according to the person that truth is known. Rather, it is by truth that the person is known. Wisdom is the goal of the believer. One is to take it wherever one finds it.”

|

| the art archive / alamy |

| A nearly worthless currency and some 400,000 war refugees were among the challenges Khayr al-Din faced in 1878, when Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid ii, above, appointed him grand vizier—a post comparable to that of prime minister. |

Arabic and French versions of The Surest Path appeared in 1868, followed by English and Turkish translations. The book was eagerly read by the governing class in Istanbul and across the Muslim world. In Paris, the Persian ambassador had it translated into Farsi and shipped to Tehran.

In Tunisia, by 1870, Khaznadar’s corrupt ways had led to financial ruin—as Khayr al-Din had predicted. European creditors forced the bey to sack Khaznadar, and Khayr al-Din was offered the post of prime minister.

He accepted: Finally, he had a chance to put into action reforms he had thought long about. He commissioned a study that found that in his country of one million people, only 14,000 children were in primary school: He made education a government priority. In Tunis, he established Sadiki College, the first secular secondary school. He boosted the agrarian economy through tax holidays for new plantings of date palms and olive trees. He had a locked box placed in Tunis’s central square to which only he held the key and into which he encouraged people to drop comments and complaints, signed or not. Never had a Tunisian head of government tried to govern with such transparency, honesty and accountability.

Khaznadar, however, was not finished. Drawing on a fortune he had stashed in Europe, he financed a campaign to vilify Khayr al-Din in the French and Italian press, going so far as to drive down the value of Tunisian bonds on the Paris bourse just to discredit him. And the unhappy truth was that Khayr al-Din had no natural constituency to fight back on his behalf: He had contracted for no foreign loans, created no clique of yes-men, and offered no morsels of patronage to flatterers, relatives or cronies.

“The Bey appeared to be satisfied with my administration,” he wrote, “but in secret longed for the old times…. Also, supporters of my predecessor Mustafa Khaznadar, who stood to gain from his return to power, left no stone unturned to revive his fortunes.”

Khayr al-Din was forced from office on July 21, 1877. Khaznadar was back in power the next day, though he was himself quickly replaced. This reversal of Khayr al-Din’s reforms sparked a new political crisis for Tunisia, one that ended three years later in the complete loss of the country’s sovereignty when the French army marched in and established the protectorate that endured for the next 75 years.

In Istanbul, these events had not passed unnoticed. Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid ii had heard about The Surest Path (though whether he read it is unknown), and he wanted to meet its author. A year after leaving office, Khayr al-Din found himself on a steamship bound for Istanbul, where he was received warmly by the sultan and, to his own astonishment, offered the post of grand vizier. It was an offer he could hardly refuse—a redemptive, even vindicating culmination to his career. In a letter to a friend, Khayr al-Din wrote: “I would like to show the Bey of Tunis, who thinks that anyone quitting his dominions would die of starvation, that one such person has become Grand Vizier.”

|

| Rais67 / Wikimedia Commons |

| Khayr al-Din’s residence in Tunis is now the city museum. |

In his new job, Khayr al-Din faced daunting problems. Turkey had just fought a punishing war with Russia in the Balkans and the Caucasus, and enemy forces still occupied parts of the country. Nearly 400,000 refugees had crowded into the capital. Tons of nearly worthless paper money had been issued, clogging the financial system. And Egypt’s Khedive Ismail—nominally subject to the Ottoman Sultan—had repudiated foreign loans and kicked out European advisors, precipitating an international crisis.

Khayr al-Din worked long hours, even on Fridays, and at night often invited ministers to continue working in his mansion—the same one Orhan Pamuk would look out toward as a young man some seven decades later.

Within the year, most of the refugees were resettled. Khayr al-Din defused the Egyptian crisis by persuading the sultan to depose Khedive Ismail, an action that also put the bey of Tunis on notice. As for the paper-money crisis, his solution was dramatic and effective: “Although no one considered it possible,” wrote Ali Ekrem Bolayir in a memoir published in 1991, “Khayr al-Din Pasha had cages of iron installed in Bayazit Square in which huge bundles of the paper money, which were worth less in value than wrapping paper, were burned in front of the eyes of the public, and he thus rid the nation of this pestilence.”

|

| tab59 / flickr.com |

| Above: Sadiki College was founded by Khayr al-Din in 1875, while he was Tunisian prime minister. Below: In 1975, a stamp commemorated the college's centennial. |

|

| Wikimedia Commons |

But success so often invites enmity, and opposition to the incorruptible grand vizier began to build. With time, fabricated stories began reaching the ears of an increasingly paranoid sultan, who in July 1879 asked for Khayr al-Din’s resignation.

Yet Khayr al-Din remained in Istanbul until his death on January 29, 1890. His funeral services were observed with royal pomp at the Eyüp Sultan mosque, on the west bank of the Golden Horn.

Today, Tunisians regard Khayr al-Din as the inspiration for their country’s blend of tradition, modernity and openness to the world. Almost every city or town has a street or public square named for him—usually spelled “Kheireddine” in the French manner—and his palace in the old city of Tunis has been brilliantly restored as an art and culture venue. His academic creation, Sadiki College, is still a leading institution (and appeared on a Tunisian commemorative stamp). In 1968, to mark the centennial of his great book, his remains were moved from Istanbul and reinterred in Tunis.

|

| Wikimedia Commons |

| Tunisia’s 20-dinar banknote uses a design based on Mahmoud ben Mahmoud’s painting of Khayr al-Din. |

As the author of The Surest Path, Khayr al-Din is often compared with another celebrated Tunisian statesman and scholar, Ibn Khaldun, whose Muqaddimah (Introduction to History) was a beacon of knowledge in the Middle Ages.

Historian L. Carl Brown of Princeton University says that Khayr al-Din “probably felt that the problems of government and administration were similar throughout the world.” And that, he adds, “is why the book appears so modern today, in spite of a terminology and mode of argument which belong to an earlier age. In any case, this predisposition seems to have enabled Khayr al-Din to learn from Europe unburdened by inferiority complex or mental anguish. ”

To that should be added a comment by Julia Clancy-Smith of the University of Arizona, a specialist in 19th-century Mediterranean history: “Khayr al-Din’s thinking and life story—which cannot be separated from each other—hold critical importance for the 21st century. His openness to ‘foreign’ ideas, tolerance, courage in voicing criticism of Muslim religious and political elites, including the Ottoman sultan and Tunisian bey, and his cosmopolitanism—he moved with ease between Paris and Istanbul—breaks down the pernicious myth that cultural and religious identities are necessarily a source of conflict in the world.”

|

Gerald Zarr (zarrcj@comcast.net) is a writer, lecturer and development consultant. As a us Foreign Service officer, he lived and worked for more than 20 years in Pakistan, Tunisia, Ghana, Egypt, Haiti and Bulgaria. He is the author of Culture Smart! Tunisia: A Quick Guide to Customs and Etiquette (2009, Kuperard). |