For a week in January, 10 young photojournalists took part in “Portraits of Commitment,” a workshop held during the sixth biennial Chobi Mela Festival of Asian Photography in Dhaka, Bangladesh. All were students or recent graduates of the Pathshala South Asian Media Academy in Dhaka. Their assignment: A portrait-and-caption profile of someone who is contributing to the common dream of a better community, country or world.

Of course, it was not as easy as it might seem. We met not only in Pathshala’s classrooms, but also at exhibits and events, and there was a daily buzz of mobile phone calls, texts and e-mails. Some students returned to their subjects twice or more in pursuit of the elusive qualities that distinguish portraits from snapshots. Being visual storytellers, most of the photographers supported their portrait with narrative images in addition to words.

The results varied as much as the students and the subjects. But one message came through clearly: All our dreams have a story.

—Dick Doughty, managing editor

|

| Shahida Kanam |

| “If we come forward one by one, our country shall certainly be developed one day.” |

by K. M. Asad

Shahida Kanam, 20, lives in the small village of Purbodhola in northern Bangladesh. She counts herself lucky to have gone to school, and luckier still to have taken a computer class in ninth grade. The following year, Arban, a non-profit development organization based in the region, sponsored a more advanced class. She stayed in touch with Arban, and last year she became one of 12 “info-ladies.” Each travels by bicycle from village to village, carrying wireless-enabled laptop computers that allow residents of these rural communities to talk with relatives working overseas using Internet-based voice communications, such as Skype, and webcam chats. In these villages, residents often migrate to work abroad, and the webcam, Shahida says, is a particular delight to those who remain at home and see their loved ones perhaps only once a year. It has also reduced crime: False passports, visas and promises issued by unscrupulous recruiters can now be detected more easily through Internet research and direct communication with relatives overseas. “I’ll continue rendering my service to all as long as I can so that no one can be exploited for lack of education,” she says.

|

| Sayeeda Khanam |

| “I have tried to document time, space, society and history. It has not been so silky-smooth.” |

by TASLIMA AKHTER

In the 1950’s, it was rare to see a woman carrying a camera in East Pakistan (as Bangladesh was then called). But Sayeeda Khanam had been photographing since 1940, when at age 13 she received from her sister the gift of a Rolleicord twin-lens reflex camera—which she still owns. “The different colors of the skies, the beauty of the Padma River, different birds” inspired her, she says, but later she turned to journalism. In 1956 she participated in an international exhibition in Dhaka, becoming the country’s first female professional photographer. In 1971, during Bangladesh’s War of Liberation, she took a photo of two rows of young women dressed in white saris with rifles on their shoulders. The image became one of the most famous photographs of the war. For many years she worked for Begum women’s magazine and various other press outlets. Now 73, she also recalls the celebrities she photographed—among them Queen Elizabeth ii of Britain, the empress of Japan and Neil Armstrong, the first man to walk on the moon.

|

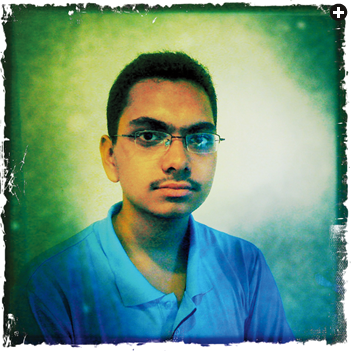

| Mushfiqur Rahman |

| “The smallest change has the power to trigger substantial, lasting improvements. One should not hesitate to be the first one to take such a step.” |

|

| Faruk Hossain |

by ASHRAFUL AWAL MISHUK

In August 2006, 12 high school students in Dhaka founded the One Degree Initiative (1°) to get youth in Bangladesh engaged in community service. Now, 1° has more than 1500 members, and international branches in Nepal and Canada. In Bangladesh, it has run some 50 projects, each designed to be a life-changing experience for both volunteers and recipients. Mushfiqur Rahman, 20, sits on the group’s executive committee while also studying business at the American International University of Bangladesh. In December, Rahman helped organize a medical camp at Alok Shishu Shikkhaloy, a primary school in Dhaka’s Agargaon slum. More than 100 families received free medical services from doctors organized by 1°, and students of the school themselves acted as volunteers: One of the student leaders from the school was 13-year-old Faruk Hossain, who has continued to act as a liaison between his classmates and 1°.

|

| Shudhir Chandra Bardhain |

| “An educated nation will not remain a poor one.” |

by A. M. Ahad

Born in 1940, an accountant by profession, Shudhir Chandra Bardhain resigned his government job in 1969 and sold family property to found the Bhulakut K. B. Higher School. It opened its doors in 1972, a year after Bangladesh’s independence, and it offered the new nation’s first free education for rural girls. Bardhain remembers going door to door, family to family, in his village of Bhulakut, some 170 kilometers (105 mi) east of Dhaka, persuading villagers that education could improve their lives and that “an educated mother makes an educated nation.” The school also enrolled boys, but charged tuition for them; it was free for girls in order to encourage families to send their daughters as well as their sons.Today, the school is still open, and every morning starts with a chorus of alphabets and numbers for some 550 girls and 330 boys.In 2008, Bardhain was one of 10 recipients of the Shada Moner Manush (“people of generous heart”) Award sponsored by Unilever Bangladesh.

|

| Munir Hasan |

| “I have always dreamed of turning my country into a nation of world-class, advanced mathematicians and scientists.” |

by Hasan Raza

Since 2005, Munir Hasan has led Bangladesh’s students in the International Mathematics Olympiad, but—perhaps more important—he is the leading creative force revitalizing the nation’s approach to math education. Using a network of community-building math festivals, daily newspaper columns, teacher training and new textbooks that emphasize exploration and questioning rather than rote memorization, he is “making math a joyful priority,” according to the Ashoka Foundation, which elected him a fellow in 2008.

|

| Shykh Seraj |

| “Farmers are the real architects of Bangladesh.” |

by M. R. K. Palash

Recipient of 28 national and international awards, Shykh Seraj is the pioneer of agricultural journalism in Bangladesh. In this mostly rural nation, that makes him a star. He has produced more than 1000 episodes of five different television programs, starting with “Mati o Manush” (“Soil and Men”) back in 1982, the year he graduated from Dhaka University with a master’s degree in geography. He has covered every imaginable facet of agriculture, from rice-farming techniques, shrimp and fish farming, fertilizer choices, beekeeping and dragon-fruit production to urban and schoolyard gardening, soil health, land-use disputes, conflicts between small and large growers, technology impacts and rising sea levels. His use of television to reach often illiterate or semi-literate farming families is widely credited with hunger relief and improved prosperity nationwide. Most recently he has launched a series of Web sites and podcasts under the banner of “e-agriculture.”

|

| Tenjing Chakma |

| “For my native people, I’ve felt something instinctive inside myself.” |

by N. Haider Chowhury

Born into the Chakma, the most prosperous of 13 major tribal communities in the Chittagong Hill Tracts of southeastern Bangladesh, 31-year-old Tenjing identifies himself among a new breed of fashion designers. In the 1990’s, he studied design in New Delhi and Calcutta. In 2000, he returned to Bangladesh, but the emerging fashion houses of Dhaka did not interest him, and the rapid assimilation of international styles—and the abandonment of traditional ones—among his own Chakma people drew him back to the Hill Tracts. Now, working in the small city of Rangamati with four employees and contracts with a handful of Chakma weaving families, he produces fusion designs that bring together traditional and contemporary. Most popular are his wedding dresses, which show now in Dhaka, in Chittagong in eastern India and elsewhere.

|

| Iffat Ara Sarker Eva |

| “I will work for people until I am physically unable to do the job.” |

BY D. M. SHIBLY

Yasmin was still in her teens when Iffat Ara Sarker Eva met her at Safe Home, a halfway house in Dhaka for destitute youth separated from their families. Yasmin said she didn’t know where her family was. She recalled being sent at age 13 to live with her grandmother, a beggar in the town of Dinajpur. That was after her parents’ divorce, she said. Police had brought her—rescued her, says Eva—to Safe Home, where Eva has worked as a coordinator since 2008. There, her job is to reunite troubled, runaway and abandoned youth with their families—if the families can be found. Finding Yasmin’s family, Eva says, was particularly difficult. Yasmin recalled little, partly out of shame; since she had run away, her grandparents would not take her back. Eva learned that Yasmin’s father was a rickshaw driver in a slum in Dinajpur. She finally found him, sitting on a footpath on a bridge. They shared tea. He agreed to take her back. Four months later, the father arranged a marriage, with Yasmin’s consent. Yasmin asked Eva to attend the wedding, and to remain her legal guardian. Now the couple has a son, and Eva, age 52, has since then accumulated more than 20 such success stories.

|

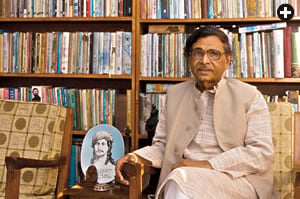

| Abdullah Abu Sayeed |

| “People do not become enlightened. That is the name of a dream. They try and become enlightened. That attempt is the enlightenment…. To me, what is important is the start.” |

|

| Finalists in the nationwide annual student reading contest sponsored by Kendro celebrate in Dhaka in January. |

BY SYED ASHRAFUL ALOM

Writer, television presenter, cultural activist and professor of Bengali language at Dhaka College, Abdullah Abu Sayeed is perhaps best known as the founder in 1975 of Dhaka’s World Literature Center (Bishwa Sahitya Kendra), known popularly as “Kendro.” Now counting more than 125,000 members and housing one of the nation’s best libraries, Kendro also offers classes on world literature at more than 500 schools—and provides the books to the students. In 2004, Abu Sayeed’s commitment was recognized with the Ramon Magsaysay Award, often called “the Asian Nobel,” for his contributions to “cultivating in the youth of Bang-ladesh a love for literature and its humanizing values through exposure to great books of Bangladesh and the world.”

|

| Kaniz Almas Khan |

| “I want every woman to be a companion in my success.” |

BY M. N. I. CHOWDHURY

Beginning with her first tiny salon, called Persona, in 1990, Kaniz Almas Khan has now become the owner of Persona Group, a chain of women’s beauty salons and spas, as well as the lifestyle magazine Canvas. In 2009, she was named most outstanding businesswoman in Bangladesh. What sets her apart from other entrepreneurs are her employees, who now number more than 1400: 99 percent of them are women, and many come from underprivileged, even dire, backgrounds. They include members of rural minority tribes and nearly two dozen survivors of acid attacks. All have been trained by Khan and her associates. “The women of our country have a lot of potential,” she says. “If they want, they can step in along with men and build a better future.”

|

"Portraits of Commitment" was led by Dick Doughty, managing editor of Saudi Aramco World, and D. M. Shibly, an instructor at Pathshala South Asian Media Academy and a staff photographer at ICE Today magazine. Bottom row, from left: Students M. N. I. Chowdhury and M. R. K. Palash, Pathshala Vice Principal Abir Abdullah, Dick Doughty and D. M. Shibly. Top row: Students K. M. Asad, Ashraful Awal Mishuk, Syed Ashraful Alom, Taslima Akhter and Hasan Raza. Not shown: Students N. Haider Chowhury and A. M. Ahad. Special thanks to Pathshala Principal Shahidul Alam, workshop coordinator Snigdha Zaman and tutor Munem Wasif for the support and encouragement that made this article possible. |