orocco and England today are linked most conspicuously by tourism, but in the 16th

and 17th centuries the two countries were more closely connected, both politically

and economically. From this period, the surviving correspondence with North Africa

—predominantly Morocco—in the uk State

Papers amounts to more than 20,000 folios in various languages, and there were nearly

a hundred embassies exchanged among European and North African rulers.

orocco and England today are linked most conspicuously by tourism, but in the 16th

and 17th centuries the two countries were more closely connected, both politically

and economically. From this period, the surviving correspondence with North Africa

—predominantly Morocco—in the uk State

Papers amounts to more than 20,000 folios in various languages, and there were nearly

a hundred embassies exchanged among European and North African rulers.

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

scala / white images / art resource |

|

university of birmingham |

|

| |

In 1588, George Gower painted the "Armada Portrait" of Queen Elizabeth i,

portraying her with her right hand resting on a globe set conspicuously beneath

her crown. This was a symbolic assertion of her power following the English defeat

of the Spanish Armada, which Gower depicted in the painting's two background windows.

Seven years earlier, Elizabeth had authorized a large shipment of timber to aid

Morocco in building ships to attack Spain. |

|

During

'Abd al-Wahid ibn Masoud's term in London, he negotiated commercial and military

trade agreements as well as continued alliance against Spain. Some suggest that

the portrait may have inspired Shakespeare's protagonist in "Othello," published

a few years after 'Abd al-Wahid's embassy. |

|

The Anglo-Moroccan connection originates in the quarrels between the two half-sisters

Queen Elizabeth i and Queen Mary i.

Elizabeth suspected that Mary's husband, Philip ii of

Spain, had designs on England, and she was consequently interested in an ally who could

join in attacking Spain. On the Moroccan side, there was considerable enthusiasm for

expelling the Spanish and Portuguese from the several Moroccan coastal cities they had

conquered. The Moroccans also wanted naval support in case of further encroachment by

the Ottoman Turks, who were eager to extend their empire west from Algiers into Morocco.

It was for this last reason that the Moroccan sultan Ahmad al-Mansur was unwilling to

collaborate with the Ottomans despite Ottoman consideration of an invasion of Spain:

He preferred instead an alliance with the English.

|

|

scala / white images / art resource |

|

King Philip ii of Spain with his wife, Queen Mary

i of England, in 1558. The Anglo-Moroccan connection

had its origins in the quarrels between Queen Elizabeth i

and Queen Mary, who was Elizabeth's predecessor on the throne. Elizabeth feared that,

after Mary's death, Philip would advance a claim to succeed her.

|

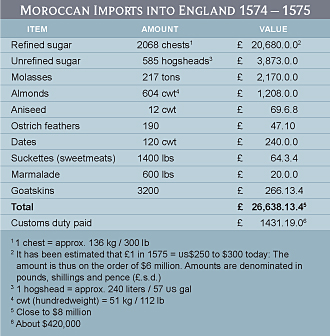

There were also excellent opportunities for trade (See "Moroccan Imports into England," below).

As well as commercial exchanges, such as Moroccan sugar and dates for English cloth—

or for a bass lute for the sultan—both nations were also interested in war materiel.

England wanted Morocco's excellent saltpeter with which to manufacture gunpowder, while

Morocco sought cannonballs and guns, as well as shipwrights and timber for shipbuilding.

These were sensitive matters: European powers at times accused England of trading arms

to an enemy, and the same reproach was raised by Muslim powers against Morocco.

The third issue was piracy. Here, both Moroccan and English sovereigns' attitudes

varied with the political situation. Elizabeth, for example, tacitly encouraged

Francis Drake's piracy against the Spanish, while at the same time wanting Morocco

to rein in the notorious Rovers of Salé and permit ransom for English subjects taken

as slaves. The sultan, on the other hand, though anxious to bring Salé under his

control, was, like Elizabeth, not loath to profit from the pirates' activities. In

short, there was much to negotiate.

The first recorded English merchant vessel to reach Morocco docked in 1551. In the following

year, three ships set sail from Bristol and arrived at Safi and Agadir to unload, among other

things, cloth, coral, amber and jet (gem-quality lignite). Twenty years later, in 1576, English

merchant-envoys were at the court of Sultan Moulay 'Abd al-Malik, where they negotiated the

exchange of saltpeter for a large quantity of cannonballs. On July 10 of that year, 'Abd

al-Malik wrote to Elizabeth, saying that he was sending her an ambassador. She replied that,

in view of the subjects of their negotiations, the ambassador's visit should be kept a secret.

If the visit indeed occurred, then her suggestion was well heeded, for there are no other

records of it.

|

|

|

'Abd al-Malik's successor, Ahmad al-Mansur, was equally interested in trade with England.

In 1581, after Philip ii was crowned king of Portugal,

Elizabeth gave permission for 600 tons of first-class wood, probably oak, to be felled in

Sussex and Hampshire for export to Morocco so that al-Mansur's fleet might attack Spain.

In 1588, after the English defeat of the Spanish Armada, al-Mansur sent an envoy, Marzuq

Ra'is, to the court of Elizabeth to discuss a joint attack against Spain. Al-Mansur's letter

fairly pleads for secrecy:

When he alights in your company and makes his camel kneel, if God wills, in your valley,

you will direct your solicitude towards him so as to receive what he has by word of mouth

and so that he may confirm it to you verbally and face-to-face. Then, if God wills, close

your fingers upon it and fasten over it the buttons of your thoughts.

Marzuq was well received but the negotiations were inconclusive.

In 1600, al-Mansur sent his private secretary, 'Abd al-Wahid ibn Masoud, to England together

with an accompanying delegation that remained for six months. Ostensibly on a trade mission,

'Abd al-Wahid was also quietly negotiating the alliance against Spain and, on both sides,

the purchase of war materiel.

Like other foreign visitors, 'Abd al-Wahid would have generated a great deal of interest both at

court and in the street. A striking portrait of him now hangs at the Shakespeare Institute at

Stratford-on-Avon. Some scholars have suggested that the interest in North Africa that 'Abd

al-Wahid helped generate inspired Shakespeare's 1603 "Othello," although the play's plot is

based on an earlier Italian story.

The death of both Elizabeth and al-Mansur in that same year, and subsequent struggles for

succession in Morocco and, later, the Civil War in England, shifted relations between the

two countries, but the underlying common interests endured. On several occasions, James

i sent an ambassador, John Harrison, to negotiate both for

the liberation of British captives and, with the de facto ruler of Salé, for a

joint offensive against Spain. He later wrote a short biography of the Moroccan ruler titled

The Tragicall Life and Death of Muley Abdala Malek.

In 1637, Jawdhar ibn 'Abd Allah arrived in London on an embassy to Charles

i. Like the other ambassadors, he attracted enormous

attention, and indeed, a booklet was even published for those who had not had the good

fortune to witness the events: The arrivall and intertainments of the Embassador

Alkaid Jaurar ben Abdalla. The frontispiece is an engraved portrait of the ambassador,

who was from the Coimbra region of Portugal. Captured and castrated when he was eight

years old, he rose to become a trusted advisor of Moulay Muhammad, the first sultan of

the 'Alawi Dynasty that still rules Morocco today. High on his agenda were the enduring

problems of piracy and illegal trading; however, as a goodwill gesture, he was accompanied

to London by a number of English slaves freed by the sultan.

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

scala / art resource |

|

national portrait gallery |

|

| |

In 1637, the pomp and ceremony of Jawdhar ibn 'Abd Allah's embassy to King Charles

i, left, prompted publication of a booklet describing

the events. This engraving of the young ambassador, right, appeared on its cover. |

|

Unfortunately, although Jawdhar was quite young, fits of ill health—perhaps malaria—

interrupted the program planned for him. Nevertheless, he entered London with great ceremony:

He and his escort traveled by barge from Greenwich to the Tower of London, "where they were

attended by thousands and tens of thousands of spectators." Riding in the king's own coach,

he was attended by "at least 100 coaches more, and the chiefest of the citizens and Barbary

merchants bravely mounted on horseback, all richly apparelled, every man having a chain of gold

about him: with the Sheriffs and Aldermen of London in their scarlet gownes with such abundance

of torches and links, that though it were night, yet the streetes were almost as light as day."

On November 5, after a fortnight's rest to recover his health, the ambassador rode out in

another great procession to meet the king. The order is described in detail in The arrivall

and intertainments..., including the liberated slaves and a gift of highly prized Barbary

horses, one of which was said to be worth more than $250,000 in today's money. All London

turned out to cheer, and it seems that the ambassador was delighted, although later

disappointed he was not well enough to attend the lord mayor's show, which he had his

attendants describe to him in detail.

The booklet describing these events, which included a short description of Morocco, was written

not as part of official diplomatic correspondence, but rather for a British public eager for

information. It is therefore interesting to read how warmly the author speaks of the ambassador:

This Alkaid Embassador hath an innated inclination to any thing that is noble, worthy and

befitting a gentleman; he is devoute and zealous in those wayes and rules of religion wherein

he hathe beene brought up.... Hee is courteous, bountifull, charitable, valiant, and a severe

punisher of enormities, as drunkenesse, or any prophanesse in his house; he speaks the Spanish,

Italian and Arabian tongues; and in a word, for humanity, morality and generosity, hee is a

most accomplish'd gentleman.

Some years before Jawdhar ibn 'Abd Allah's mission, the English had been dissuaded from

acknowledging the legitimacy of the breakaway state at Salé, and Charles i

had refused to ratify the agreement brought by its envoys. Moulay Muhammad's long letter

to Charles on this occasion was intended largely to promote trade cooperation and, as fellow

monarchs, to join forces to suppress rebellion and piracy. It was subsequently published as a

pamphlet for the general public:

Now because the islands which you Govern, have ever been famous for the unconquered strength

of their Shipping, I have sent this my trusty servant and Ambassador, to know whether in your

Princely wisdom, you shall think fit to assist me with such Forces by Sea as shall be answerable

to those I shall provide by Land.

While for a variety of reasons none of the many proposed Anglo-Moroccan attacks on Spain ever

came to much, the joint attempt to clear out the nests of pirates "that have so long molested

the peaceful Trade" was, at this particular moment, more successful.

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

national trust photo library / art resource |

|

chiswick house / english heritage photo library

/ bridgeman art library |

|

| |

Muhammad ibn Haddu, right, on his mission to King Charles ii,

left, made the most lasting impression of all the North African sultanates' diplomats.

Impeccable courtly manners, displays of horsemanship and an appreciation of English theater

made him "the fashion of the season." |

|

Years later, another embassy made great impact on the general public, the nobility and even the

academic world: that of Muhammad ibn Haddu, always referred to in the English sources as "Ben

Haddu." This was less because of his negotiations than because he seems to have had wide interests,

and he kept very much in the public eye. As John Evelyn puts it in his diary, "He was the fashion

of the season." Ben Haddu discussed the usual issues, peace and a trade treaty, though the document

was never ratified. (This in spite of the diarist Anthony Wood's entry for February 16, 1682,

which states that "an everlasting peace was concluded between our king and the emperour of Morocco

by his embassador in London.") This was largely because the English continued to occupy Tangier,

which gave them control over the Straits of Gibraltar, and because some English merchants

continued to trade illegally and not pay the required taxes.

Ben Haddu immediately won the approbation of the crowds by his splendid horsemanship (See "From

the Diary of John Evelyn," page 21) and of his peers by his exquisite manners. He seems to have

used his six months in England to experience as much of the country as possible. He visited the

Royal Society, which had been founded officially in 1660, and on May 31, 1682 he was given the

unusual distinction of being made an honorary fellow; his signature is to be seen in their register.

He may even have met one of its founding members, Sir Christopher Wren, when he went to look at

construction work on St. Paul's Cathedral, where he made a gift to the workmen of £15 (worth about

$3000 today). His sultan, Moulay Ismail, was passionately interested in architecture and was at

the time in the process of transforming his royal city, Meknès, so Ben Haddu probably passed on

a detailed account of the occasion.

His travels outside London took him primarily to Oxford and Cambridge and from there to Newmarket,

then as now a great center of horse racing and breeding. This would surely have been of particular

interest, since North African barbs were highly prized, and there, once again, a display of

horsemanship by himself and his companions was met with great admiration.

At Cambridge, the entertainment was more sober. There had been a chair of Arabic there since 1631,

funded by a merchant, Thomas Adams. The university granted Ben Haddu an academic distinction—perhaps

an honorary degree—but the banquet offered by the vice—chancellor was less successful.

Possibly because they were unsure of his dietary prohibitions, the meal was composed of fish, including

eels and sturgeon, and after it, the ambassador had to lie down at the provost's lodgings at King's

College until he recovered enough to depart.

There is a detailed account of his visit to Oxford in the diary of Anthony Wood, who recorded that

he stayed at the Angel Inn, the best hotel in the city, preferred by nobles and even royalty.

There, he would also have had the benefit of the two oldest coffee houses in England, established a

few years earlier. One of them, the Queen's Lane Coffee House, is still in existence today. But

judging by Wood's diary, Ben Haddu would have had little time for drinking coffee. First, a reception

by the notables of the university, at which the distinguished Arabist Edward Pocock said "something

in Arabick which made him laugh," and then on the following day what must have been a most exhausting tour:

In the morning about 8 or 9, he went to Queen's College and saw the Chap-el, hall, and had a horne

of beer but did not drinke. – Thence to the Physick Garden where Dr Morison harangued him.

– Then to Magdalene College where the president spake something to him; went into the chapel,

beheld the windows and paintings; thence round the cloister. – And so to New College where

he saw the chapel while the organ played. – Thence to St John's. – Then to Wadham [Wren's

college]. – Thence to All Souls; saw their chapel. Thence to University College. – And so

home to the Angell."

Again unwell after dinner—or perhaps simply exhausted—the ambassador arrived late at the

formal reception at the Sheldonian Theatre, where there were more speeches and music. Once again,

his presence caused a sensation. Wood relates:

'Tis thought that there was in the Theater 3000 people, and a thousand without that could not

get in; never more people in it since it was built [some 20 years earlier, by Wren] –

He went thence up to the public library, where he was entertained by an Arabick speech by Dr

Thomas Hyde [official interpreter to the court] which he understood.

|

| museo correr /

bridgeman art library |

|

Dating from 1651, this section of a Venetian nautical map, oriented with west upward, shows

coastlines, harbors, ports and ruling powers. While North Africa, the Iberian Peninsula and

Europe received the cartographer's detailed and even creative attention, he drew no ruling

house at all in Great Britain.

|

|

| bridgeman art library |

|

This mezzotint of "Ben Haddu," by Edward Lutrell, was published in 1682, the year of his embassy.

|

The day continued with more sightseeing and a banquet. At the end of this very long day, "the

vice-chancellor presented to him certaine books in Arabick."

We do not know which books he was given, but it is tempting to think that they included copies

of Pocock's own editions and translations of Arabic texts, such as his 1661 translation of

al-Tughra'i's famous Lamiyyat al-'Ajam (Qasida Rhyming in L) from the 12th century—

the first major work of Arabic poetry to be introduced to a western audience.

Interest in Morocco, the Arab world and Islam was undoubtedly stimulated by these direct

contacts, and Ben Haddu was in this sense an excellent cultural ambassador. Throughout the

17th century, Oxford in particular had been building up its collection of manuscripts, as

merchants returning from North Africa and the Levant were encouraged to bring back at least

one book. Medical students were supposed to have a basic knowledge of Arabic in order to

read the medical texts, although probably few of them did.

At the popular level, the interest was even more striking: Newspaper articles, pamphlets,

poems, histories and plays abounded. Many ambassadors, from various countries, were taken

regularly to the theater as part of their official entertainment, but they often returned

for their own pleasure, sometimes asking for a particular play. Ben Haddu saw "The Ingratitude

of the Commonwealth"—a version of "Coriolanus" "with dancing." A few days later, he was

"extreamly pleased" with "The Tempest," went to "The Bloody Brother" and "to his great

satisfaction" saw "Macbeth," among other productions. It is not clear whether or not he

saw "The Empress of Morocco," a great success and one of a number of plays on Moroccan and

Middle Eastern themes written to satisfy the popular interest. Later ambassadors showed equal

interest in the theater, although in 1724 ambassador 'Abd al-Qadir Perez seems to have

preferred more romantic and less political plays.

Trade with Morocco, and the visits of the Moroccan ambassadors, undoubtedly fed interest in

the Muslim world and encouraged reappraisal of the relationship between Christian and Muslim

spheres of influence. It is harder to know, however, what influence the experiences of the

ambassadors themselves may have had back home in Morocco, because so much less has survived

in the way of contemporary records—although material is still surfacing.

In terms of political negotiation, the embassies were less successful. It was unfortunate

that Charles ii ignored Ben Haddu's private advice (See

"Letter from Ben Haddu...," above) and, instead of selling or bartering Tangier, elected to

destroy and abandon it. This failure to pay due attention to Moroccan intelligence was to be

repeated in the early 18th century, as the frustrating experiences of the ambassador Ahmad

Qardanash make clear, and such carelessness worked to England's detriment. By and large, the

ambassadors' attempts to arrange treaties met with limited success due to reservations on

both sides, but as cultural ambassadors, their roles were invaluable, and the two countries

remained on largely amicable terms for several centuries.

|

Caroline Stone (stonelunde@hotmail.com)

divides her time between Cambridge and Seville. Her latest book, Ibn Fadlan and the

Land of Darkness, translated with Paul Lunde from the medieval Arabic accounts of

the lands to the far north, was published in December by Penguin Classics. |