hat connects seed banks in Syria, Russia and New Zealand to Khuvaydo Ismatuloyev, a

29-year-old farmer ready to harvest his rye crop in eastern Tajikistan, is not a

simple story, yet it is one of vital importance. The genetic makeup of Ismatuloyev's

plants, cultivated in a short growing season and under highly stressful conditions at

more than 2000 meters (6500') altitude in the shadow of the Pamir Mountains, may

represent science's best hope to overcome some future global food crisis caused by,

say, a killer plant fungus or voracious pests or a sudden shortage of essential

chemical fertilizers.

hat connects seed banks in Syria, Russia and New Zealand to Khuvaydo Ismatuloyev, a

29-year-old farmer ready to harvest his rye crop in eastern Tajikistan, is not a

simple story, yet it is one of vital importance. The genetic makeup of Ismatuloyev's

plants, cultivated in a short growing season and under highly stressful conditions at

more than 2000 meters (6500') altitude in the shadow of the Pamir Mountains, may

represent science's best hope to overcome some future global food crisis caused by,

say, a killer plant fungus or voracious pests or a sudden shortage of essential

chemical fertilizers.

Ismatuloyev's rye crop is a "landrace," a primitive, highly local variety of this cereal

grass. His forefathers hand-selected seeds from individual rye plants for replanting,

repeating the process over many generations, because of the superior characteristics of

those individual plants. The seeds thus selected have a genetic makeup that allows them

to survive drought, frost, poor soil and bugs that are resistant to chemical pesticides.

Breeders can cross plants grown from these seeds with modern varieties of rye, or scientists

might splice their genes into other rye seeds—or even perhaps into different plants

altogether—in order to add such characteristics as frost hardiness, drought resistance

or salt tolerance in the face of changing conditions.

That is why a team of scientists from Aleppo's International Center for Agricultural

Research in the Dry Areas (icarda), St. Petersburg's Nikolai

Vavilov Research Institute of Plant Industry (vir) and

New Zealand's Margot Forde Forage

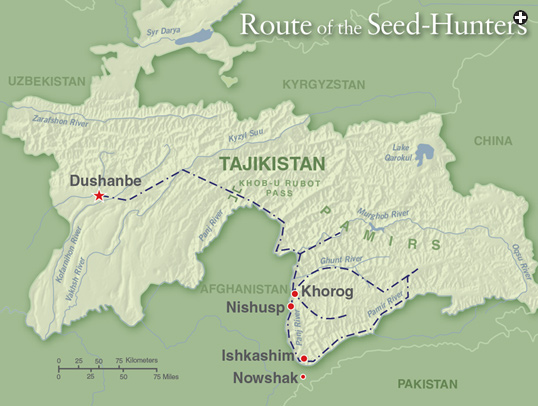

Germplasm Centre has come to collect seeds on a three-week mission that will take them to

farmers' fields and uncultivated roadsides all over the province, from the lower valleys

of the Panj River, a tributary of the 2540-kilometer (1500-mi) Amu Darya, up toward the

Bam-i-Dunya, the "roof of the world," in the High Pamirs, at mountain passes over 4000

meters (13,000') high.

Also on the mission are Saidzhafar Abdulloyev, a specialist in the Allium—onion

and garlic—genus, and Mirullo Amonulloyev, who is interested in Pamiri varieties of

wheat and barley. Both men are from the Plant Genetics Resources Center of the Tajik

Academy of Agricultural Sciences. Marco Polo, who traveled through this region some

750 years ago, called the Pamirs after their Chinese name, the "Onion Mountains"—

most likely because of the ten wild varieties of onion that grow here. Abdulloyev is

keen to find them. According to Pamir scholar Robert Middleton, Marco Polo may have

followed the same route as this team plans to, up the Ghunt River valley, which enters

the Panj at the provincial capital of Khorog.

|

An American historian of science and an Australian farmer complete the mission team.

Together, they are looking for all cultivated varieties of food and forage plants—

everything from red- and white-eared wheat (called surkhak and safedak

in local languages) to beans and peas and clover and chicory. As well, they are searching

for those plants' wild relatives, such as species of the Aegilops genus, called

goatgrasses, which are precursors of common wheat, and medusaheads, or Taeniatherum

caput-medusae. Those plants are considered noxious field weeds in developed countries,

but they have been found at Iranian archeological sites. Presumably, therefore, they were

of some value to humankind once; perhaps they could be again.

The Pamir Mountains are considered one of the world's centers of food-plant diversity,

according to followers of pioneering Russian botanist Nikolai Vavilov, who died in a

Stalinist prison in 1943. Vavilov's first seed-collecting mission in the summer of 1916

was to this region, and he was struck by its extreme isolation—Badakhshan province

makes up half of Tajikistan's area but contains just three percent of its population—

contrasted with its great diversity of food-plant varieties. He theorized that it must

have been a "center of origin" of agriculture, the source of cultivated seeds that had

then diffused outward to other areas. Since Vavilov, scientists have been fascinated by

this region as well as his other high-altitude hotspots of biodiversity: the Ethiopian

highlands, the Andes, and the Caucasus. Icarda is making

its sixth visit to Tajikistan, and Sergey Shuvalov, the Russian delegate from vir, has

come five times since 2003.

The team's first collection site is at the roadside near Kishlak village, en route to the

Pamirs, where they find mixed varieties of wheat in a single field. They collect the seeds

in sealed envelopes, recording such key data as the size of the area collected from, its

degree and direction of slope, the soil texture, salinity, acidity and parent rock, and its

drainage. Gps instruments record altitude, latitude and

longitude. The scientists aim to collect seeds from at least 100 plants per species per

site in order to capture the genetic diversity of the plant population there and to maximize

the likelihood of getting viable seeds that will germinate.

If the quantity of seeds collected is not adequate for testing, they will first be "multiplied"

in seed-bank greenhouses or grown out in consecutive harvests to generate more seeds. They

will then undergo characterization studies to determine such characteristics as how many days

the plants take from germination to flowering, the number of seed heads per plant and seeds

per head, and the amount of protein they contain.

In time, the collected seeds may undergo tests with varying light, temperature, moisture

and soil quality to determine their environmental tolerances. All this information is

then entered in specialized websites and the seeds are shared with other seed banks and

research centers as requested, and often co-stored in the newly opened Svalbard Global

Seed Vault in northern Norway, the so-called Doomsday Vault, buried deep in permafrost so

that even a worldwide electrical failure would not degrade its collection.

New Zealander Zane Webber is especially eager to find seeds of forage plants that are

infected with beneficial fungal endophytes that help them resist environmental stresses.

He will not know if he is lucky until he can put them under a microscope and test them in

a greenhouse back home, but if so, the fungus could be introduced to commercial seed lines.

Webber's understated eureka moment comes early in the trip, just before the group passes

over the 3252-meter (10,650') Khob-u Rubot Pass, the gateway to the Pamirs, when he finds

red clover growing at 2800 meters (9200')—near its maximum, and an altitude at which

such endophytes might well thrive.

Seventeen-year-old Behruz Muzafarov, of nearby Razak village, some 25 kilometers (14 mi)

from the nearest market, has five brothers, two currently working in Moscow to supplement

the income from the family farm, with its meager crops of potatoes, wheat, barley and flax.

Even though the potatoes he grows are a food plant of New World origin, introduced here

by the Russian army in 1910, the Muzafarov family's careful selection of seed potatoes

from each year's crop is slowly adapting the plants to this Old World environment. Though

the region seems as mountainous as the Andes, its different soil, rainfall, pest and disease

characteristics make it a decidedly different environment from the agricultural point of view.

Behruz also grows a forage crop called sainfoin—the French name means "healthy hay,"

but the plant is in fact a legume—that is highly nutritious, easily digestible and

early-maturing. Shuvalov notes, however, that Behruz's long-awned wheat variety is probably

not a landrace, but more likely grown from commercial seed.

Icarda taxonomist Jose Piggin's jeweler's loupe comes in

handy for identifying species of Medicago (medicks or burclovers) and Vicia

(vetches, wild relatives of the broad bean), as she counts tendrils, ligules and leaves, or

checks whether the seed cases of wheats and ryes are pubescent (hairy) or glabrous (smooth).

When she needs a reference, she turns to the relevant pages of the 11-volume Flora of

Turkey, published by Edinburgh University, which captures most of the plant life across

Central Asia. But much of what she knows, she knows on sight. Of special interest to her is

grass pea, Lathyrus sativus, related to sweet pea. Icarda

has a program to grow improved varieties of this plant, which is an insurance crop

in many countries because of its hardiness.

|

Seed collectors themselves are a bit like foraging animals, wandering far and wide in

search of the same plants, and Shuvalov, the expedition's chief logistics planner,

translator and route finder, often has to whistle them back to the vehicles. He is

aware of the honor of following Vavilov's footsteps, but doubts that he will have time

this trip to collect anything near the 200 species and varieties that his compatriot

did here 100 years ago.

It is a shame that this mission is not focused on orchard crops, for the Pamirs are

famous for their mulberries, apricots, apples and pears, sold fresh at the roadside

and put out for drying on flat rooftops. Khukmatullo Akhmadov, president of the Tajik

Academy of Agricultural Sciences, had sent the team off with a glowing discourse about

his country's 300 varieties of apricot and 180 varieties of grape, saying that the

scientists were in luck to be here during harvest season. "One day everything may

disappear," he told them. "So everything you collect is valuable, whether it is unique

to Tajikistan or not. One day the only surviving variety of an important food plant may

be found in the seed bank."

Farmers in Nishusp village in the Shugnan district cultivate rye and beans in the same

field, as is usual in the Pamirs, where arable land is scarce. They are then harvested,

threshed and milled together, and the combination used to make soups, stews, noodles

and a black bread called mahin mahourj, or "made from beans." Short-stemmed

wheat and long-stemmed rye are also sometimes grown together in the same field. Though

they have different maturing times, the stalk connecting each seed to the ear of the

early-ripening crop is so strong that it can stand in the field without loss until

the other crop is ready.

|

Farther up the Panj River Valley, and still just across the river from Afghanistan,

is the Kuh-i Lal spinel mine, whose gems were known as "balas rubies" (a corruption

of the name Badakhshan) in medieval Europe, and praised in the verse of Chaucer and

Dante. In a nearby village, farmer Khuvaydo is irrigating his rye crop one last time

before harvest. He faces a long winter, often getting three meters (10') of snow, and

can expect his first frost in October. A woman bundles a few ripe ears of rye into

a palm-size bouquet and takes it into the house as a good-luck charm for next year's harvest.

Not far along, just as the Wakhan valley widens out at the town of Ishkashim, Nowshak

Peak looms briefly in the distance. At 7492 meters (24,580'), it is Afghanistan's

highest summit. Thus Khuvaydo, like his crops, is well accustomed to the early and

severe cold that comes here. "In winter," he says with a smile, "we just clear away

the snow from our fields and play football."

The Pamir Biological Institute in Khorog includes one of the world's highest botanical

gardens at 2320 meters' elevation (7600'). Among the most striking trees in the garden,

which includes some 2300 total species and varieties of flora from all over the world,

are an impressively weeping Morus alba, or white mulberry, as well as many species

of poplars, especially the Populus nigra, that tall, stately, vertically branched

tree which dominates the Pamiri landscape. The personal favorites of Ogonazar Aknazarov,

director of the Institute, are Betula pamirica, a birch, and Juniperus

shugnanica, a juniper—both local varieties, to judge by their species names

—and of course the beloved Armeniaca vulgaris, or wild apricot.

Professor Aknazarov is the consummate academician, educated in the rigorous Soviet system

at the Komarov Botanical Institute in St. Petersburg. His desk is piled high with books

and dried specimens, and he can cite the Linnaean taxonomy of his rarest accessions with

ease. Yet he is also a soft-hearted nostalgist for the food pleasures of his past. "My

first memory of the family garden," he says, "is stuffing myself with ripe mulberries.

My friends and I would climb the trees and eat until our faces and fingers were black

with juice. We called each other monkeys, although we had never seen a monkey in our

lives. Wheat bread may be the Pamiris' first food, but tut-pikht—mulberry

bread—is our second."

When asked about a line from the Travels of Marco Polo about the Pamirs—

"Good wheat is grown, and also barley without husks. They have no olive oil, but make oil

from sesame, and also from walnuts"—he concurs, remembering how, as a child, he

stole walnuts from his neighbor's trees, and couldn't deny it when he was questioned

because his fingers were stained and sticky with walnut juice. But he notes that Marco

Polo forgot to mention apricot oil, made from the fruit's kernel, which is a cure for

high blood pressure if taken with warm milk. And the "barley without husks"? It is called

naked barley, Hordeum vulgare var. nudum, he agrees, and is common

in the Pamirs.

Aknazarov accompanied American ethnobotanist Gary Paul Nabhan on the tour of the

Pamirs in Vavilov's footsteps that Nabhan recounted in his book Where Our Food

Comes From. The Pamirs, like the Caucasus, are a veritable "mountain of tongues,"

as the Arabs called the latter: Each valley has its own language, all of them from

the Eastern Iranian family, such as Wakhi, Shugni and Ishkashimi.

The professor speaks them all, which caught Nabhan's attention. "The mere act of

naming a newly found variety," he wrote, "leads to isolation and further selection.

Vavilov surmised that at a larger scale—that is, in the Panj River watershed—

linguistic diversity could well have fostered crop diversity." Thus when, say, one

particular apple tree turns out an especially healthy and sweet fruit, and is then

selected for further planting and given a name in that valley's dialect, then that

apple suddenly becomes a new variety of Malus domestica, and will perhaps

gain fame throughout the valley and spread out from there up and down the Pamirs.

|

Plain old cereals and legumes are less likely to gain such fame, or to travel far

afield because of it, and that is why it is so important for collectors of their

seeds to go to those valleys in person. The team from icarda,

vir and New Zealand's Forage Centre will return to Tajikistan's capital of Dushanbe

to clean, sort and divide seeds. One duplicate set will be left at the National

Academy's own seed bank; others will be sent through quarantine to Aleppo, Palmerston

North and St. Petersburg, and eventually to seed banks around the world. And perhaps

that pest-resistant fungal endophyte found in a grass seed at 2800 meters, or that

salt-tolerant gene found in a wheat variety up the Ghunt River valley, may one day

be of use to science. "

But in the meantime, amateur plant collector Parpisho Kimatshoev is not waiting for

foreign scientists to work their slow process of seed collecting and analysis.

Oblivious to the interest that the outside world takes in Pamiri biodiversity, he

goes about his weekly routine, heading to the mountains outside his hometown of

Khorog. Does his neighbor have an upset stomach today? For that he will collect

zirdos, a yellow yarrow flower whose petals he will dry, pulverize and

mix with sugar and water. Are Kimatshoev's 60-year-old bones aching? For that, he

might make a poultice of hichifgorth, which he has seen lame ibex eating.

Does his daughter need to clean her system? For that he will gather nakhchirwokh

root, to boil, cool in a dark place for two days and give her to drink.

Kimatshoev calls his medicinal plants by their Shugni names, which are not found in

any dictionary. He says they grow in places only he knows, and he is not sure he

should show foreigners where to find them. He has nothing against western medicine

or modern agronomic science, he says—it is just that he would rather cure his

ills according to old Pamiri ways, by eating what grows wild in his own mountains.

|

Louis Werner is a freelance writer and filmmaker living in New York. |

|

Istanbul-based photojournalist Matthieu Paley

(www.paleyphoto.com) specializes in documenting

the cultures and lands of the Pamir, Karakoram and Hindukush mountain ranges. |