All my adult life I have collected silver jewelry from the Middle East. It began in 1960,

when I received a grant to spend the summer studying Arabic in Lebanon. From there I visited

Damascus, and I went home with my first bracelet. Later, throughout a 30-year diplomatic career,

I collected jewelry. At first it was just to wear, but as my husband, David, grew as interested

in silver as I, we bought larger and more complex pieces. By 2000 we had accumulated a

significant collection.

|

|

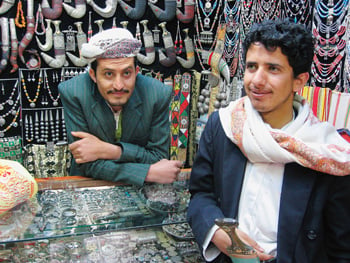

Silversmith Ali Muttahar al-Ma'amari, left, is among the new generation of silversmiths from

al-Rujum, west of Sana'a. At right is his cousin, Walid al-Ma'amari.

|

Through forays to jewelry markets around the Mediterranean and throughout the

Arabian Peninsula, I learned that the most intricate jewelry came from Yemen.

I found good Yemeni pieces in Jiddah, Damascus, Cairo and, on rare occasions,

in the us. As time went on, I focused my attention

more and more on Yemeni silver, not only because of its unsurpassed craftsmanship,

but also because, by the late 1990's, it looked as if this traditional craft

might disappear.

This threat had its roots in the decline of both demand and supply. Gold had

risen in value over the previous few decades, reducing the relative value of

silver, and silver thus became too inexpensive to serve as a depository of family

wealth, as it had for centuries. At the same time, even the idea of keeping wealth

in such a form became old-fashioned as banks became more accessible. For those

families who did retain some wealth in the form of jewelry, gold became the metal

of choice, even if a family could afford only a piece or two. Lifestyles changed,

too: Instead of receiving jewelry as wedding gifts, as was traditional, new couples

often preferred appliances. And of the silversmiths, many of the most skilled had

been Jews, and in the late 1940's and early 1950's, most of Yemen's Jewish

population emigrated to Israel.

In the early 1990's, I began to lecture on Yemeni and Middle Eastern jewelry,

and I arranged the exhibition "Silver Speaks: Traditional Jewelry of the Middle

East" in 2004. After I addressed the Freer Gallery Seminar on Yemeni Culture in

2002, Abdul Karim al-Iryani, then a special advisor to the president of Yemen,

encouraged me to research and write more on Yemeni jewelry. A year and a half

later, thanks to research support from the American Institute for Yemeni Studies,

I was on my way back to Yemen, and between 2005 and 2007, I spent about a year

there.

That is when, to my delight, I found that a new, young generation of

silversmiths had grown up. Despite the difficulties of low demand and, most

recently, political turmoil, they are keeping the traditional craft of finely

worked silver alive. I sought out and spoke with about 40 of them.

In particular, a group or "school" of young men from al-Rujum, north of Sana'a,

had been receiving encouragement from their fathers to learn silversmithing. Silver

was cheap, it seemed, so they could melt down their mistakes and resell the bullion

without major losses. To a person, these young men are proud to be continuing one of

their country's finest artisanal traditions—and willing to face a new, uniquely

21st-century, challenge: Sana'a markets are full of Chinese tin-and-plastic copies

of Yemeni traditional jewelry.

There is, however, a market for their best work in Saudi Arabia. A fine hand-tooled

sword of 85 percent silver might bring as much as $2500; a new woman's belt done in

filigree might bring $1000. (A good antique one might fetch up to $3000.) A few

families in Sana'a have purchased complete new sets of wedding jewelry in the

traditional style. Tourists, when they come, buy the new work, too. But most of the

silversmiths agree that, if these crafts are to thrive again, there will have to be

more customers.

|

Collector, curator and writer Marjorie Ransom (maransom@verizon.net) first showed her collection of traditional Middle Eastern silver jewelry in 2003 in Washington, D.C. It has since appeared in solo and group shows in New York, San Diego and at the Arab American Museum in Dearborn, Michigan. A book, Silver Treasures from the Land of Sheba, has been accepted by the American University in Cairo Press. |