|

|

Appearing as if she might either sing or weep yet again, this statue of Umm Kulthum in

Zamalek, in central Cairo, hints at the emotion and operatic posture for which she

became a legend. Now silent amid the honking swirl of traffic at her feet, it is

perhaps fitting that her back is turned to the tower on the site of her former home,

and her face and hands open toward Egypt's most enduring symbol: the Nile.

|

he visitor to Cairo is never far from the sound of Umm Kulthum, the great

Egyptian singer. Although she died in 1975, her voice is still everywhere.

It's the plaintive, lamenting, yearning voice you hear coming from the

cassette players of taxis, from countertop radios, from the doorways of shops

and cafés. Her music is as much a part of the Cairo streetscape as the warm,

exhaust-laden air and the ubiquitous desert dust that seems to turn everything

in the city an ancient shade of soft, stony brown.

he visitor to Cairo is never far from the sound of Umm Kulthum, the great

Egyptian singer. Although she died in 1975, her voice is still everywhere.

It's the plaintive, lamenting, yearning voice you hear coming from the

cassette players of taxis, from countertop radios, from the doorways of shops

and cafés. Her music is as much a part of the Cairo streetscape as the warm,

exhaust-laden air and the ubiquitous desert dust that seems to turn everything

in the city an ancient shade of soft, stony brown.

For the non-Arab, the music itself has what at first sounds like an impenetrable

strangeness. Nothing about it seems familiar to the western ear. The scales

are different; you can't distinguish major from minor notes; there is no obvious

rhythm; it's hard to tell if you're hearing the beginning, the middle or the end

of a song. Yet it's also obvious that this is highly elaborate, highly formal

music, instrumentally virtuosic and precise, and conveying powerfully intense emotion.

Edward Said, the Palestinian—American intellectual whose early musical education

was based on the western classics, reacted with dismay when, as a boy, he attended a

concert by Umm Kulthum in Cairo in the 1940's. It was "a dreadful experience," he

told a Dutch television interviewer in 2000. "The tone was mournful, melancholic.

I did not understand the words.

"It did not begin until 10 o'clock at night. I was half asleep ... [in] this great

crowded theater," Said went on. "There did not seem to be any order to it. The

musicians would wander on stage, sit down and play a little bit, wander off, and then

come back, and finally she would appear.... And her songs would go on for 40 to 45

minutes. And to me there was not the kind of form or shape [I was used to in western

classical music]: It seemed to be all more or less the same."

Certainly the enduring power, meaning and mystique of Umm Kulthum's art do not

translate easily from the Arabic. The western enthusiast of world music who, in

pursuit of the exotic or the novel, might seek out recordings and performances of

Balinese gamelan music, Indian ragas or African dance music will not instantly find

what he or she is looking for in the vast catalogue of Umm Kulthum's recordings.

Her music's appeal seems distinctly Arab and even specifically Egyptian. Her life

and work weave together an experience of Arab and Egyptian history and sensibility,

and the music must be understood in Arab and Egyptian terms. Umm Kulthum herself,

in her 50-year career, would not have considered for a moment trying to seek a

non-Arab audience.

|

|

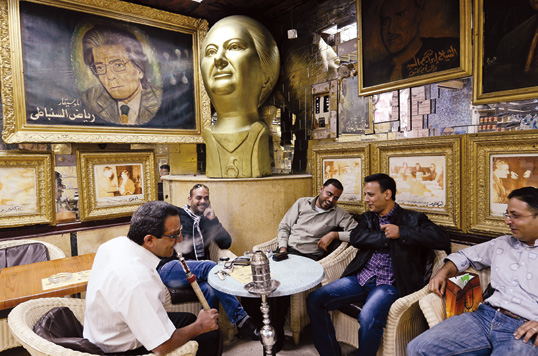

An enormous bust of Umm Kulthum decorates a coffee shop in downtown Cairo where her music,

and much animated conversation, fill the air.

|

This doesn't mean that we can't appreciate her music or learn to love it.

Said's view changed as his studies of western classical music and Arab culture

proceeded, and he came to appreciate qualities that Umm Kulthum's work embodies:

variation, digression and elaboration rather than logical structure; timelessness;

an atmosphere of contemplation; and potentially infinite ornamentation.

Said doesn't say where he heard Umm Kulthum perform that memorable evening. It

could have been in one of several theaters in downtown Cairo. But he certainly

heard her at a good time. By the 1940's, Umm Kulthum was well established as the

dominant figure in Egyptian popular music. At that time, with the country straining

under the pressures of continuing British political dominance, an unpopular monarchy

and economic hardship, she articulated the feelings of the ordinary Egyptian in a

way that no other artist did. And this was only the midpoint of her career. By the

time Said heard her, she had already been performing for a quarter of a century, and

her career still had another quarter-century to run.

|

The singer's evolution from the country girl, born Umm Kulthum Fatima Ibrahim al-Baltaji,

to the national icon known only by her first name took place almost entirely in Cairo

itself, and one can easily make a walking tour of sites in the city's downtown where

important moments of her life took place. To do so now is very much an exercise in

nostalgia. Although many sites can be located, many others no longer exist or have

been transformed beyond recognition in the city's endless process of change.

The original Umm Kulthum was, according to tradition, the daughter of the Prophet

Muhammad and his first wife, Khadija, and later the wife of the Caliph 'Uthman.

The name itself means "the one with (literally, the mother of) the round face."

Born in 1904 (probably) in a village in the Nile Delta, Umm Kulthum began her

career singing religious songs at social gatherings in the Delta countryside,

accompanied by her father, who was an imam, and other relatives. Before she found

Cairo, Cairo found her: Even as a teenager, her reputation was such that she was

soon asked to sing at the homes of prominent Cairo families and in Cairo theaters.

In 1923, to advance her career, she finally made the move from the country to the city.

The center of the city's entertainment business at the time of Umm Kulthum's

arrival was the area in and around the Ezbekiya Gardens, originally a European-style

landscaped park built by Khedive Ismail in the 1870's as part of the celebrations

for the opening of the Suez Canal. Nowadays the Ezbekiya Gardens, in the heart of

downtown Cairo, resemble a vast building site, with little greenery remaining,

overlooked by an elevated highway and surrounded by tall buildings—but in

the 1920's the gardens contained a number of small theaters and music halls.

In such places, accompanied by her small ensemble of family members, Umm Kulthum

sang a mixed repertoire of religious and popular songs. In these often rowdy venues,

her appearance attracted as much attention as her voice. While other popular singers

of the day favored sequins, fancy head-dresses, shape-enhancing gowns and exposed flesh,

Umm Kulthum dressed like a man, in a bulky black coat with a headscarf held in place by

a cord, attire that gave her a distinctly rustic air. As the daughter of a cleric, she

was careful to preserve her physical modesty, and she maintained this sense of propriety

for the rest of her life. It formed her signature look: She was never seen wearing

anything but a long-sleeved dress that reached her feet, with a high neckline.

|

| library of congress |

|

Umm Kulthum gave her name to venues like the Umm Kulthum Alhambra

Theater in Jaffa, Palestine, photographed in 1937.

|

The newspaper Al-Ahram published notices that appeared around Cairo

advertising Umm Kulthum's performances during this period. The Ezbekiya Gardens

Theater announced an evening's "open-air musical performance" featuring "the

famous singer, the Lady of Song, Umm Kulthum. Delight in song beneath the stars.

Women's private section available. General entrance 10 piastres."

In an instance of imitation being the sincerest form of flattery, some unidentified

rival singers—now lost to history—took her name at one point, compelling

Umm Kulthum herself to issue a notice clarifying the matter: "I alone am the original

Umm Kulthum and I am Umm Kulthum Ibrahim al-Baltaji. As for the others, they are false

ummahat [that is, 'Umms'] of Kulthum, whom Kulthum disowns, denying their

relationship to singing."

|

|

It was in the 1930's that Umm Kulthum began to give her radio concerts from Cairo's old

Opera House, which burned down in 1971. The site is now a parking garage on Opera Square.

|

The country girl who arrived in Cairo unable to use a knife and fork soon began an

intensive program of education, self-improvement and self-invention. She studied classical

Arabic poetry and music with masters of these arts. Socially, her ambition took her into

the salons of wealthy and cultured Cairo families, and she adopted the manners and style

of dress of the friends she made among cosmopolitan Cairene women. Three years after

arriving in Cairo, she took the radical step of dropping the ensemble of family members—

including her father and her brothers—who accompanied her in performance. By this time,

she had surpassed them musically, and they were a brake on her career. As one critic noted,

"As for her presentation on stage, the weakness there is our gentlemen 'the shaykhs' who

surround her, sometimes sitting like stone idols, sometimes stirring about. What is the

use of their sitting around her so?"

She replaced them with a classical Arab ensemble that included some of the best musicians

in Cairo. Her first concerts with this new group, at the Dar al-Tamthal al-'Arabi ("The

Arab Theater") in the Ezbekiya area in September 1926, were an outstanding success. "Her

voice has a perfect sound," a critic wrote, "especially after she advanced these new

developments this season." Her talent was accompanied by a keen business sense. Not only

did she establish herself as the country's preeminent singer, but she was also the best

paid, negotiating all deals herself in a steely and imperious style.

One of the sites in Cairo most closely associated with Umm Kulthum's reign over Egyptian

popular music was the old Opera House, a stone's throw from Ezbekiya Gardens. While Opera

Square remains a Cairo landmark, dominated by an equestrian statue of the 19th-century

general Ibrahim Pasha (his arm upraised, pointing the way to victory), the Opera House itself

burned down in 1971 and was replaced by a large, drab parking garage. The Opera House, another

of Khedive Ismail's grands projets, was built 1869 in splendid French style—

mostly of wood, unfortunately—and hosted the premiere of Verdi's opera "Rigoletto." In

the 1930's, it was the setting for Umm Kulthum's earliest radio concerts. These concerts,

which were soon regularly broadcast on the first Thursday of every month, became a central

feature of social and cultural life across the Arab world and are perhaps the most famous

aspect of Umm Kulthum's legacy.

|

|

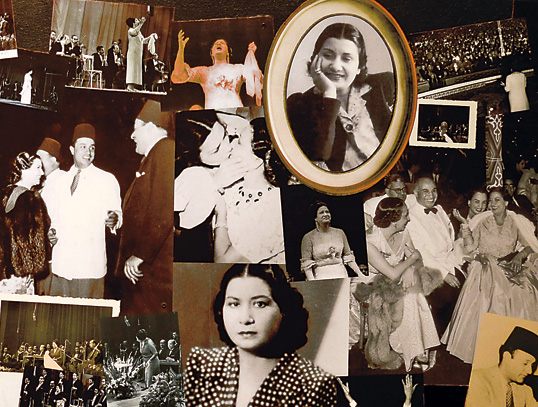

The Umm Kulthum Museum displays a photo collage, above, highlighting The Lady's life and

career, as well as the microphone, below, that she used for her first radio performance.

|

According to legend, the Israeli military command timed its first air attack on Egyptian

forces at the start of the 1967 Six Day War for the night of the Umm Kulthum radio concert,

when it could be sure that the entire Egyptian population would be glued to their radio sets

and distracted from military matters. The legend is false: In fact, the first attack took

place Monday night, June 5, 1967; the second, definitive attack came the following day.

The element of truth in the story is that the Thursday night radio concerts did indeed

clear the streets, and people did indeed gather around their radios to listen. Unlike

today, when listening to the radio is mostly a solitary activity, listeners to the Umm

Kulthum radio concerts formed an extension of the audience in the concert hall. People

listened to the broadcasts in cafés and in groups at home, and ate and drank during the

long intervals between songs. In his novel Miramar, Naguib Mahfouz describes a

group of residents in a Cairo pension gathering together for this collective experience:

The evening of Umm Kulthum's concert is a magnificent occasion, even at the Pension

Miramar; we drink, laugh and talk of many things, including politics. But even strong

drink cannot get the better of fear. [The context is the increasing harshness of the

Nasser revolution in Egypt.] ... The singing starts and they listen greedily to the

wireless. I grow tense. As usual, sure, I can follow a verse or two, but I quickly get

bored and distracted. There they sit, wrapped up in the music, and all I feel is terrible

isolation. I'm astonished that Madame is as fond of Umm Kulthum as any of them. 'I've

listened to her for so many years,' she explains when she observes my surprise.

Tolba Marzuq is listening intently. 'Thank God they didn't confiscate my ears, too,'

he whispers to me.

Umm Kulthum performed these monthly radio concerts for 36 years. The last one was in

1972. By that time, her career had assumed a political dimension. She was chairwoman of

the Listeners' Committee of Egyptian Radio, a position that gave her enormous influence

over the music and musicians chosen for broadcast. She also became head of the national

Musicians' Union. In the aftermath of the Arab defeat in the 1967 Six Day War, she made a

tour of Arab cities to raise money for the depleted Egyptian treasury, traveling on a

diplomatic passport, which gave her arrival in a city the character of a state visit. Her

friendship with President Gamal Nasser was well publicized: He would invite her to his

home to break the fast on the first night of Ramadan, and he showered her with decorations

and awards.

By the late 1960's, her health was declining. Her marathon performances—which at

their peak had typically lasted five or six hours, starting at about 10 p.m. and finishing

around three a.m.—became shorter. She gave her last concert in December 1972 at the

Qasr al-Nil cinema in downtown Cairo, a short distance from the famous Groppi café. The

occasion was a poignant and dramatic ending to her long career. As commentator and longtime

fan Maurice Guindi wrote in Al-Ahram Weekly in 2000:

She started off with Abdel-Wahab's "Laylat Hubb" ("A Night of Love"), giving a sparkling

two-hour rendition with numerous variations of her own that left the audience dazed. Her

second song, a religious one about the holy sites, required a high pitch at many points.

At one of those points, and without advance warning, her voice cracked, sounding a discordant

note. She froze and the orchestra stopped playing. There was dead silence in the hall for a

few seconds followed by frenzied applause from the 1800-strong audience. The outburst seemed

to reflect a mix of love, encouragement, compassion and maybe pity. I was dumbfounded, telling

myself that the slip was just the result of exhaustion after the strenuous effort made in the

first song and that the lady would bounce back.

|

During her final illness, crowds gathered outside her elegant house on Abu al-Fada Street on

the northern tip of Zamalek Island. Regular reports on the state of her health were issued by

newspapers and radio stations throughout the Arab world. She died in a hospital on February 3, 1975.

Her funeral was an extraordinary outpouring of popular feeling. An orderly procession led

by a military band crumbled as the throng of mourners—estimated in the millions

—seized possession of her casket and bore it through the streets of Cairo to the

Sayyid Husayn Mosque, named after the grandson of the Prophet Muhammad. The symbolism

in this was powerful: The initial funeral prayers took place in the 'Umar Makram Mosque

near Tahrir Square, a prestigious downtown mosque where the funerals of famous people

traditionally are held, but the mourners carried the casket nearly five kilometers

(3 mi) away to a place where further, unscheduled prayers were recited. It was as if

the ordinary people of Egypt, among whom Umm Kulthum was born, were reclaiming one of their own.

|

|

|

Top and above: Two of The Lady's signature possessions—her scarf and her

diamond-encrusted glasses—are on display near the museum's entrance.

|

Her body was entombed in the Bassatine Cemetery, in the southernmost part of

the City of the Dead, south of the Citadel. Visiting it is a pleasant excursion.

Once you are through the cemetery gate, an attendant will guide you along a narrow

avenue to the tomb and unlock the heavy steel doors, on receipt of payment. Inside,

the tomb looks like a modest but dignified sitting room, with upright chairs,

tables, arrangements of plastic flowers and framed calligraphic inscriptions on the

cool white walls. "The Lady" (al-Sitt), as Umm Kulthum was called, lies under a

stone slab in the floor.

New monuments to Umm Kulthum have risen in Cairo in recent years. Her house in

Zamalek was demolished with unseemly haste not long after her death, to be replaced

by a hotel and apartment building named after her. In acknowledgment that this was

where she lived, a large statue of her stands nearby, a rare example in the Middle

East of a statue of a woman. But perhaps her best memorial is the Umm Kulthum Museum,

located at the southern tip of Roda Island, in a building that formed part of the

Ottoman Manasterly Palace. Here one can see relics of The Lady herself: jewel-encrusted

sunglasses and dresses, medals she received from governments and organizations across

the Arab world and memorabilia from her performing and recording career.

The old Opera House has been replaced by a new Opera House, in Zamalek, across the

Qasr al-Nil bridge. Here an annual Umm Kulthum memorial concert is held in which young

performers recreate her familiar songs with extraordinary power, feeling and virtuosity.

It is an event that shows that Umm Kulthum's music is still a living part of the culture

of Egypt.

I have an Egyptian neighbor in London. When I told him I was writing about Umm Kulthum,

he stopped dead in the middle of the street, as if the ghost of the singer had suddenly

appeared before him. "I met her, you know," he said, astonished to be summoning up a

long-dormant yet still vivid memory. "She came to a party at my parents' house. I was

very young at the time. I remember this very tall woman, standing all alone, wearing

dark glasses. It was Umm Kulthum! But no one dared to talk to her. She was too famous!

She was a legend, and we were terrified of her!" he said.

|

Edward Fox (www.edwardfox.co.uk)

is the author of Palestine Twilight: The Murder of Albert Glock and Archaeology

of the Holy Land, among other books. He lives in London. Photo courtesy of Caroline

Forbesus. |

|

Dana Smillie is a freelance photographer and video journalist living in Cairo.

|